What makes a town grow into a little city? What makes a little city blossom into a big city? And what makes a big city develop the stature and the atmosphere of a metropolis?

The answer is: Men. Men with vision. Men with courage. Men with “push” and vitality and ideas. Men who dream dreams and are willing to work hard to make those dreams cone true. Most of all, men who have these qualities leavened with a large helping of community spirit.

With those introductory words and using the fact-based gender language of the day, Harold L. Mueller, Daily Oklahoman staff writer began his full-page article in the April 23, 1939, the Daily Oklahoman which commemorated and celebrated the city’s Golden Anniversary, the city’s first 50 years. He wondered out loud …

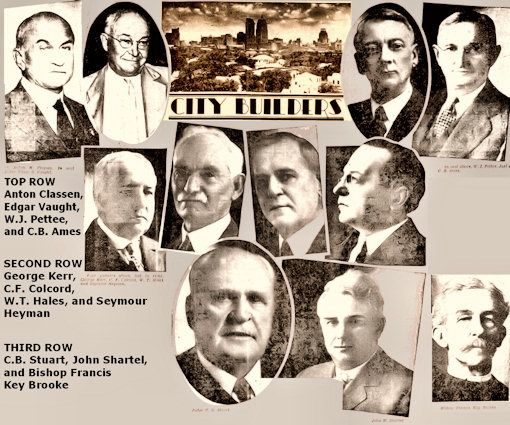

What would Oklahoma City have been without Anton Classen, the developer, the real estate man, the promoter of the street railway system and the interurban lines, and what would it have been without Charles F. Colcord, the builder? What would it have been without such early-day merchants as Sidney Brock, T.P. Mellon, Seymour Heyman and George Kerr? Without Henry Overholser, who launched the opera house and the fair grounds?

Today, we might also wonder out loud, “Who were the men and women during the last 50 years who filled the shoes of the likes of Classen, Colcord, Overholser, and Shartel, and, 52 years after the 1939 article was written, are any such men and women around the city today?” The bold language of 1939 bears repeating today …

- Men and women. Men and women with vision. Men and women with courage. Men and women with “push” and vitality and ideas. Men and women who dream dreams and are willing to work hard to make those dreams cone true. If they are to be found in the town, who are they?

- Most of all, men and women who have these qualities leavened with a large helping of community spirit. Same question but with a twist — are we able to identify any City Builders who have “these qualities leavened with a large helping of community spirit” in Oklahoma City today?

THE 1ST 50 YEARS. First of all, I’ve copied the full page September 23, 1939, article, and you can click on the thumbnail or here to see and/or read it. But the file is quite large (2484 x 3000 px) and it won’t print well at all since, when printed, the words would be much too small to read without a magnifying glass. As a remedy, I’ve parsed the article into four separate files which will read and print much more readily … click on any link below … in these files, the original columns have been reformed into pairs for easier reading and much better printing.

THE 1ST 50 YEARS. First of all, I’ve copied the full page September 23, 1939, article, and you can click on the thumbnail or here to see and/or read it. But the file is quite large (2484 x 3000 px) and it won’t print well at all since, when printed, the words would be much too small to read without a magnifying glass. As a remedy, I’ve parsed the article into four separate files which will read and print much more readily … click on any link below … in these files, the original columns have been reformed into pairs for easier reading and much better printing.

In the article, Mueller reviews the advantages of Oklahoma City’s location, climate, and transportation (rail) facilities and that the city was the agricultural center for shipping and mentions the city’s “other natural resources” which I presume means oil and gas. But, he says,

Yet, with all these advantages, Oklahoma City might have been outstripped handily by its competitors for population and prosperity if it had not been for the group of leaders who worked unremittingly to promote growth and prosperity. These men may be called “the builders of Oklahoma City.” No two minds may agree upon the names that should be included in such a list but everyone will agree that no list short of at least two dozen names would be representative of the city’s builders.

Although he gives what I’ll call honorable mention to a few others (e.g., Joe Huckins, hotel man from Texarkana, and Oscar Lee who he called the “mainspring in the construction of many downtown buildings”) and says that the complete list might be as large as 50, when whittling the list of names down to a handful he gives particular attention to those whom he says all would agree should be included … Anton Classen, Charles F. Colcord, John Shartel, C.G. “Grist Mill” Jones, Henry Overholser, W.T. Hales, and four leading retailers, W.J. Pettee, George Kerr, T.P. Mellon, and Sidney Brock. A few religious leaders (Bishop Francis Key Brooke, Bishop William A. Quayle, and Reverend Henry Alford Porter), men prominent in the legal field (C.B. Ames, C.B. Stuart, Dennis T. Flynn, Judge Samuel W. Hayes, and Judge Edgar H. Vaught), and an important cultural leader Angelo C. Scott also made his short list, however I’ll not get into that part of his list here other than to identify them in this sentence — except for Ames who I’ll briefly mention in Colcord’s description below. Here, my focus is on the “physical” builders of the city, not its legal, moral or intellectual leaders, as important as such groups are in defining the fabric of the city.

