Later posts in this series: Cops & Robbers 2 – Bill Tilghman

| Primary Sources | Territorial Background | Boomers & Sooners |

| The Land Run | ||

Oklahoma City was “officially” born with the April 22, 1889, Land Run. Were those days as “pastoral” as the painting, “Oklahoma City – April 29, 1889 – Seven Days After The Land Run of 1889,” by artist Wayne Cooper of Depew, Oklahoma? It is permanently displayed in the lobby of the House of Representatives …

Hardly!

This image of the 1889 Post Office, with a man outside standing guard with his rifle, is more likely closer to the truth … I mean, why the rifle?

By the time this post is done, my intention is that this post give a good sampling of the “good guys” and the “bad guys”, i.e., the “cops” and the “robbers” (broadly defined to include claim jumpers, bootleggers, vice, killers, robbers, kidnappers, etc.) from Land Run days through the Murrah Bombing in 1995. This post is in its beginning stage and it will take several days, perhaps more, to complete.

MY PRIMARY SOURCES. I’ll begin by identifying the primary sources even though others may be added as the post develops. Secondary sources will be more particularly mentioned within subtopic items.

(1) 1st Year: 1890 Letter From The Secretary of War. The United States Army was charged with keeping the peace and good order during the Land Run days. The United States Senate adopted a Resolution,

Resolved: That the Secretary of War be directed to transmit to the Senate copies of the various reports of military officers in relation to the affairs at Guthrie and Oklahoma City, Ind.T., from the opening to settlement of said Territory.

Such documents were transmitted by the Secretary of War on February 25, 1890, and were ordered to be printed. Each of the 61 pages of that report is located at here but those pages which pertain to Oklahoma City directly are pages 14-54. Other pages in the full report cover events at El Reno, Kingfisher, and Guthrie. For Okc purposes, I’ve reduced the size of the scans from that original source for quicker loading and printing here. The “Cover” of those reports appears below.

From what I’m able to tell, this report presents the most reliable picture of “Cops & Robbers” that we have during the 1st 10 months or so of Oklahoma City’s history. In this post, I’ll usually refer to this source as Report To Secretary of War with an associated page number.

(2) OCPD History Website. The Oklahoma City Police Department has a nice collection of posts summarizing a good bit of information which begin here (there, in the left margin, select “OCPD History”), but, as a fairly simple survey, it doesn’t develop topics very particularly. Still, it’s useful as an overview. The following time periods are covered: 1889-1910; 1910-1930; 1930-1950; 1950-1970; 1970-1990; and 1990-present. When I refer to this data here, I’ll call it OCPD Internet Source as a rule.

(3) Oklahoma Justice: The Oklahoma City Police, A Century of Gunfighters, Gangsters and Terrorists by Ron Owens (Turner Publishing Company 1995). The book cover looks like this:

This fascinating 1995 book traces the history of the OCPD from territorial days through the Murrah Bombing. In my review of this book at Amazon.com, I substantially said:

An Anecdotal History of the OCPD

While it would be a stretch to regard Ron Owens’ book as a “serious” history book (for example, while it does contain a bibliography, it contains no footnotes citing to references, and, from one interested in research, no index). That said, and while it would be tough to “test” the author’s factual renderings from time to time as a researcher might want to do, it is obvious that the writer has spent countless hours in researching the history of the OCPD from territorial days through the Murrah Bombing, and/or/but, perhaps best of all, he doesn’t “sound like” an academician – the phrasing is straightforward, very readable and pleasurable as he takes the reader through 100+ years of OCPD history, often with a tongue-in-cheek flair.

