We’ve heard a good bit about the Oklahoman in recent months and years — most recently that its chief editor, Ed Kelley, is leaving (and by now that’s past tense) to become editor of the Washington Times (which item has been roundly discussed in this thread at OkcTalk.com). During the past two or so years, the Oklahoman has let go many of its employees due to economic reasons, but, more recently, scuttlebutt is that some Oklahoman employees are leaving by their own choice for reasons other than being let go by the paper. Like most locked secrets, the public will probably never know for sure what’s going on at the Oklahoman, or why — or, at least, it may take some time for that kind of thing to hash itself out.

| But there is a time in the past that such matters may not be quite as obscure — or, at least, some gleanings of the inner sanctum might be gleaned and evaluated.

In this regard, I’m pleased to present this guest article by Jim Kyle and also a brief interview at his home in Oklahoma City on June 15, 2011. Mr. Kyle was a reporter at the Oklahoma City Times and then the Daily Oklahoman from 1955-1959, and, if I get lucky, I’ll hopefully have another interview and another article (hence my optimistic title) before this is all done. Note: Jim has now done 3 articles. Click here for his second on prohibition repeal and click here for his third on the Korean War. |

Jim Kyle in 1957 Credit Cliff King, Photographer |

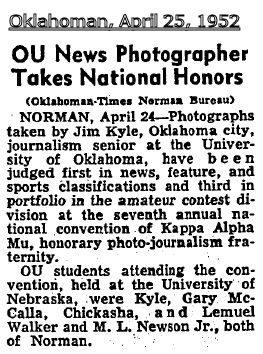

INTRODUCTION. Jim is a 1948 graduate of Classen High School and a 1952 graduate of the University of Oklahoma, School of Journalism. Before presenting Jim’s article, I’ll make a few comments of my own based on my review of the Oklahoman’s archives from 1950-1959. At the right is the first piece that I found, describing awards that Jim received at the annual convention of Kappa Alpha Mu, an honorary photo-journalism fraternity, during his senior year at the University of Oklahoma — doubtless a good way to start a career in journalism. However, as you will read below, there was a war on then, too, the Korean “Conflict,” as it was called, and that took his initial attention upon being graduated from O.U.

INTRODUCTION. Jim is a 1948 graduate of Classen High School and a 1952 graduate of the University of Oklahoma, School of Journalism. Before presenting Jim’s article, I’ll make a few comments of my own based on my review of the Oklahoman’s archives from 1950-1959. At the right is the first piece that I found, describing awards that Jim received at the annual convention of Kappa Alpha Mu, an honorary photo-journalism fraternity, during his senior year at the University of Oklahoma — doubtless a good way to start a career in journalism. However, as you will read below, there was a war on then, too, the Korean “Conflict,” as it was called, and that took his initial attention upon being graduated from O.U.

My review of the Oklahoman’s archives during his tenure with the Oklahoma City Times and then the Daily Oklahoman show a fairly wide diversity of subjects that Jim would be asked to cover. It appears that he was the principal reporter on seriously bad weather stories both locally and around the state — tornadoes, floods, severe winds, heat waves, and the like, but the stories I found most engaging were on other topics, and I’ve copied a few representative articles for your perusal — the Aurora Borealis/Northern Lights being visible in the city and state and its effects upon telecommunications; a pair of articles in December 1957 about how the Soviets use chess as a means of developing its scientific community (very important in the post-Sputnik technological push in this country) and another reporting on the U.S. State Department’s refusal to allow a Russian chess champion to participate at a tourney in Dallas, the entire city apparently being deemed off-limits to Russians; local high school rocket clubs in 1958; feature article on a local short wave radio fellow and his listening in round-the-world in the pre-internet era; a major piece on the 30th anniversary of Oklahoma City’s 1st humongous gusher; and, near the end of his tenure at the Oklahoman, a February 1959 piece about a local pastor’s criticism of proponents’ tactics concerning the repeal of Prohibition. Good reading, all.