Henry Overholser. Often called the “Father of Oklahoma City,” he constructed the Overholser Opera House and can rightly be said to have brought a good bit of culture to the city in its earliest days. The opera house, located immediately west of today’s Colcord Hotel, later became the Orpheum, and, in its last days before being destroyed during the Urban Renewal period, the Warner Theater, home of the city’s first Cinerama theater. He was the principal builder of frame buildings beginning immediately with the 1889 Land Run, and, with C.G. Jones, was instrumental in the establishment of the city as a rail hub during the 1890s-1910s. You can read much more about Henry in this earlier article and in Chapter 9 of Angelo C. Scott’s Story of Oklahoma City and you can tour his 1903 home at 405 NW 15th, now owned by the Oklahoma Historical Society managed by Preservation Oklahoma, Inc.

Henry Overholser. Often called the “Father of Oklahoma City,” he constructed the Overholser Opera House and can rightly be said to have brought a good bit of culture to the city in its earliest days. The opera house, located immediately west of today’s Colcord Hotel, later became the Orpheum, and, in its last days before being destroyed during the Urban Renewal period, the Warner Theater, home of the city’s first Cinerama theater. He was the principal builder of frame buildings beginning immediately with the 1889 Land Run, and, with C.G. Jones, was instrumental in the establishment of the city as a rail hub during the 1890s-1910s. You can read much more about Henry in this earlier article and in Chapter 9 of Angelo C. Scott’s Story of Oklahoma City and you can tour his 1903 home at 405 NW 15th, now owned by the Oklahoma Historical Society managed by Preservation Oklahoma, Inc. Anton Classen. I confess to this fellow being my personal favorite among all who were identified in Mueller’s article. About Classen, he observed,

Anton Classen. I confess to this fellow being my personal favorite among all who were identified in Mueller’s article. About Classen, he observed,

He was one of the early heads of the commercial club here [ed. note: forerunner of the Chamber of Commerce]. He promoted the street fair of 1899. He played a stellar role in the first annual reunion of Roosevelt’s Rough Riders here in 1900; in the decision to build Epworth university here; in bringing the M-K-T railroad to town in 1902; in the expansion of the city from a real estate standpoint; in the paving of the streets; in construction of the street railway system and the interurban lines. His was an active, successful career in which personal fortune and community fortune were inextricably intertwined.

If the legal description of your home is in North Highland Parked, West Highland Parked, Marquette, Cream Ridge, Fay’s, Scott’s University, Bell Vern, Neas, Young’s Englewood, Shartel Boulevard, you live in one of his platted additions to the city, and in all but one of them he planted thousands of trees and cultivated them until they could survive on their own. He was instrumental in bringing Schwartzschild & Sulzberger (S & S) (to become Wilson & Co.) and Morris & Co. (to become Armour & Co.) to the stockyards area of the city in 1908-1910. Together, these packing plants employed 2,400 city residents at a time that the city’s population was around 60,000.

Roy Stewart’s Born Grown says at page 164:

After Classen’s death in [December] 1922, Ed Overholser, president and manager of the Chamber of Commerce, who had been here since eight months after the opening, had this to say about Anton Classen: “It has been my good fortune to know intimately all the real town builders. Through association with my father I came in daily contact with them … I have been in their councils … I have heard them express their visions, hopes and fears … I have seen results of all these things crystalized into the wonderful city that we have … One man took a pencil and figured the area in square miles which this city must have to build upon, in the firm conviction that it would have 100,000 population. My father said that if he lived his allotted time he would see a city of 25,000. When that point was reached he raised the estimate to 40,000. I heard C.C. [C.G.] Jones make the prediction that the figure would be 50,000 in his lifetime. Only Anton Classen believed 100,000 after studying the areas needed for residences and business, and other details. Then he began to purchase surrounding land that, in his judgment, the city would require. His success was due to the absolutely correct vision and working toward that vision.”

Oklahoma City’s population in 1920 was 91,295. Ten years later it reached 185,389. So, in the year he died, 1922, I’m figuring that he got it right on the nose. Click here for the Oklahoman’s article reflecting on his life, and, for more, see Chapter 25 of Angelo C. Scott’s Story of Oklahoma City.

