May 4, 2009, note: Deep Deuce history is considerably expanded in a 2009 series of 30-40 articles contained in The Ultimate Deep Deuce Collection.

This is the 3rd part of a 3-part series on Oklahoma City’s Deep Deuce. This part focuses on famous Deep Deuce people – see Part 1 for some explanation as to why Deep Deuce even existed in the 1st place, and Part 2 for Deep Deuce History. Since this post is becoming rather lengthy, I’ve added some navigation links to help with movement, below, and within a subtopic click the topic name to move to the next of the subtopics listed below:

Deep Deuce People Background Zelia Breaux Oklahoma City Blue Devils Charlie Christian Jimmy Rushing Ralph Waldo Ellison Internet Resources

Most often, the contemporary focus of Deep Deuce people focuses on the people, mainly great jazz musicians, that sprang from this small part of Oklahoma City’s geography and who came to receive national fame. This post will not be very different even though it should be noted that many notable Black people other than those who gained national fame were reared in the historic Deep Deuce milieu, some of which were mentioned in previous posts. A list of internet articles for your further study is at the end of this post.

According to this 2002 Journal Record article by Max Nichols,

Professor George O. Carney identified 48 jazz artists who were listed in major jazz publications in a 1994 edition of The Chronicles of Oklahoma.

* * *

The jazz giants who came out of Oklahoma remain largely ignored compared to the way we think about sports stars and other celebrities from Oklahoma. That’s probably because only The Black Dispatch wrote about them when they played in Deep Deuce places such as Slaughter’s Hall, Ruby’s Grill, the Aldridge Theater and the Ritz Ballroom. [Doug Dawgz Note: the Ritz Ballroom was not in Deep Deuce, it was at 15 ½ S. Walker.]Jimmy Rushing, for example, came out of Deep Deuce to become one of the most famous jazz stars of his time. He was known as Mr. Five by Five from 1935 to 1950, when he played in Count Basie’s band. Rushing, Abe Bolar, Walter Page, Don Byas and Lem Johnson played for the Blue Devils in Oklahoma City with Basie and helped Basie form his band in Kansas City. Eventually, nine Oklahomans played for Basie.

Carney listed 30 nationally recognized bands that included Oklahomans. Ten had three or more Oklahomans, including Basie, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Lucky Millinder, Woody Herman, Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, Cab Callaway, Hampton and Miles Davis.

Dr. Goins’ JazzImprov article says,

Charlie Christian is alive and kicking. His music still breathes down in the Deep Deuce – the legendary locale in the heart of downtown Oklahoma City, the place of discovery for the jazz guitarist who blazed a trail that stretched from the Southwest Territory all the way to East Coast of New York City. Jazz guitar players throughout the world are still reaping the benefits of the bop lines that he left us. Charlie accomplished a great deal in what is considered by most standards to be a minuscule amount of time – a mere four years, a blink of an eye. But you wouldn’t know that judging by the reaction when his name is mentioned on the streets of Oklahoma City.

It seems everybody knew Charlie Christian, or knew somebody who knew him. Among those who spent time on the Deep Deuce, Charlie’s legacy only grew, even if the reputation of Second Street died a slow and painful death over the years, until eventually it was all but gone and replaced by what is now known as ‘Bricktown.’ [Doug Dawgz Note: a forgivable error by an outsider.] This latest edition of the Deuce offers sleek condominiums and office space designed to bring young, affluent corporate movers to a town that – at least until maybe recently – hasn’t exactly earned the reputation as “the place to be” among American cities.

Meanwhile, Charlie’s name and legacy – along with world-renown novelist Ralph Ellison’s – remains synonymous with the incredible burst of traffic and energy that funneled through the city and supported the territory bands, and mothered what ultimately become known as “Kansas City Jazz.” Truth be told, many of those musicians who eventually established permanent residency in the old “Kaycee” originally earned their reputation on the Deuce, including Jay McShann, Count Basie, Lester Young, and Claude “Fiddler” Williams.

And, The Governor’s Gallery, Ron Tarver Exhibition gives this description:

Beneath the gleaming modern facades and upscale apartments along West 2nd Street, and the abandoned homes and weed infested lots to the east, lay the remnants of what was, in its heyday, one of the most successful African-American business districts in the country.