To illustrate what I mean, at page 12 a description of a gent named “Rip Rowser Bill” appears. He is described as “an armed drunk” who announced his summer 1889 arrival in Oklahoma City with the prophesy, “My name is Rip Rowser Bill and I’ve come to Oklahoma City to start a graveyard.” For many days, he swaggered around menacingly, hand near his gun, repeating his prophesy. Eventually, a local group called the “Knights of the Cottonwood” had enough after Mr. Bill shot a few holes in a tent some of its members were occupying. According to Owens, they “decided that the man’s manners better suited him for residence in Texas,” they tied him up and planned to put him on the midnight trip to Texas. As it happened, and accompanied by “some local officers”, they learned that the midnight train was going to be 3 hours late. The “local officers” exited the scene, “deciding that the intervening time could be better spent elsewhere”, and Rip Rowser was left at the depot under the refuge of the Cottonwood group, all sitting under a cottonwood tree with Mr. Bill. “When the officers returned at the appointed time to load him on the train, they found Bill swinging from a limb of the cottonwood. Locating and questing the committee members, they contended they had left Bill secured to a limb of the cottonwood tree and had limited his wanderings by means of a rope around his neck. A rapidly assembled jury agreed with the men’s contention that the rope had shrunk during the night’s dampness, raising Bill off the ground and causing his death. The next morning, Bill was buried on the banks of the North Canadian River just south of the Military Reserve section now known as the Bricktown area. Thus he fulfilled his prophesy about ‘starting a graveyard in Oklahoma City.’ But not before he was fined $3.30, the amount found in his pockets, for carrying a concealed weapon.”

Sources? None cited. A great read? For sure. All 336 pages may not be as entertaining, particularly when the closer-to-home Murrah Bombing is discussed, but it’s a fascinating and engaging story through and through about the OCPD, and I highly recommend it.

Other “primary” sources may emerge as this post develops, but those are they for the time being. I’ll refer to this source as Oklahoma Justice with a page number reference.

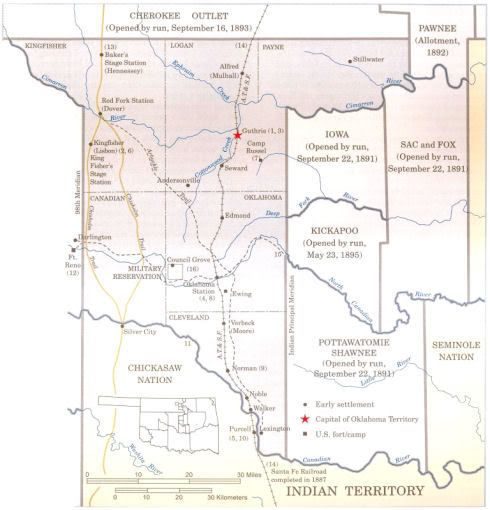

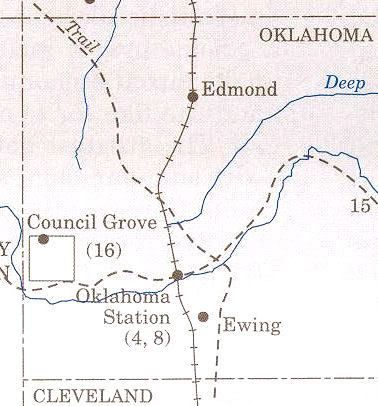

THE TERRITORIAL BACKDROP. What is now Oklahoma County was once part of the “Unassigned Lands ” – i.e., that part of Oklahoma Territory which had not already been assigned to “someone else” prior to the April 22, 1889, Land Run, the “someone else” being a particular Indian Tribe. Whether by design or not, a “cutout” area in central Oklahoma had not been “assigned” to any tribe. This area consisted of what would become some parts or all of these counties: Oklahoma, Cleveland, Payne, Logan, Canadian, and Kingfisher counties. Charles Robert Goins and Danney Gobles’ Historical Atlas of Oklahoma, 4th Ed (University of Oklahoma Press 2006) shows the region at page 125 … click the pic for a larger view …

A Cutout of Only Oklahoma County

The article by John R. Lovett at page 124 says that, “in excess of fifty thousand people are estimated to have participated in this historic event” and says that the Homestead Act of 1862 required that settlers not enter or occupy the land prior to April 22, 1889. The article says, “Tens of thousands of them gathered along the borders of the run area as they awaited the official signal to stake their claims. * * * At noon on April 22, bugles sounded and soldiers fired their carbines and pistols to signal the start of the great land run.”