John Shartel. Unlike Anton Classen who by all accounts I’ve read was a mild-mannered and modest sort of fellow, Shartel, Classen’s business partner in the Oklahoma Railway Company, was in many ways Classen’s opposite. In 1901, Shartel founded the Metropolitan Railway Company. In March 1902, Classen, who had purchased another streetcar franchise, surrendered it to Shartel and joined forces with him. Soon, a merger between two entities occurred and, in 1907, the “Oklahoma Railway Company” was born. Although Classen was president and Shartel was vice-president of the company, Shartel was the executive in charge of planning, operations, and management. By 1921, the ORC had grown to encompass 66 miles of city tracks 85 miles of interurban connections, all without public subsidy. Without getting into the merits or demerits of whether ORC had overextended or was managed well or poorly (see Trolleys Part II for that discussion), Shartel was the person most responsible, either way.

John Shartel. Unlike Anton Classen who by all accounts I’ve read was a mild-mannered and modest sort of fellow, Shartel, Classen’s business partner in the Oklahoma Railway Company, was in many ways Classen’s opposite. In 1901, Shartel founded the Metropolitan Railway Company. In March 1902, Classen, who had purchased another streetcar franchise, surrendered it to Shartel and joined forces with him. Soon, a merger between two entities occurred and, in 1907, the “Oklahoma Railway Company” was born. Although Classen was president and Shartel was vice-president of the company, Shartel was the executive in charge of planning, operations, and management. By 1921, the ORC had grown to encompass 66 miles of city tracks 85 miles of interurban connections, all without public subsidy. Without getting into the merits or demerits of whether ORC had overextended or was managed well or poorly (see Trolleys Part II for that discussion), Shartel was the person most responsible, either way.

Angelo Scott said in chapter 25 of The City of Oklahoma City,

Classen was the builder, Shartel was the promoter. A man in that position had to be one of two things: a diplomat or a fighter. He chose to be a fighter. He was almost always up against one hard situation or another, but he only rumpled his hair the harder and went on his way undaunted.

* * *

But, he had a softer dream. He fondled for years the idea of a great city club with noble housing. At last that dream became true, and it was chiefly through his individual efforts. The Oklahoma Club, with its beautiful building and luxurious appointments, is one of the treasures of the town, and is a monument to John W. Shartel. And he had still another side, a yet more attractive one. He was a devoted student of history and had gathered about him one of the best classical and historical libraries in the state. For years prior to his death he had been making researches in connection with the Revolutionary war and the Civil war, and had taken voluminous notes for the purpose of writing two volumes concerning certain personalities of those struggles. It is a great pity that his untimely death prevented the realizing of this ambition.See Chapter 25 of Angelo C. Scott’s Story of Oklahoma City and the April 4, 1926, Oklahoman obituary for more.

Charles F. Colcord. An April 24, 1889, land-runner, Colcord served as Oklahoma City’s first Chief of Police from April 9, 1890, until February 9, 1891, and he continued his law enforcement endeavors as a Deputy U.S. Marshall with Bill Tilghman for a few years. He and other wildcatters succeeded in discovering the Glenn Pool oil field in Tulsa County in 1905, and with his profits constructed the 12-story Colcord Building in 1910, said to be Oklahoma City’s first “skyscraper.” He owned the land upon which Delmar Garden and Wheeler Park would come to be located. With Anton Classen and probably W.T. Hales, he was heavily involved in luring Oklahoma City’s pair of meat-packing companies in 1908-1910, as described above. In addition to the Colcord building, he was instrumental in the construction of the Commerce Exchange building in the late 1920s and the 26-story Biltmore Hotel in 1932. He and C.B. Ames led the successful charge to cause the removal of the Rock Island Railroad tracks which had split downtown along what is now Couch Drive until finally removed in 1930 and, as well, elevate the Santa Fe as it passed by downtown to eliminate numerous grade crossings which inhibited street traffic to and from the warehouse district. Colcord chaired the committee which persuaded the public to pass an $8,800,000 bond issue making that track removal possible and, of course, the track removal led to today’s Civic Center constructed largely with federal funding during the Great Depression. At the time of his death, he was the chief executive officer of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Charles F. Colcord. An April 24, 1889, land-runner, Colcord served as Oklahoma City’s first Chief of Police from April 9, 1890, until February 9, 1891, and he continued his law enforcement endeavors as a Deputy U.S. Marshall with Bill Tilghman for a few years. He and other wildcatters succeeded in discovering the Glenn Pool oil field in Tulsa County in 1905, and with his profits constructed the 12-story Colcord Building in 1910, said to be Oklahoma City’s first “skyscraper.” He owned the land upon which Delmar Garden and Wheeler Park would come to be located. With Anton Classen and probably W.T. Hales, he was heavily involved in luring Oklahoma City’s pair of meat-packing companies in 1908-1910, as described above. In addition to the Colcord building, he was instrumental in the construction of the Commerce Exchange building in the late 1920s and the 26-story Biltmore Hotel in 1932. He and C.B. Ames led the successful charge to cause the removal of the Rock Island Railroad tracks which had split downtown along what is now Couch Drive until finally removed in 1930 and, as well, elevate the Santa Fe as it passed by downtown to eliminate numerous grade crossings which inhibited street traffic to and from the warehouse district. Colcord chaired the committee which persuaded the public to pass an $8,800,000 bond issue making that track removal possible and, of course, the track removal led to today’s Civic Center constructed largely with federal funding during the Great Depression. At the time of his death, he was the chief executive officer of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Also, see C.F. Colcord and His Fine Hotel, this Oklahoma Historical Society article, Luther Hill’s A History of Oklahoma 1908, Vol II, and Chapter 25 of Angelo C. Scott’s Story of Oklahoma City.