“The 2.” “The Deuce.” “Deep Deuce.” Akin to Harlem of the 1930’s – in spirit, if not in scope – Deep Deuce spawned such legendary figures as jazz guitarist Charlie Christian, “blues shouter” Jimmy Rushing, and internationally acclaimed writer, Ralph Ellison. Deep Deuce attracted African-American professionals of every stripe. Roscoe Dunjee, Dr. Frederick Douglas Moon, Mrs. Lucy Tucker, Dr. William Lewis Haywood, Mary and Sydney Lyons. These doctors, educators, entrepreneurs, and activists came together, creating a critical mass that transformed 2nd Street and the surrounding neighborhood into a thriving corridor of Oklahoma City.

The remainder of this post takes a look at some, but certainly not all, of the “Deep Deuce People” that the above introduction identifies.

ZELIA N. PAGE BREAUX. Is she a nationally known figure? No way … “mothers” and/or “mentors” don’t get national attention … even though she has received credit in such venues as The New York Times … but might she be considered to be the “mother”, at least the “mentor”, of several Deep Deuce persons who came to have that national status? YES, WAY! That being so, she will be the first person that I’ll identify here in some detail. A very nice image of the beautiful lady appears in William D. Welge’s Oklahoma City Rediscovered (Arcadia Publishing 2007), below.

As discussed in the previous Deep Deuce posts, she was a co-owner of the Aldridge Theater. But, more importantly, she appears by all of the accounts that I’ve read to have been of profound importance in shaping and motivating the young minds who learned from her at Douglass School, she being the director of music there as well as of all Black Oklahoma City schools in the “true” Deep Deuce era. Her pupils included Charlie Christian, Jimmy Rushing, and Ralph Waldo Ellison.

From the Oklahoma Women’s Network,

Oklahoma City native Zelia Breaux was director of music at Douglass High School in what is now Oklahoma City’s Bricktown area.

Breaux nurtured the talents of aspiring musicians including Charlie Christian (called “the world’s greatest jazz guitarist”) and blues vocalist Jimmy Rushing. She also instructed author Ralph Ellison (who attended Tuskegee Normal School and Industrial Institute on a music scholarship).

In addition to teaching music, she operated Ira Aldridge Theatre where many young musicians performed and taught singing at elementary schools.

Her father, Inman Page, along with classmate George Washington Milford, was the first black graduate of Brown University. He served as president of Langston University for 17 years and, late in life, was supervising principal of Oklahoma City’s separate school system for 12 years.

Zelia Breaux was inducted into the Oklahoma Women’s Hall of Fame in 1983 and was named one of Oklahoma’s “100 Notable Women of Style” by Oklahoma Today magazine.

From the fine article, Deep Second Still Lives In Dreams, in which the memories of the local Civil Rights leader Jimmy Stewart are stated, and in which he describes the 1924 Annual Downtown Boys Parade, the 1st such parade in which African-Americans had been allowed participation …

Stewart sits up a little in his seat now as he thinks back to the first Douglass students invited to march in the annual downtown Boys Day parade. Blacks had been banned from the parade before 1924. When the school superintendent decided to let Douglass students march, Breaux drilled her band, and the male teachers – some of them with ( military backgrounds) took the rest of the boys out on the football field every day and taught them to march with precision and decorum.

The parade began at Main and Broadway and traveled west, and Douglass was left to the end.

“Ralph [Ellison] was in the front, in the band. I wasn’t in the band, but I was marching with them, ” Stewart tells me. “And when we hit Main and Broadway, it was a show. People just looked out the windows, ‘Look at there at the Douglass High School,’ and the band was in step and the boys were marching like the military, whereas the Central High School boys were going along waving at people and just talking. It was a jolly thing to them, but our boys didn’t say a word. They marched just like soldiers.”

I ask[ed] Stewart how he felt, marching in that parade.

“Proud, proud,” he says.

* * *

“There were a lot of things to discourage one back then,” he says. “But there were also reasons to try to do things and we had blacks who wanted to do things. Mrs. Breaux was an inspiration to all of our young people to want to do something. “

I regret that I don’t have a physical picture of Ms. Breaux to give you, but, hopefully, a more important type of picture is derived from the remembrances of Mr. Stewart, above.

THE OKLAHOMA CITY BLUE DEVILS. The Blue Devils was/were Deep Deuce’s most widely known band. Beyond just talking about the Blue Devils, this section also serves as the introduction to some of the other individuals who will be more particularly described in this post by the time it is finished.

