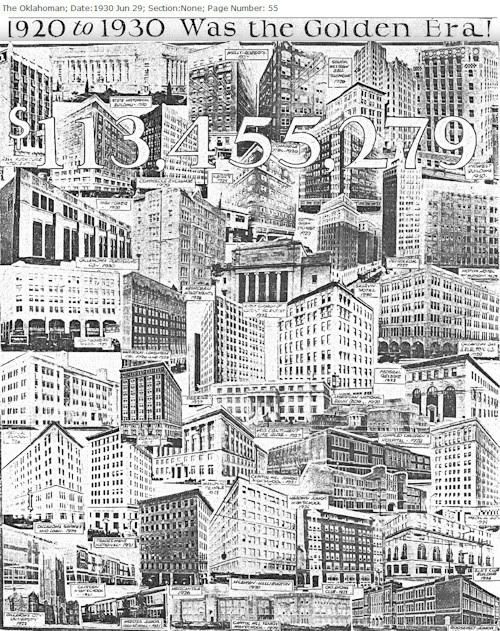

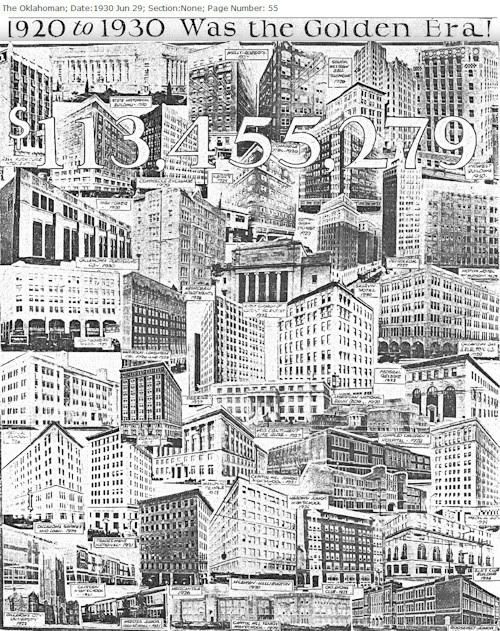

When researching What Became of the Downtown USO?, in the same Sunday Oklahoman issue which described the opening of the Bass Furniture & Carpet Building, June 29, 1930, I happened across the full page collage below, buried on page 14 of Section C.

I’ve now gone back to that Oklahoman issue and perused it more thoroughly — and as will be evident a lot of stuff was in that issue other than the announcement of the Bass Furniture Building which is 100 N. Main today. As well, I’ve looked past June 1930 to see what was proposed and what actually occurred through March 1932.

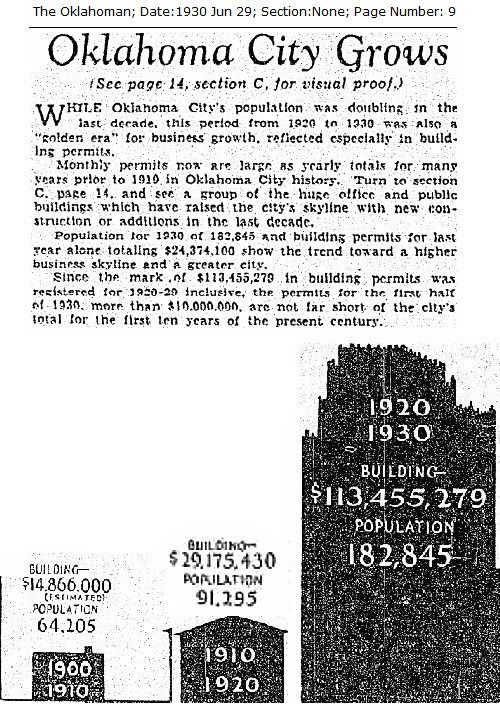

THE GOLDEN DECADE: 1920-1930. Page 1 of the June 29, 1930, issue contains the brief article below:

It said that the city’s population had doubled from 91,195 to 182,845, that building dollars had almost quadrupled from $29,175,430 to $113,455,279 and it said to go to page 14 in section C for visual proof — and that “proof” is the collage which started this particular article, and I’ll get back to that shortly.