C.G. “Grist Mill” Jones. Although his informal name came from his initial business, a milling operation, he is principally known for his establishing and bringing a large part of the commercial rail lines to and from the city. Great if not singular credit is due him for the establishment of the city as the venue for the State Fair of Oklahoma in 1907. His April 1, 1911, Oklahoman obituary article noted that his funeral was the most attended in the city’s history and that businesses, city, state and federal courts, were closed in respect to his passing and contributions to the city. You won’t read his obituary without getting teary-eyed, even if you are a guy. Also, see this Chronicles of Oklahoma article by Dan Perry which discusses his involvement in the establishment of Oklahoma City as the state’s capital city. Chapter 9 of Angelo C. Scott’s Story of Oklahoma City discusses him much more than I will here.

C.G. “Grist Mill” Jones. Although his informal name came from his initial business, a milling operation, he is principally known for his establishing and bringing a large part of the commercial rail lines to and from the city. Great if not singular credit is due him for the establishment of the city as the venue for the State Fair of Oklahoma in 1907. His April 1, 1911, Oklahoman obituary article noted that his funeral was the most attended in the city’s history and that businesses, city, state and federal courts, were closed in respect to his passing and contributions to the city. You won’t read his obituary without getting teary-eyed, even if you are a guy. Also, see this Chronicles of Oklahoma article by Dan Perry which discusses his involvement in the establishment of Oklahoma City as the state’s capital city. Chapter 9 of Angelo C. Scott’s Story of Oklahoma City discusses him much more than I will here. W.T. Hales. Of the persons singled out in Mueller’s article for special status, W.T. Hales is the one I presently know the least about. What I presently know is that he was an early-day millionaire in the city who made his fortune from selling mules and horses, but primarily mules, as indicated in this March 11, 1911, Oklahoman drawing, one of a series which portrayed important men in Oklahoma City’s business community. During World War I, he sold a huge number of mules to British, French, and Belgium interests for use during the “Great War.” I also know that the 12-story State National building was built in 1910 and that in 1915 Hales purchased a half interest in the building according to this August 25, 1915, Oklahoman article. Later, in June 1928, he acquired the remaining half-interest. At some point in this process, the building became known as the “Hales Building,” that name persisting for scores of years until the building was destroyed by the Urban Renewal Authority in the 1970s.

W.T. Hales. Of the persons singled out in Mueller’s article for special status, W.T. Hales is the one I presently know the least about. What I presently know is that he was an early-day millionaire in the city who made his fortune from selling mules and horses, but primarily mules, as indicated in this March 11, 1911, Oklahoman drawing, one of a series which portrayed important men in Oklahoma City’s business community. During World War I, he sold a huge number of mules to British, French, and Belgium interests for use during the “Great War.” I also know that the 12-story State National building was built in 1910 and that in 1915 Hales purchased a half interest in the building according to this August 25, 1915, Oklahoman article. Later, in June 1928, he acquired the remaining half-interest. At some point in this process, the building became known as the “Hales Building,” that name persisting for scores of years until the building was destroyed by the Urban Renewal Authority in the 1970s.

In the most effusive Oklahoman article that I’ve yet to read which extols affluent early-day Oklahoma Citians, this August 26, 1917, article gave detailed description of what it described as being “An Oklahoma City Millionaire’s Mansion.” The residence still exists at 1521 N. Hudson.

I am informed, but cannot yet verify, that he was also instrumental in the development of the Oklahoma City stockyards during 1908-1910. As I learn more than I presently know about his contributions to the city, this section will be amended.