The Blue Devils at the Ritz Ballroom, 15 ½ S. Walker, 1931

Jerry Jazz Musician’s Kansas City page includes a cropped version of the above image and identifies the people, left to right: Hot Lips Page, trumpet; Leroy “Snake” White, trumpet; Walter Page, bass; James Simpson, trumpet; Druie Bess, trombone; A.G. Godley, drums; Reuben Lynch, banjo; Charlie Washington, piano; Rueben Roddy, tenor sax; Ernie Williams, director/vocals; Theodore Ross, first alto sax; Buster Smith, alto sax/clarinet, arranger.

The Blue Devils recorded and produced numerous outstanding artists, including Christian, Rushing, Walter Page, Oran “Hot Lips” Page, Lester Young, Buster Smith, Abe Bolar and Alvin Burroughs.

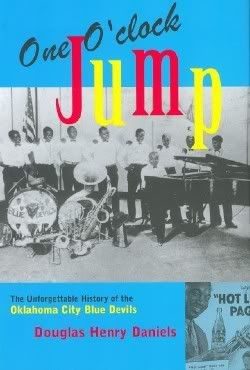

A book, One O’clock Jump: The Unforgettable History of the Oklahoma City Blue Devils by Douglas Henry Daniels (Beacon Press 2006) (click on the pic for a larger view), has been written about the band – see much more at this Amazon link, including this from the inside book cover jacket:

A book, One O’clock Jump: The Unforgettable History of the Oklahoma City Blue Devils by Douglas Henry Daniels (Beacon Press 2006) (click on the pic for a larger view), has been written about the band – see much more at this Amazon link, including this from the inside book cover jacket:

The legendary bandleader Count Basie once said of a Blue Devils performance, “It was the greatest thing I ever heard.” Now, in One O’Clock Jump, historian Douglas Henry Daniels tells the fascinating story of this incredible jazz band from Oklahoma City.

Though the Blue Devils survived in various forms from 1923 to 1933, their legacy has largely been overlooked. Individuals who played with the band – including writer Ralph Ellison (as a teenager), trumpeter Oran “Hot Lips” page, saxophonist Lester “Prez” Young, and bandleader Basie – went on to become celebrated artists of the twentieth century.

But, One O’Clock Jump is not just a history of the band – it presents a much larger view of Black history in Oklahoma, and, more particularly, in Oklahoma City. A significant amount of text is available at the above Amazon link from Chapter Two – Oklahoma City Pioneers. A very brief review of the book is presently at the KFOR-TV website. Additionally, a traveling photographic exhibit, Oklahoma: All That Southwest Jazz, sponsored by the Oklahoma Arts Council, is available to groups for a small fee through the Oklahoma Museums Association.

As noted above, though he was not an Oklahoman, the renowned Count Basie (1904 -1984) was active in and influenced by the Blue Devils. From a PBS biography,

Stranded in Kansas City in 1927 while accompanying a touring group, he remained there, playing in silent-film theaters. In July 1928, he joined Walter Page’s Blue Devils which, in addition to Page, included Jimmy Rushing; both later figured prominently in Basie’s own band. Basie left the Blue Devils early in 1929 to play with two lesser-known bands in the area. Later that year, he joined Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra, as did the other key members of the Blue Devils shortly after.

About the Blue Devils, Basie is quoted at Jerry Jazz Musician as saying,

“There was such a team spirit among those guys [The Blue Devils], and it came out in the music, and you were part of it. Everything about them really got to me, and as things worked out, hearing them that day was probably the most important turning point in my musical career so far as my notions about what kind of music I really wanted to try to play was concerned.”

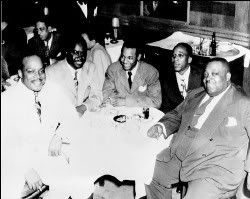

Even though this picture was probably taken in the late 1930s but certainly not later than 1942 (Charlie Christian died in 1942), I’m including it here because it shows Count Basie, Charlie Christian, and Jimmy Rushing: Left to right: Count Basie, Ernie Fields, Melvin Moore, Charlie Christian, and Jimmy Rushing. Click on the pic for a larger view.

Even though this picture was probably taken in the late 1930s but certainly not later than 1942 (Charlie Christian died in 1942), I’m including it here because it shows Count Basie, Charlie Christian, and Jimmy Rushing: Left to right: Count Basie, Ernie Fields, Melvin Moore, Charlie Christian, and Jimmy Rushing. Click on the pic for a larger view.