So, you say that $113.45M over a 10-year period doesn’t sound like that much money? In today’s dollars, maybe not. But, in 1930, according to dollartimes.com’s on-line inflation calculator,

$113,455,279.00 in 1930 had about the same buying power as $1,386,726,936.29 in 2009. Annual inflation over this period was about 3.22%.

That’s 1 BILLION 386 MILLION (and change)! Now, I understand that what I’ve done is far from scientific since the $113.45M represents a dollar amount over a ten year period — but it does give a “feel,” at least.

JUNE 1930 TO MARCH 1932. Despite the October-November 1929 Wall Street Crash, at least through early 1931 Oklahoma City seemed relatively unaffected. Existing plans proceeded apace and new announcements were made.

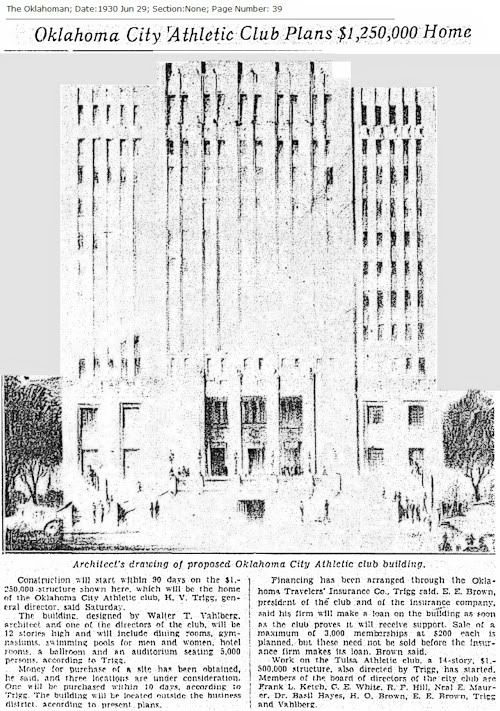

● Proposed Athletic Club. At page 39 of the June 29 issue was the announcement of a 12-story Oklahoma City Athletic Club, projected to commence within 90 days. One of the possible locations was downtown. However, the project never happened.

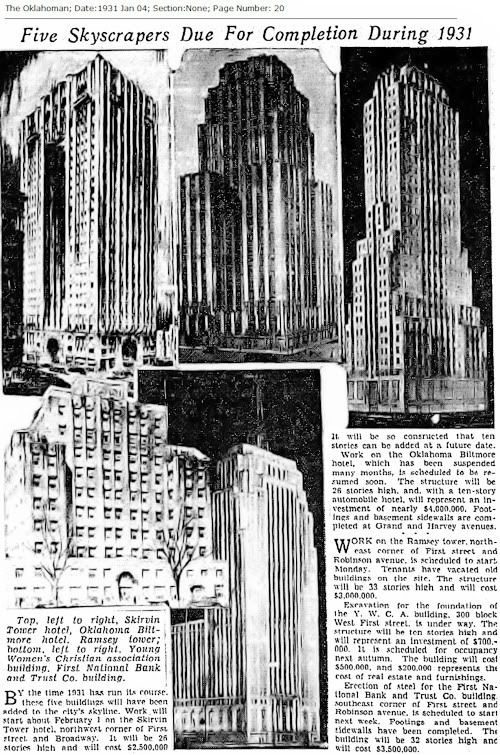

Optimism. By the June 29, 1930, newspaper article, announcements had already been made for the First National Center, the Biltmore Hotel and the YWCA, and on August 23, 1930, plans were announced for a 28-story Skirvin Tower, followed a week later by the August 31, 1930, announcement of the 33-story the Ramsey Tower.