- The Retailers: W.J. Pettee, George Kerr, T.P. Mellon, Seymour Heyman, and Sidney Brock. Until many decades later, downtown was the place to shop and to be entertained, and, of course, suburbia didn’t then exist. Mueller singles out these five for special attention and about them said,

Pettee, known familiarly as “Bill” and “The Daddy of Main street,” came with a wagon of assorted hardware and established what grew into an amazing institution. * * * Genial George Kerr — large, blue-eyed and rotund — had an unusual charge of energy and initiative. He had faith in the future of Oklahoma City and he enlarged and expanded his highly-successful department store to keep it ahead of the rapidly-growing city. As he built larger and larger he was convinced the city was headed straight for metropolitan proportions. The population figures of today are testimony of his ability as a prophet.

Pettee, known familiarly as “Bill” and “The Daddy of Main street,” came with a wagon of assorted hardware and established what grew into an amazing institution. * * * Genial George Kerr — large, blue-eyed and rotund — had an unusual charge of energy and initiative. He had faith in the future of Oklahoma City and he enlarged and expanded his highly-successful department store to keep it ahead of the rapidly-growing city. As he built larger and larger he was convinced the city was headed straight for metropolitan proportions. The population figures of today are testimony of his ability as a prophet. While Kerr was building a department store into an institution there was another progressive merchant down the street who divided his energies between making a success of his business and contribution to the community development. That was Seymour Heyman, the pioneer in the men’s store field. Heyman was not only a practical business man but he was an idealist as well. It was he who carried the main responsibility of setting up the city’s first social agencies. A man of engaging personality, he was a prime mover in nearly every movement of a philanthropic nature in the early days.

While Kerr was building a department store into an institution there was another progressive merchant down the street who divided his energies between making a success of his business and contribution to the community development. That was Seymour Heyman, the pioneer in the men’s store field. Heyman was not only a practical business man but he was an idealist as well. It was he who carried the main responsibility of setting up the city’s first social agencies. A man of engaging personality, he was a prime mover in nearly every movement of a philanthropic nature in the early days.In this group of important merchants was the slender, gray T.P. Mellon — a man of influence and acumen who built what many have described as the most important department store of the day. Mellon was neither the expansive type of Kerr nor quite the idealist that Heyman was but he contributed greatly to the progress of the city. In the hears he headed the Mellon store he gained the reputation of being the most enterprising drygoods merchant in the new city where competition was keen. In its later years, Mellon’s would become the home of Rothschild’s which many still remember today. It, too, was a casualty of the Urban Renewal Authority in the 1970s.

Sidney Brock was another of the department store successes. His store was on Main street where Brown’s now is located. He was a quiet man, well-poised and popular. Through all the years he was in Oklahoma City he gave generously of his time to promote the cultural advancement and the material development of the city. One of his outstanding community services was as chairman of the committee that brought the packing plants to the city.

Sidney Brock was another of the department store successes. His store was on Main street where Brown’s now is located. He was a quiet man, well-poised and popular. Through all the years he was in Oklahoma City he gave generously of his time to promote the cultural advancement and the material development of the city. One of his outstanding community services was as chairman of the committee that brought the packing plants to the city.

Also, see Chapter 25 of Angelo C. Scott’s Story of Oklahoma City.

Of these pioneer retailers, only Kerr’s, Mellon’s (later Rothschild’s), and Brock’s (as John A. Brown’s) would survive into the next 50 year period. For more about Brock’s pre-Brown’s period, see see this section in my John A. Brown’s article.

How good a basic list of “city builders” did Harold L. Mueller provide in his 1939 article? I see it as being good enough for a start, but not good enough for a finish. Mueller’s article appears to have tracked the content of Angelo Scott’s 1939 book, The Story of Oklahoma City but Scott’s book doesn’t discuss those responsible for the pair of 33-story skyscrapers which were completed in 1931, and it is hard to imagine that a history of the 1st 50 years would be complete without credit to those responsible for that pair of preeminent Oklahoma City buildings. Neither does his article make reference to the “Quiet Builder,” M.J. Reinhart, who built a bevy of downtown buildings and churches in the city, many of which still exist today, nor Bill Skirvin who built the Skirvin and Skirvin Tower hotels. Consequently, I’ll add this addendum to round out Mueller’s article in a way that I think that it should have been written.

- Frank & Hugh Johnson. These brothers were largely responsible for the construction of the 33-story First National Bank Building during 1930-1931. In addition to establishing the icon by which the city would be known for decades to come, if not even today, Frank Johnson was responsible for numerous cultural contributions to the city during his lifetime and I’ll enumerate several examples before this article is done.

- W.R. Ramsey. Oilman W.R. Ramsey constructed the 33-story Ramsey Tower during 1930-1931. Oklahoman reports indicate that he was largely responsible for the successful completion of the the 11-story YWCA building in 1931. He was nominated for “Most Useful Citizen” in 1930 and 1931, but won neither award. Later, he apparently fell upon hard times and lost his fortune, but that fact doesn’t disqualify him from matching the definition of “city builder” that Mueller stated at the outset of his article. Many years later, another such person, another “city builder,” Neal Horton, would suffer a similar fate, but none would strip that title from either because of their respective economic failures.