From The Count’s Account by Michael S. Harper, reviewing Good Morning Blues by Count Basie with Albert Murray:

Basie’s first band, formed in 1935-36, was made up of members of ”territory bands” in the Southwest, mainly Oklahoma. These musicians had come from strong, aggressive black communities – why else had these communities sprung up so far west? – and from good teachers, one of whom, Zelia Breaux, taught harmony and band at Frederick Douglass High School in Oklahoma City. She insisted that her students read music, played piano for the silent movies at the Aldridge Theater on ”Deep Second” Street and influenced the singer Jimmy Rushing and the guitarist Charlie Christian as well as Ralph Ellison, the novelist.

This was a time of traveling bands that played mainly in black communities. The musicians took care of one another on the circuit, which included Kansas City, Oklahoma City and other places in Oklahoma like Tulsa, Okmulgee, Boley and Muskogee. Those who formed the nucleus of the first Count Basie Band had paid their dues with the Blue Devils and later Benny Moten’s Band.

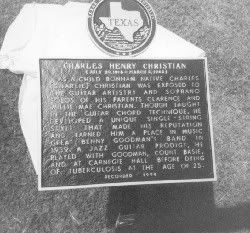

CHARLIE CHRISTIAN. Charlie Christian was the youngest of three boys of Clarence and Willa Mae Christian, his elder brothers being Edward and Clarence, Jr. After his 1916 birth in Bohnam, Texas, in 1918, after his father developed an unexplained illness that resulted in blindness, his family moved to Oklahoma City where his maternal grandmother already lived.

Charlie attended first grade at Douglass Elementary School in 1923, and he attended Douglas school until the seventh grade. There he met Mrs. Zelia N. Breaux who became involved in his musical life.

Before his father’s death, according to Charles Christian: Musician by Craig R. McKinney,

Charles’ musical career began when he was quite young; he too was involved in “busts.” His father had bought his two older sons musical instruments. Edward had a mandolin and Clarence, Jr. played the violin. To begin a series of “busts,” they would walk downtown; and after an OK from the establishment’s owner (usually these places were cafes and pool halls) they would play two or three pieces and pass a hat for tips. For the music people would maybe give a nickel, a dime, but a quarter was seldom seen. Edward didn’t care much for this practice because he felt it was ‘beneath his character’. It seemed to be too much like begging to him, but he continued to play. Most of the time they were in the downtown area, but sometimes on their way back home they would go through a white part of town. Here they would play music at homes. It was in this section of town they came to, because some people here had the little extra change for music. If the Christians knew someone liked music, they might approach their house, and quietly step up to the porch. Softly, they would begin to play their stringed instruments. People would come to the door; sometimes they might be given food, some gave a nickel or a dime, or perhaps a drink of whiskey. Although some wouldn’t give anything, they might compliment the family on their playing. And then, others wouldn’t. These were “busts.” This is what the Christians wanted to do. Clarence Christian Jr. recalls, “We weren’t all that great or nothing, but we had something to offer.” When Charles grew old enough to join in, he was just a board beater; but he “could dance real good.”

Charlie’s dad died in 1926 when Charlie was 10 years old, and elder brother Edward apparently assumed the role of “man in the house.” Craig R. McKinney describes an important night:

Not long after Charles became proficient on guitar (probably between 1929 and 1931) there was a jam session up at Honey’s. Honey’s was an after hours spot, run by Honey Murphy. It was an exciting place when the jamming started. When the jam sessions began “whole streets would just empty and go up to Honey’s.” Many bands came through town and when they came, they would jam at Honey’s. On this night Don Redman’s orchestra was there at Honey’s. The jam session included Edward Christian on piano and Ralph “Big Foot Chuck” Hamilton on guitar. Young Charles Christian walked in with his brother, Clarence. Charles was anxious to participate. Charles went up to the rest of the active musicians and pressed his brother, “Let me play one”.

And Edward’s reply was a classical, “Charles, don’t nobody want to hear them old blues.” Luckily Ralph Hamilton intervened on Charles’ behalf. He convinced Edward he should let his youngest brother at least have a chance. There is an explanation for Edward’s attitude. Edward didn’t know Charles had learned to play. Charles was asked by the group what he wanted to play. He chose a tune that most of the crowd knew and was popular with the people. He selected “Sweet Georgia Brown”. The choice was a surprise to Edward; but the band began to play with Edward setting the pace at piano. The song began with soloists each putting in their part. Then it was Charles’ turn.