As late as the January 4, 1931, Oklahoman article below, the article predicted that by the end of the year five new skyscrapers would be completed, First National, Ramsey Tower, Biltmore Hotel, Skirvin Tower, and YWCA. The article still describes the Skirvin Tower as being 26 stories in height.

See this article for more about the Great Race between 1st National & Ramsey Tower, both of which were completed in 1931. The new YWCA opened in September 1931. The prediction was a bold one, even if it was overly optimistic.

● First National & Ramsey Tower. This pair of projects did proceed rapidly. Walter Ramsey’s Ramsey Tower opened its doors on October 3, 1931. The First National Bank opened its doors to new customers on December 14,1931.

● Skirvin Tower. By this September 27, 1931, article, Skirvin Tower’s new height was said to be 16 stories (2 under and 14 above ground), yet the article optimistically said that when “finally completed,” the structure would contain 34 stories! Interesting it is that the height of the Skirvin Tower got both smaller and larger in the same article! The article predicted that the building would open in Spring 1932. As it developed, it opened in 1936.

● YWCA. The very large new YWCA did open on September 27, 1931.

● Biltmore Hotel. Following the January 11, 1929, Biltmore announcement, some preliminary construction began shortly thereafter. But, construction was not steady and sometimes stopped in its tracks for months at a time. The investors were determined, however, and, though not opening by the end of 1930 or even 1931, it did open on March 8, 1932. A May 3, 1931, article called it, “An Impressive Monument to Faith in Oklahoma City.”

SUMMARY OF THE GREAT ERA. Using but adding to the illustration in the June 29, 1930, Oklahoman, the following is a synopsis of Oklahoma City construction between 1920 and March 1932.

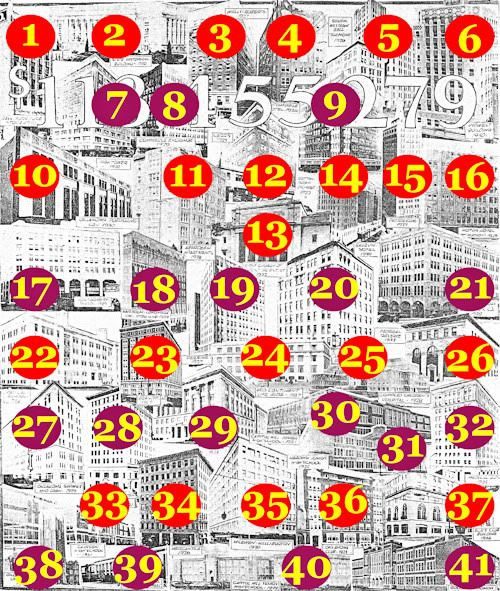

The Image With Building #s and Rows

- Row 1

- Bass Furniture (1930); today, 100 N. Walker

- State Historical Building (1930); on Lincoln Blvd. south of State Capitol, becoming home of Oklahoma Supreme Court

- Wells Roberts Hotel (1927); 15 N. Broadway; victim of Urban Renewal

- Automobile Hotel (on 1st Street) (1926); destroyed when 1st National Center expanded east to the Medical Arts (100 Park Avenue) Building

- Southwestern Bell Telephone (1928); NW 4th & Broadway

- Midwest Building (and Theater) (1930); 16 N. Harvey; victim of Urban Renewal

- Hightower (below Historical Building) (1929); 105 N. Hudson

- Commerce Exchange (1929); southeast corner of Grand & Robinson; victim of Urban Renewal

- Cotton Exchange and expansion (1924-1929); 228 R.S. Kerr

- OPUBCO expansion (1930); east of main OPUBCO building along NW 4th

- Aberdeen Apartments (1928); NW 15h & Robinson

- Kerrs Department Store (1925); 312 W. Main; victim of Urban Renewal

- 1st Church of Christ Scientist (1922); NW 11th & Robinson; vacant today

- Skirvin Hotel expansion (1930); Broadway at Park Avenue

- Petroleum Building (1927); 134 R.S. Kerr Avenue; now Dowell Building

- Motor Hotel (on Hudson) (1929); north of Black Hotel (One North Hudson today)