I don’t know Jim well enough to hazard an educated guess, but my gut reaction from meeting with him and reading his piece below is that Jim Kyle, first and foremost, considers himself a journalist through and through and that his stint with newspapers during 1954-1959 evidences where where his heart really lies, life and economic choices notwithstanding. Actually, one might say that this article constitutes a piece of Jim’s re-entry into the journalism world, to the extent that can legitimately be said about publishing in a citizen blog. But, if I owned a newspaper, I’d surely want to include the fine article below.

JIM KYLE’S 1ST ARTICLE. Without further ado, below is the (first) guest article by Jim Kyle. I didn’t change a single word — no need existed since it was immaculately put together from start to finish. (I confess to having the need to look up the word, “miscreant” toward the end of the article — and of course its meaning was a perfect fit.)

June 19 edit: without withdrawing in any what I just said, on a closer read I did come across a few content errors and, upon asking Jim how he would like such things to be handled if at all, his suggestion was, “I learned more than 50 years ago that every writer needs a good editor in the shadows, to pick up such mistakes and fix them without changing the basic meaning or writing style. I use the ‘ed note’ often in the magazine, to add commentary and make corrections. I embed them in the story, but put them in parentheses and as separate paragraphs, all in italics, starting with ‘Ed. note:’ and ending with my initials, all to make it obvious that it’s not part of the original article. I think it adds a personal touch to the whole thing without impacting the integrity of the article itself.” This approach will, therefore, be followed below, and with no disrespect to the author intended.