“…so he licked his thumb, and gripped his pick the way he wanted it. And Chuck told him, ‘Come on, Charlie, you can do it. Charles set there, and they encored him back for sixteen choruses, and every one was different. And my oldest brother like to went through the ceiling. ‘Hey, hey man! This is my brother! This is my brother! Take another one, Charles. Take another one!’ You know he was going out, you know…”

His impromptu debut that evening was a surprise to many people. Charles’ sixteen choruses were single note solos and this was “way before he started playin’ professionally.” Charles’ brother, Edward, was very surprised, to say the least. Edward was unaware that Charles had been studying music and the guitar under Simpson and Hamilton. The simple reason for his ignorance was a difference that had come up between Simpson and himself. Both Edward and James Simpson were pursuing the same young lady. Because of this, very little was said between the two.

After this first number at Honey’s, everyone was quite excited and wanted to hear more of Charles on guitar. Charles was asked to choose another number. He politely and shrewdly explained he was not the leader of this session, he was just “sitting in” with the rest of the musicians. Actually Charles had only three songs he knew well, and wanted to play in front of others. He finally suggested they play “Tea for Two” and everyone agreed. Charles again electrified the awaiting crowd with his music. He exploded into his music, and the crowd reciprocated in appreciation.

After “Tea for Two” Charles thanked the rest of the guys for letting him play, telling them he felt better now. But everyone wanted to hear more. Charles was very aware he had only one more tune he felt secure playing with this group of musicians. The others begged him to play once more. He consented to one more number, and he chose “Rose Room”. The crowd was genuinely amazed by what it had heard that night, performed by a young, local musician. It was the talk of the neighborhood, and word spread fast. When Clarence and Charles arrived back home, their mother already ‘knew all about what had happened. And the effect of the incident on Charles’ eldest brother’s opinion of his baby brother’ talent was altered permanently.

And, the rest is history. Charlie Christian went on from there to become what some have called, “the world’s greatest jazz guitarist.” He auditioned with Benny Goodman in 1939 and was a member of Benny Goodman’s Sextet from that point forward until becoming ill in June 1941 and dying of tuberculosis on March 2, 1942, in New York City at the age of 25.

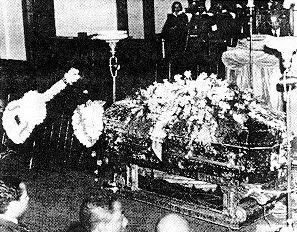

Click on pics below for larger view

Leaving Okc For Los Angeles … To Join Benny Goodman’s Sextet

Jammin’ at Ruby’s in 1940 … Funeral At Calvary Baptist Church in 1942

Charlie Christian had 3 funerals … NYC where he died, OKC where he was reared, and Bohnam, TX where he was born and buried

Charlie Christian has been inducted into the Big Band and Jazz Hall of Fame, the Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame, and lots of other stuff. The 1st Charlie Christian Oklahoma City Jazz Festival occurred at Stage Center in May 1985. From what I’ve been able to glean, Charlie Christian is perhaps the most beloved Deep Deucian, above all the rest … and the street on the east side of Bricktown Ballpark now bears his name.

JIMMY RUSHING. He wasn’t called “Mr. Five by Five” for nothing – a title he adopted and even composed a tune about himself by the same name – 5′ tall and 5′ wide, if you get the drift. The images below tell the tale …

According to Wikipedia,

[Rushing] was an American blues shouter from Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. He joined Walter Page’s Blue Devils in 1927, then joined Bennie Moten’s band in 1929. He stayed with the successor Count Basie band when Moten died in 1935. When the Basie band broke up in 1950 he briefly retired, then formed his own group.

Like the other “Famous Deep Deucians” who receive focus in this post, he, too, was influenced by Zelia Breaux, the mentor supreme of young Oklahoma City Black people in Deep Deuce’s prime era.

The “shouting” description flows from the fact that, early on, microphones weren’t always available and a vocalist’s “volume” needed to be strong to be heard above the instrumentalists if it would be heard at all. But, if one listens to tunes or snippets of tunes that are available on the internet, not much “shouting” is heard, only “smooth”. As was said in Key Magazine,

Novelist Ralph Ellison, who lived in the Deep Deuce during this same time period, recalled Jimmy Rushing’s voice “jetting like a blue flame in the dark… high and clear and poignantly lyrical… steel bright in its upper range and, at its best, silky smooth.”