Synopsis. In Chapter 28 of his Story of Oklahoma City, published in 1939, Angelo C. Scott offered the following summary of his impressions of the city’s builders:

BOOMS make cities, but men make booms, therefore men make cities. What shall be said of the men who have made Oklahoma City? What possible tribute can be too great for them? I am not expert in the lore of cities and do not know what manner of men have builded other cities. But I cannot conceive that any other city has ever had, at every stage of its progress, more able, more devoted, more self-sacrificing, indefatigable, and unconquerable men to push it on to triumph over every difficulty than Oklahoma City has had and has today.

In the Great War it was remarked that our soldiers didn’t know when to retreat. The enemy said that they didn’t retreat even when they ought to have retreated, and they couldn’t understand that. The men of Oklahoma City have never known when to retreat. They haven’t given a single inch. They have fought as one man, shoulder to shoulder, year after year, decade by decade, through sunshine, storm, and near disaster. And they have conquered! Shell we not all salute them!

And I am including now the leaders and the builders of today. They are not facing the uncertainties of that early period, but they are facing problems vastly more complex. Every honor we so gratefully bestow upon the leaders of that earlier time belongs with equal right to the numerous great leaders of today.

As will be evident by the end of the 2nd 50 year period, he could not possibly have foreseen the complexity that was yet to come.

THE 2ND 50 YEARS. Although the 2nd 50 years 1939-1989) of the city’s (at least, downtown’s) growth, it is possible in retrospect to see at least a handful of people standing in the mold of the early-day city builders. The Great Depression finally visited Oklahoma City in mid-1931 or so. Followed by a period of slow recovery, World War II (1941-1945) focused the nation’s attention on Germany and Japan and winning the war. After that, the city was content to enjoy the peace and perhaps presumed prosperity notwithstanding that suburban shopping and entertainment malls began to emerge in the late 1940s.

By the mid-1950s, downtown had begun to suffer and the need for leadership became increasingly acute. Although I may quite possibly have missed it, I am unaware of any Charles Colcords or Anton Classens during the twenty-year period of time between 1939 and 1959, with the possible exception of Della Duncan Brown, widow of John A. Brown who died on January 25, 1940. During the 1940s and through her own death in 1967, she remained steadfast in her commitment to downtown and during her reign as Brown’s president or whatever her title was, Brown’s substantially expanded to become the singularly premier shopping experience for all of Oklahoma City. After her death, though, Dayton Hudson, and later still, Dillards, successively acquired the pieces of Brown’s which became forever lost as an Oklahoma City retail institution, and none other of her stature would emerge to take her place.

A Changing of the Guard: Individual Capitalists to Public Officials. Aside from Della Duncan Brown who spanned both the 1st and 2nd 50-year periods, with few exceptions, no Anton Classens or Charles Colcords would emerge after the 1st 50 years — their time was done and there would be no more free-wheeling individuals willing to bankroll their accumulated fortunes into risk-ventures in downtown after that 1st 50-year historic period of time, save one. But there would be one notable exception, Neal Horton, and there would be a few others who took no risks other than to their reputations, e.g., Dean A. McGee — without risking his fortune he would nonetheless provide individual leadership in shaping the downtown we know today, and Jack T. Conn, former president of Fidelity Bank and for whom the underground “Conncourse” came to be named. Before that discussion occurs, part of the “new complexity” foretold by Angelo Scott, which he could not have imagined, needs discussion.

The Beginnings of Urban Renewal. In 1954 the federal government adopted the federal housing act, one feature of which was the federal government funding urban renewal throughout the country. A February 27, 1955, Oklahoman article described the basics:

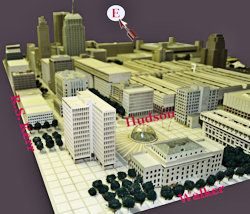

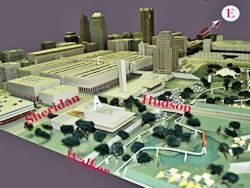

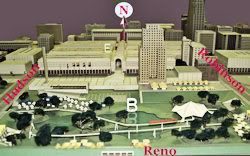

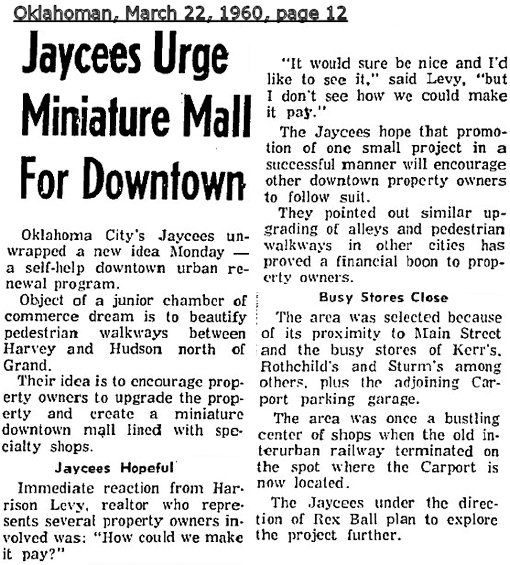

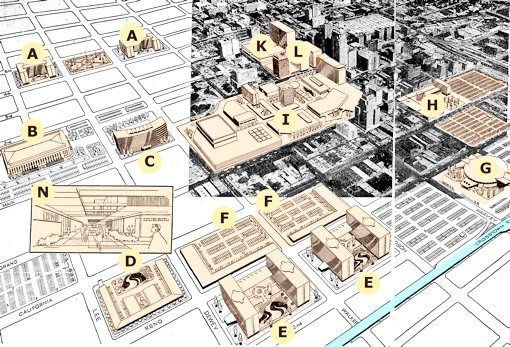

Without going through the legal machinations, getting a statute passed which passed state constitutional muster took more than a few years to accomplish and that hadn’t happened by the 1959 mayoral race. Before the election, the City Council had already gone on record as favoring urban renewal and it doesn’t appear from my review of the Oklahoman’s archives that the issue was even mentioned by 9 of the 10 mayoral candidates, the exception being Everett Curtis whose campaign was staunchly against it. In Oklahoma City, 2nd Time Around Steve Lackmeyer and Jack Money reported that James Norick was a supporter of urban renewal but the topic does not appear to have been a campaign issue by any contestant other than Curtis. In the primary election, the top three vote-getters were Charles Burba (9,807), Merton Bulla (9,587), and James Norick (9,506). Curtis was well down the list with only 925 votes. Norick asked for a recount and, by a 1 vote margin, he became the second-place candidate. In the runoff election against Burba, Norick ran away with a 58,648 to 35,682 vote win (total votes cast was unusually high because also on the ballot was repeal of Oklahoma’s prohibition laws). In the meantime, a bill pending in the Oklahoma Legislature which would authorize Oklahoma City and Tulsa to participate in the federal urban renewal program drew heated opposition, evidenced by the March 1, 1959, ad below (click the ad for a larger view):  Although the bill did pass and was signed into law by Gov. J. Howard Edmondson, legal constitutional challenges would still take more time for resolution. But, what did “urban renewal” really mean? It might mean something simple like what the Jaycee’s proposed in 1960 outside of participation in the federal program.  Privatization of urban renewal, according to Harrison Levy, above, was not very sexy — “It would sure be nice and I’d like to see it,” said Levy, “but I don’t see how we could make it pay.” Statements like that didn’t bode well for the private sector stepping up to the plate and were certainly not reminiscent of the likes of risk-takers Shartel or Colcord. Others during this ambiguous period had more ambitious concepts in mind, such as the concept model put together in September 1959 (click the image for a much larger view as well as the article’s text). Here’s the Legend: A (new apartment buildings); B (expanded Civic Center Music Hall); C (new luxury hotel); D (a motel); E (luxury apartment houses); F (new retail service center); G (all purpose center); H (transportation center); I (mall type central retail area); K (merchandise mart); L (new office building; N (ground level view of one way of building a mall); there is no J or M.  Part of the article’s text reads,