- Montgomery Wards (1929); southwest corner of Main & Walker

- Harbour-Longmire (1929); 420 W. Main (Main Place today)

- Perrine Building (1927); 119 N. Robinson (Robinson Renaissance today)

- American National Bank (1920); 140 W. Main; victim of Urban Renewal

- Oklahoma Gas & Electric (1928); 321 N. Harvey

- OU Medical School (1928); southeast corner of NE 13th & Phillips

- Braniff Building (1923); 324 N. Robinson; part of Sandridge Energy campus today

- Mid-Continent Life Insurance Building (1927); 1400 Classen Drive; Oklahoma Heritage Association today

- Crippled Childrens Hospital (1928); 900 NE 13th Stret

- Federal Reserve Branch (1923); southeast corner of NW 3rd (McGee) & Harvey

- Oklahoma Savings & Loan (1929); 306 N. Robinson; part of Sandridge Energy campus today

- Trademens National Bank (1921); 101 W. Main (City Center Building today)

- Masonic Temple (1923); 621 N. Robinson; Murrah National Museum today

- Capitol Hill Junior High (1921); 2717 S. Robinson, now Capitol Hill Elementary

- Harding Junior High (1925); 3333 N. Shartel

- Medical Arts Building (1925); 100 W. 1st, 100 Park Avenue Building today

- Classen High School (1921); NW 18th & Ellison; Classen Center for Advanced Studies today

- Mercantile Building expansion(1926); southeast corner of Main & Hudson; victim of Urban Renewal

- McEwen-Halliburton Department Store (1920); 327 W. Main; victim of Urban Renewal

- Oklahoma Club (1923); 202 W. Grand; became Tivoli Inn; victim of Urban Renewal

- Elks Club (1924); 401 N. Harvey; ONG today

- OCU (Administration Bldg.) (1922); on OCU campus along NW 23rd

- Webster Junior High (1929); 1100 N. Lindsay; became Moon Junior High; now used in Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

- Capitol Hill Senior High (1929); 500 SW 36th (Grand Blvd.);

- Roosevelt Junior High (1925); 912 N. Klein; today is OKC Schools administrative offices

- Sieber Hotel (1928)

- Hudson Hotel (1928-1930); NE corner of Grand & Hudson; victim of Urban Renewal

- Herriman Apartment Hotel – 5 story addition (1928); 923 N. Robinson

- Ramsey Tower (1931); northeast corner of Robinson & Park Avenue; City Place today

- First National Bank (1931), southeast corner of Robinson & Park Avenue

- YWCA (1931); 320 Park Avenue; victim of Urban Renewal

- Biltmore Hotel (1932); 200 W. Grand; victim of Urban Renewal

- Skirvin Tower (1936); sized back to 14 floors; now the 101 Park Avenue Building

Row 2

Row 3

Row 4

Row 5

Row 6

Row 7

Row 8

Others Not In the Collage Built By June 1930

Adding Those After June 1930

Of the 49 buildings listed above, twelve no longer exist with 10 being lost to Urban Renewal, as noted above. I didn’t list the Oklahoma City Athletic Club since it never got off the drawing board.

The Great Depression marked the end of the Golden Era. Downtown Oklahoma City would have to wait for many decades before the next such era might occur, if one ever does. The construction generated by Urban Renewal in the 1960s-1970s doesn’t begin to match the period, particularly if one subtracts the many buildings built during this period or earlier which were destroyed. Nor does the boom that we’ve been experiencing since MAPS I was passed match the downtown construction of the Golden Era. Perhaps, with the completion of the Devon Tower, another such downtown golden era may yet occur.