A capsule version of Rushing’s history is contained in this link from Cascade Blues Association, in an article by Terry Currier, reprinted from the November 1999 issue of Blues Notes (and after discussing how he got to Los Angeles in the 1st place):

Jimmy was not happy with his life in L.A. and in 1926 he moved back to Oklahoma City to work in his father’s cafe. After a year and a half of working in the cafe, Jimmy went back to music. He joined up with Walter Page’s Blue Devils, in Little Rock, Arkansas. Jimmy knew Walter when they played together with Billy King. He played on Walter’s Vocalion records session in Kansas City in 1929.

The Kansas City visit opened the door to his musical future. He joined Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra and played all over the country. He also played on Bennie’s Victor recordings up through the middle 1930’s. In 1935, he joined up with Count Basie, one of the most popular musical acts in the country. Their relationship continued for the next 15 years. They played and recorded together and, in 1936, they recorded with Benny Goodman and Johnny Otis. Some of the best Basie material has Jimmy on it. His voice was the icing on a great cake. The Count Basie Orchestra appeared in a number of films including Crazy House, Take Me Back Baby, Air Mail Special and film shorts, Big Name Bands No. 1 and Choo Choo Swing. Jimmy was in all these, as well as the 1943 film Top Man. He also played at the famed “From Spirituals to Swing” concerts at Carnegie Hall in 1938.

Jimmy was a natural born entertainer. When he performed he was very animated and always had a smile on his face. Audiences loved him – both live and on the movie screen. Around 1950, Jimmy began to perform more on his own. In 1954, he and Count Basie appeared on the Tonight Show (Steve Allen was the host). His own recording output escalated, recording for Columbia, Okeh, King, Vanguard, and Jazztone during the 1950’s. He also worked with many other musicians, Including Buck Clayton, Frank Culley and Benny Goodman. In 1958, he and Benny Goodman performed together at the World’s Fair in Brussels and the Newport Jazz Festival.

During the 1960’s Jimmy was busier than ever. He performed all over the world with Dave Brubeck, Thelonious Monk, Eddie Condon, Harry James Orchestra, Joe Newman and off and on with Benny Goodman and Count Basie. Always a crowd pleaser, he was booked by most of the major Jazz festivals and venues. He appeared on several PBS-TV shows and also made an appearance on The Mike Douglas Show.

* * *

Jimmy is recognized as one of the finest singers of any style of music of this century. The British music magazine Melody Maker picked him “Best Male Singer” for 1957, 1958, 1959 and 1960 in their Critic’s Poll. The German magazine Jazz Podium named him “Best Male Jazz Vocalist.” He won Downbeat Magazine’s International Critic’s Poll as “Best Male Singer” in 1958, 1959, 1960 and 1072. They also picked his 1972 release “The You and Me That Used To Be” “Record of the Year”. The list goes on and on. He was simply amazing!

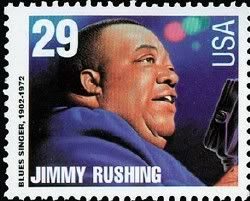

As far as I’ve found, Rushing alone (of the Deep Deucians) was deemed deserving of a US Stamp, this one in 1994.

As far as I’ve found, Rushing alone (of the Deep Deucians) was deemed deserving of a US Stamp, this one in 1994.

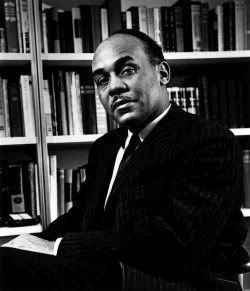

RALPH WALDO ELLISON. Ralph Waldo Ellison was born in Oklahoma City on March 1, 1913 or 1914 (sources vary) to Lewis Ellison and Ida Millsap Ellison.

Here, Ellison’s dad was a foreman on the crew that built the Colcord Building. The Medal of Freedom webpage says this about Ralph’s mother:

Ellison’s mother, Ida Millsap Ellison, who was known as “Brownie,” was a political activist who campaigned for the Socialist Party and against the segregationist policies of Oklahoma’s governor “Alfalfa Bill” Murray.

Who, in this time, wouldn’t? Governor Murray is a well documented racist through and through. It is to be recalled, by the way, that the Socialist Party was not such a taboo sort of thing during the early decades of the 20th century such as it is probably considered to be today.