Urban Renewal Comes Slowly. After Gov. Edmondson signed the bill authorizing Oklahoma City and Tulsa to establish urban renewal authorities, the Attorney General issued an opinion declaring the statute unconstitutional; however, in May 1960 he reversed his position and that gave those cities green lights to proceed in accordance with the state statute. But, the Federal Housing and Home Finance agency informed city government officials later that month that the agency would not advance funds until the Attorney General’s position was vindicated by the Oklahoma Supreme Court and that didn’t occur until a December 1966 Supreme Court decision in Isaacs v. Oklahoma City. The Mayor and City Council took some action after the Attorney General’s opinion. In June 1961, the council authorized mayor the to appoint a 5-member Urban Renewal Commission, subject to its approval. In November, Mayor Norick’s list of nominees was blocked “indefinitely” by the motion of council member William C. Kessler, council member who was serving as vice-mayor. Norick then took a trip to Florida, and in his absence Kessler called a council meeting. A November 2 article reported that Kessler said had no plans to submit a list of nominees in the mayor’s absence, but he did — liar, liar, pants on fire. See these three Oklahoman articles. During Mayor Norick’s absence, at a specially called council meeting for November 2, the day after Norick left town, the Oklahoman reported on November 3 that, “The council, taking advantage of Mayor Norick’s absence from the city, pushed through appointment of the five authority members in a move that was forecast shortly before the mayor’s departure for Florida as a guest of the air force. * * * The resolution will be authority for the Urban Renewal board to apply to the federal government for a planning advance. When these funds are received from the federal agency, the board could set up for business.” Norick, of course, was not impressed, and who would be with Kessler’s deceit and treachery and those members of the council that were complicit in the November 2 special meeting. (Kessler would later be appointed the Oklahoma County Associate District Judge.) A July 22, 1962, Oklahoman article reported that the Urban Renewal Authority asked the City Council to select Oklahoma City’s first urban renewal project area, which would place it in position to make an application for federal funds for use in actual planning on a particular project. I didn’t look closely enough to determine the outcome of that request. In the meantime, a private group, Urban Action Foundation, was formed. An August 17, 1962, Oklahoman article reported that, “Creation of a park area in the heart of downtown along the lines of Copenhagen’s famed Tivoli Garden is being planned by the newly-formed Urban Action Foundation. Those making the trip were Dean McGee, chairman of the group, and Stanley Draper, Edward L. Gaylord, Harvey Everest, and Frank Hightower.” This group was the most significant of any other private endeavors in what would eventually lead to the city’s Urban Renewal Plan, as will become clear. On November 6, 1962, the City Council approved the identification of the areas which would be involved in the city’s urban renewal plan: (1)University Medical Center — NE 13th on the north to Rock Island Railroad on the south; Lottie on the east and Lincoln Boulevard on the west; (2) South Central Area — Main Street on the north, Oklahoma City (North Canadian) floodway on the south; Santa Fe Railroad on the east and Western Avenue on the west; (3) Reno-May Area — South of Reno and east of May in the George Washington Carver School and Doffings Addtion; and (4) Pocket Renewal Areas — “A series of seven ‘remnant’ areas bypassed by the city’s growth” were also included. |

| The Pei Plan. Time passes. The next activity of real significance that I could find was this June 21, 1964, Oklahoman article which is the earliest that I could locate which named I.M. Pei. There may have been earlier articles, but the Oklahoman’s search feature for 1963 and 1964 appears to be broken. The article notes that the Urban Renewal Authority had contracted with the previously mentioned Urban Action Foundation, “a citizens group under which the foundation will guarantee funds for preliminary preparation of the project. Funds will go for consultants and staff work on the General Neighborhood Renewal Plan, which was unvelied June 9 by I.M. Pei, planning consultant for the project.” By the time of the article I.M. Pei and Associates had been advanced $125,000, which the article described as “the full cost,” but the number would grow. In Chapter 2 of Oklahoma City, 2nd Time AroundSteve Lackmeyer and Jack money said that, “The Urban Action Foundation paid $200,000 to Pei and his partners to come up with a plan that would make Oklahoma City a leader in urban renewal.” The Oklahoman article noted that, after the plan would be approved by the city planning commission and the City Council, the city would then be in a position to request that the federal agency reimburse such advances by the Urban Action Foundation.

If you’re thinking that $200,000 doesn’t sound like a lot of money for a project as vast as most of you already know was, according to The Inflation Calculator, 1964’s $200,000 would be $1,368,642.86 in 2009 dollars. In December 1964, the great unveiling would occur. Pei had been invited to describe it at a city planning commission meeting on December 10, but when he saw that the meeting was open to the public, he and his group quickly conferred and decided not to attend. The December 11 article describing this turn of events does not explain why, but perhaps they were simply wanting to save the public unveiling at the Chamber of Commerce luncheon in the Skirvin’s Persian room the next day. That unveiling was described in the December 12 article by Jim Reid.

A few of the many views presented in this huge model appear below … click on any image for a larger and much more impressive view. On the same day as the unveiling, Pei also met with a group of 40 architects, and he told them,

If speed was the name of the game, it didn’t happen. Not until December 20, 1966, two full years later, was the downtown element of the city’s urban renewal plan, part 1-A, adopted by the City Council, and not until December 1967 were federal funds received. These Oklahoman articles and their headlines trace the some of the high points:

For much more about the Urban Renewal period, see OKC: 2nd Time Around by Steve Lackmeyer & Jack Money (Full Circle Press 2006), particularly chapters 2-4, More on the Pei Plan: The Power Brokers by Jack Money at OkcHistory.com, and IMPeiOkc.com. |

… incomplete and developing …

1989 AND BEYOND. … this section will be developed after the above is done … might it consider the implications of the SandRidge proposal now pending before the Board of Adjustment …