Other sources indicate the event itself was preceded by several years of national press, perhaps hyperbole, about the upcoming possibilities. See Roy P. Stewart, Born Grown (Metro Press 1974), pp. 1-2. Newspaper stories abounded in such places as the New York World, Chicago Times, Kansas City Times, and the Cincinnati Commercial.

BOOMERS & SOONERS – THE 1st ROBBERS. Well, maybe not the first, but these different groups are the first that I’ll mention here.

Pages 3-5 of Born Grown describe Kansan David Payne’s “Boomer” movement and his movement’s 5-year premature forays into the Unassigned Lands, including Oklahoma County, and, of course, his namesake Payne County. Born Grown says that his favorite cry was, “And the Lord commanded unto Moses, ‘Go forth and possess the Promised Land.'”. In April 1880 Payne attempted to settle an area in what would become Oklahoma City on the south bank of the North Canadian River in a town he named, “Ewing.” See the Oklahoma County cutout, above.

Pages 3-5 of Born Grown describe Kansan David Payne’s “Boomer” movement and his movement’s 5-year premature forays into the Unassigned Lands, including Oklahoma County, and, of course, his namesake Payne County. Born Grown says that his favorite cry was, “And the Lord commanded unto Moses, ‘Go forth and possess the Promised Land.'”. In April 1880 Payne attempted to settle an area in what would become Oklahoma City on the south bank of the North Canadian River in a town he named, “Ewing.” See the Oklahoma County cutout, above.

After Payne’s death in 1884, one of his lieutenants, William L. Couch, became the group’s leader. Although there are more stories associated with the movement’s attempts to colonize Payne County, at least twice, in April 1880 (above) and again in November 1885, the group did the same in Oklahoma County in the “Council Grove” area along the Oklahoma/Canadian county line but troops from Ft. Reno put a stop to that. The area is identified in the Oklahoma County cutout, above. For more about “the Boomers,” see this article and this one at www.okhistory.org, and this article from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

After Payne’s death in 1884, one of his lieutenants, William L. Couch, became the group’s leader. Although there are more stories associated with the movement’s attempts to colonize Payne County, at least twice, in April 1880 (above) and again in November 1885, the group did the same in Oklahoma County in the “Council Grove” area along the Oklahoma/Canadian county line but troops from Ft. Reno put a stop to that. The area is identified in the Oklahoma County cutout, above. For more about “the Boomers,” see this article and this one at www.okhistory.org, and this article from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

Larry Johnson’s good artice at the Oklahoma City Metropolitan Library System identifies other adventures into Oklahoma County by the Boomers. For a time, the federal authories in place were the 9th & 10th Cavalry units, “Buffalo Soldiers.” A snippet from his article reads,

In 1880 settlers from Kansas, known as Boomers because they loudly pushed for opening, attempted to settle in Oklahoma land. Led by David L. Payne and William Couch, the Boomers arrived at land near what is now west of Trosper Park and tried to begin farming, but they were arrested by soldiers from Fort Reno and sent back to Kansas. They made many more attempts to settle: once near what is now Stiles Park; once they laid out a townsite called Ewing (Ewing Cemetery is still on Northeast 63rd Street); and they even tried to settle near Council Grove in 1885 and killed some of Montford Johnson´s hogs and cows! Each time they were run out of “Oklahoma City” by the 9th and 10th Cavalry (Buffalo Soldiers) from Fort Reno.