After Ralph’s birth, he attended Douglass schools where he, too, fell under the umbrella of Zelia Breaux.

Although he does not appear to have returned to Oklahoma City very often, if at all, after leaving in 1933 to attend Tuskegee Institute, anecdotal information makes clear that his childhood roots and underpinnings, both good and bad, were here. In the very fine 1993 article, Deep Second Still Lives In Dreams, John Perry’s article included some telephone interview information with and about Ellison …

Ellison has returned to Oklahoma City just a handful of times in 55 years. But in Ellison’s dreams, he often wanders Second Street – not the burned-out disaster of urban renewal now soaking in the cold rain in front of Stewart and me, but the center of black commerce and culture of Ellison’s and Stewart’s childhoods, where black-owned stores and restaurants thrived, black lawyers and doctors worked, and nights throbbed with the music of Jimmy Rushing, Lester Young, and Charlie and Edward Christian.

“My early emotions found existence in Oklahoma City,” Ellison had told me by telephone from his eighth-floor Manhattan apartment that overlooks the Hudson River.

“In houses and in drugstores and barbershops and downtown, all of the scenes, the sights, the localities that are meaningful to me are in that city; my father’s buried there, and of course all the people who were heroes to me as a kid, my role models.”

* * *

[About Invisible Man]The rest of the country did notice Ellison’s novel about the journey of a nameless young black man from his southern home to college and then to Harlem as his illusions were shattered one after another.“Invisible Man” spent 13 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list — not quite two weeks for each of the seven years it took Ellison to write the book. It won the National Book Award in 1953, and a 1965 New York Herald Tribune poll of 200 authors, editors and, critics named “Invisible Man” the most distinguished American novel of the previous 20 years.

* * * “Invisible Man” has become a standard in college literature courses, and paperback sales remain brisk. In the Oklahoma City school district, students in high school advanced placement English courses now all read “Invisible Man.”

* * *

“Remember first and keep in mind that this is a book of fiction,” Ellison had told me, “and I was writing not about Oklahoma, but about the deep South where the old tensions were still very much present.”

* * *

Ellison has not returned to the city of his birth.“I hesitate to go back to Oklahoma City, especially now when I’m’ trying to finish a book,” Ellison said. “To go back and find that old East Second Street environment gone is traumatic, it’s sort of disturbing and I don’t want to lose the memories. I don’t want to lose my sense of how it was, because after all, that’s where I came from.”

The latter statement prompts mixed emotions in me – while it’s clear enough that he valued his upbringing in the Deep Deuce community, it’s also clear enough, and while his sentiments were understandable, that he had put Oklahoma City in a past-tense closed-door compartment which was wholly insulated from any present connection with his life as of 1993 in NYC. Except “in dreams”, it does not appear that Ralph Ellison considered himself to have any connection with Oklahoma City, but perhaps I am mistaken in reaching that conclusion. I’ve not walked in Ellison’s shoes and I’m certainly not saying, given his background, that were I in his shoes that I’d ever have come to become more temperate over time, or that I’d want to go back to the city of my roots, even if it was radically different … but, that said, I’d like to think that I would, and, in this, at least, I have some issues with Ralph Ellison.

But, back to the topic … Ralph Ellison and getting away from my opinions. Before he left Oklahoma City, he also took private lessons from Ludwig Hebestreit, the conductor of the Oklahoma City Orchestra, and, at 19 years of age in 1933, he took a state scholarship to attend Tuskegee Institute in Alabama to pursue the goal of becoming a composer or professional musician. Tuskegee, however, appears to have been a rather “conservative” social/political venue and, to boot, “jazz” was apparently not well thought of there. While still a student, he traveled to New York City in summer 1936 intending to return for his senior year, but he did not. Instead, he became acquainted with Alan Locke and Langston Hughes, “major literary figures of the Harlem Renaissance.” Emerson’s musical interests were jazz-oriented, and the social and political climate of Harlem and New York City probably suited him better. He met Richard Wright “who encouraged Ellison to write and published his first review in New Challenge, a journal that Wright edited.”