“Buffalo soldiers” were Black American US Army units authorized by 1866 federal legislation. According to the Medal of Honor website,

The nickname “Buffalo Soldiers” was originally given to the 10th Cavalry by Cheyenne warriors out of respect for their fierce fighting in 1867. The Native American term used was actually “Wild Buffaloes”, which was translated to “Buffalo Soldiers.” In time, all African American Soldiers became known as “Buffalo Soldiers.” Despite second-class treatment these soldiers made up first-rate regiments of the highest caliber and had the lowest desertion rate in the Army.

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, these units were consistently assigned to the harshest and most desolate posts. They were sent to subdue Mexican revolutionaries, outlaws, comancheros, rustlers, and hostile Native Americans; to explore and map the Southwest; to string telegraph lines; and to establish frontier outposts around which future towns and cities grew.

So, the “Cops” were partly Buffalo Soldiers stationed at Fort Reno …

Book Cover of Buffalo Soldiers by William H. Leckie (University of Oklahoma Press 1967)

Click the image to see Amazon’s description of the book

There Were Other Cops, Too – Here the 5th Cavalry, Troop C, Circa 1888

Credit: National Archives

The “Boomers” are not to be confused with the “Sooners.” Three days prior to the land run, it was possible for people to venture into an area to reconnoiter and get their compass bearings to help them identify where to place themselves on an area’s border prior to the Run. Some apparently did not “come back” after making their study but hid out until on or after 12 noon on April 22. Others slipped in by the cloak of darkness without any pretence. Hence, these people arrived “sooner” than they ought and they were not highly regarded by those who “played by the rules.” For more about “the Sooners”, click here. That article notes,

Sooner is the name first applied about six months after the Land Run of 1889 to people who entered the Oklahoma District (Unassigned Lands) before the designated time. The term derived from a section in the Indian Appropriation Act of March 2, 1889, which became known as the “sooner clause.” It stated that no person should be permitted to enter upon and occupy the land before the time designated in the president’s opening proclamation and that anyone who violated the provision would be denied a right to the land.

Were the “Boomers” and “Sooners” “robbers?” Oh, yeah! One would have no trouble making a case for that. But Payne had a county named after him and Couch became Oklahoma City’s first mayor! The University of Oklahoma adopted the name “Sooners” and fans sing about both Boomers & Sooners at football games, for god’s sake! Oh … not to mention, the whole state is known as “The Sooner State!” Well, the white man did rob it from the Native Americans, didn’t he?

THE LAND RUN – GUESS WHO’S COMING TO DINNER? The areas to be invaded were not then laid out in counties and there were no elected or otherwise appointed officials, no police, no courts (other than the distant Judge Isaac Parker at Fort Smith, Arkansas), no laws, no government at all other than the umbrella of the United States Army. While civilian governments got established and organized, the US Army was charged with keeping the peace, assisting local authorities, preventing disorder and preserving the status of “peaceably” established by actual settlers. I think the latter phrase meant that, if a settler’s property claim had been “peaceably” established and others tried to oust them from their property, that would be a “non-peaceable” possession!

The above background snippet intends to set the stage for the April 22, 1889, Land Run. Born Grown, p. 7, identifies those where eligible to make the Run: (a) those who observed the restraining lines, and (b) male citizens 21 years of age or greater, or (c) unmarried, legally divorced or widowed women of the same age, or (d) aliens who declared their intent to become citizens of the United States.

So, at high noon on April 22, 1889, who came? Just the “good guys”? Or, were a bunch more like “Rip Rowser Bill,” described above?

From what I’ve read so far, the words, “raucous,” “raunchy”, and “rowdy” probably give an accurate description of a fair slice of the population in the Unassigned Lands. At page 15, Report To Secretary of War, Brigadier-General W. Merritt wrote …

The military authorities have a difficult task to perform in the management of affairs in Oklahoma, and nowhere is it more difficult than in the town of Oklahoma City. In addition to the good and law-abiding citizens a great many of the worst elements of the population of the Indian Territory, northern Texas, and other Southern States have concentrated in this locality. These in attempting to ply their vocations – gambling and contraband dealing – have been antagonized by the military and are defiant in their abuse of the officers.