Literature became Ellison’s new path, and in 1952, after working on the project for seven years, his acclaimed novel, The Invisible Man, was published. The Medal of Freedom webpage describes the book:

Literature became Ellison’s new path, and in 1952, after working on the project for seven years, his acclaimed novel, The Invisible Man, was published. The Medal of Freedom webpage describes the book:

Invisible-Man was controversial, attacked by militants as reactionary and banned from schools because of its explicit descriptions of black life. Literary critics, however, generally agreed on the book’s significance. In 1965, a poll of literary critics named it the outstanding book written by an American in the previous twenty years, placing it ahead of works by Faulkner, Hemingway, and Bellow. Ellison received many awards for his work, including the National Book Award (1953), the Russwurm Award (1953), the Academy of Arts and Letters Fellowship to Rome (1955-1957), the Medal of Freedom (1969), and the Chevalier de l’Ordre des Artes et Lettres (1970).

A selection from the book’s Prologue reads,

“I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allen Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie extoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids — and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination — indeed, everything and anything except me.”

It is also clear that Ellison was “his own man.” This excellent PBS article by Anne Seidlitz says,

For Ellison, unlike the protest writers and later black separatists, America did offer a context for discovering authentic personal identity; it also created a space for African-Americans to invent their own culture. And in Ellison’s view, black and white culture were inextricably linked, with almost every facet of American life influenced and impacted by the African-American presence — including music, language, folk mythology, clothing styles and sports. Moreover, he felt that the task of the writer is to “tell us about the unity of American experience beyond all considerations of class, of race, of religion.” In this Ellison was ahead of his time and out of step with the literary and political climates of both black and white America; his views would not gain full currency until the 1980s.

Ellison did not only write about social issues, he also wrote about the great jazz musicians, including those mentioned above in this post. In Living with Music: Ralph Ellison’s Jazz Writings by Robert O’Meally:

While Ralph Ellison will forever be best remembered as author of the classic American novel of identity, Invisible Man, he also contributed significant essays on jazz that stand as compelling testaments to his era. His work included an homage to Duke Ellington, stinging critiques of Charlie Parker and Miles Davis, and recognition of the changing-of-the-guard taking place at Harlem’s Minton’s in the 1940’s. He wrote on musical topics from flamenco to Charlie Christian, and from Jimmy Rushing to Mahalia Jackson.

He was presented this nation’s Medal of Freedom award in 1969 by President Johnson. Ralph Ellison died in New York City of pancreatic cancer on April 16, 1994, and he was buried there. His adopted city has a monument near where he lived honoring his memory.

ARTICLES FOR MORE THAN YOU GET HERE. For those of you wanting more than what I’ve said or will say here, here’s a starter list of places to go.

- Books.

- Oklahoma City Music: Deep Deuce and Beyond by Anita G. Arnold (Arcadia Publishing 2010)

- One O’Clock Jump by Douglas Henry Daniels (Beacon Press 2006)

- Ralph Ellison: A Biography by Arnold Rampersad (Alfred A. Knopf 2007)

- Oklahoma City Internet Articles. Articles by Oklahoma Citians. Steve Lackmeyer and I have written the following:

- Deep Deuce History (Doug December 4, 2006)

- Famous Deep Deucians (Doug December 28-2006)

- History of Jim Crow in Oklahoma City (Doug May 1, 2009)

- Roscoe Dunjee: Fighter for Equality (Steve April 25, 2009)

- Ultimate Deep Deuce Collection (Doug April 20, 2009) — this reference includes an interactive Deep Deuce map and 34 mini-articles (some are less “mini” than others) on Deep Deuce history

- Additional Internet Resources. Additional resources having Deep Deuce relevance are:

- Excellent General Articles

- Deep Second Still Lives In Dreams The Oklahoman, John Perry, 1/8/1993

- The Count’s Account, by Michael S. Harper, reviewing Good Morning Blues by Count Basie with Albert Murray

- Key Magazine, 12/2005

- Zelia Breaux

- Charlie Christian

- Charlie Christian at NPR

- Charles Christian Biography by Wayne Goins

- Revisiting the Sound of Charlie Christian at NPR

- Jimmy Rushing

- Ralph Waldo Ellison

- Ralph Waldo Ellison (1913-1994)

- New York Times review of Ralph Ellison – Emergence of Genius by Lawrence Jackson

- New York City’s monument to Ellison showing “the invisible man”

- Living with Music: Ralph Ellison’s Jazz Writings by Robert O’Meally

- PBS’s American Masters Series: Ralph Ellison, An American Journey

- Wikipedia: Ralph Ellison

Navigate to …

Top of Article Deep Deuce People Background Zelia Breaux Oklahoma City Blue Devils Charlie Christian Jimmy Rushing Ralph Waldo Ellison