OKLAHOMAN REPORTER — PART 1 By JIM KYLE Doug has asked me to help record some of the history of Oklahoma City’s newspapers, since I was a small part of that industry for a few years in the mid-50s. From 1955 to 1959, I was an employee of OPubCo; for the first year I was a copy editor “on the rim” at the Oklahoma City Times, which was the afternoon edition. At that point I moved to The Daily Oklahoman, first as their rewrite man but later became a general assignment reporter, and for the last year of that stay had the police beat. To misquote Charles Dickens, it was the best of times and the worst of times. To put it all in perspective I have to tell you a bit about myself. While in high school (Classen) I fell in love with photography, and set as my life goal becoming a magazine photographer. To this end I majored in journalism at OU, and while there served as the Oklahoman’s “campus correspondent” photographer. Upon graduation in 1952, I almost immediately went into the army as a second lieutenant of artillery, and thence to Korea. When I came home in 1954, I worked for a few months as a retail camera salesman and then got a call from The Daily Ardmoreite, Ardmore’s daily newspaper. They needed a reporter who could also handle a camera. I got the job. After a year, I returned to Oklahoma City. A reporter’s life on a small daily newspaper in the mid-50s was much like military service in Korea during the truce talks: days of boredom punctuated by moments of extreme excitement. While at Ardmore, I discovered my love of active reporting — and also learned the seamy inside aspect of the publishing business. First and foremost, it is a business, and the purpose isn’t to serve the public, but to make a profit for the owners. That often leads to compromise of one’s conscience. It’s not very much like the image presented by Perry White of The Daily Planet in the Superman strips. I learned early that my profession was not “saving the world” but instead “creating tomorrow’s garbage wrapper.” Some information that would have embarrassed “important people” never saw print; some arrests went unreported. Still, we loved what we did. Speaking of Perry, while at Ardmore I had a summer intern from OU follow me around for a couple of months. His name: Perry White. He later became editor of The Oklahoman, but only after I had been long gone from there, and sadly, he died just a few weeks short of his planned retirement date. Newspapering would do that to you. Once it got into your blood, there was a degree of joy mixed with stress that became habit forming. Not too many of us see long years of retirement. Notice that I used the past tense here. That joy seems to have disappeared in the past few years, and that’s partly why I’m writing this piece. Our city — nay, our world — needs to recapture it, or be much the worse for its loss. Enough philosophy for now. Let’s look at the history of newspapering in OKC, with special emphasis on OPubCo as I saw it both from the inside and from the outside today. My knowledge of it starts in 1903, when the gold rush at Cripple Creek, CO, began to play out and a young promoter named Edward King Gaylord moved from there to Oklahoma City. Like many other civic minded folk in many other pioneer towns, he established a newspaper to express his views. (Ed. note: EKG did not establish the newspaper. Instead, he purchased a minority interest from the then owner, Roy E. Stafford, the Daily Oklahoman itself having been established by Rev. Sam W. Small in 1894. Note, too, that the “Oklahoma City Times” Jim references in the next paragraph is not the paper by the same name which was initially published in Wichita before the April 22, 1889, Land Run. Instead, the paper he is referencing is the paper initially named “Oklahoma Times” owned by Angelo C. Scott and his brother W.W. Scott, it being first published on May 9, 1889, but which paper was soon renamed to be the “Times-Journal” and, some years later, the “Oklahoma City Times.” See Angelo C. Scott’s “The Story of Oklahoma City” for more. DL) There was already a thriving newspaper here, though. The Oklahoma City Times had been serving the area since the Run of 1889. First published from Wichita (as I recall from my long ago history lessons) it had moved to OKC soon after the first permanent buildings were erected, and was well established. Its publisher and Gaylord battled for survival for several years. Eventually, Gaylord won, purchased the Times, and made it the afternoon edition of the Oklahoman. This allowed him to claim that his company had served OKC since 1889 — a boast appearing on the front page of every issue of both papers so long as the Times existed (it ceased publication several decades ago), although I’ve not seen it lately. As OKC grew with the oil boom of the 20s, so did OPubCo. The Daily Oklahoman became recognized as the almost official newspaper of the state (although Tulsa’s two papers hotly contested the claim) and its circulation reached out into adjoining states. This growth did not escape the notice of the major national newspaper chains, and in the early 30s the Scripps-Howard organization created The Oklahoma News, attempting to take over at least a part of OPubCo’s power. (Ed. note: Edward Willis Scripps founded the “Oklahoma News” in 1906. The publication group was renamed as Scripps Howard in 1922. See Scripps Group Chronology. The “Oklahoma News” ceased publication in 1939. DL) As had happened with the Times so long before, the two organizations battled fiercely for a time. OPubCo finally forced the News to close its doors, by the simple process of refusing to accept advertising from any merchant who dared advertise in the competing publication. While Scripps-Howard took the matter to court, and won a permanent injunction against such a practice, the damage had already been done and the News failed in the mid-30s. As the OPubCo empire grew, with establishment of one of the first commercial radio stations west of the Mississippi (WKY) and a delivery service (Mistletoe Express) that covered the state, the company remained a private corporation. Originally most of the stock was retained by the Gaylord family, but some was made available to senior employees. One of those was the Oklahoman’s managing editor, Walter Harrison, known to one and all as “The Skipper.” When Pearl Harbor catapulted the nation into World War II, The Skipper was one of many men who left civilian life behind and joined the military. Opinions vary as to what happened to him during his military service. It’s indisputable, however, that upon his return to civilian life, he and Mr. G (as Gaylord was known to all his employees) parted company rather acrimoniously. OPubCo is said to have attempted to reclaim his shares, but he succeeded in retaining ownership of them and for the rest of his life, published detailed accounts of every OPubCo stockholder meeting in the small Nichols Hills weekly he created. I’ve been told by a former employee of The Skipper that he also kept a dossier on every editorial employee of OPubCo (including me), and a set of files that would “blow this city wide open” if ever made public. He used the threat of such publication, I was told, to keep the power at least partially leashed. The Skipper died while on a business trip in the early 60s. His secret files, if they existed, never saw the light of day. So what was it like on the rim of the Times in 1955-56? The “rim” refers to the large horseshoe-shaped desk that was a fixture in every newspaper city room in those years. The news editor sat in the center and copyreaders sat around the rim. As I recall there were four of us. The assistant city editor also had a spot on the rim, as did the makeup editor. It was the nerve center of the publication. Copy boys would bring print from the teletype machines to the news editor, who would select which items he wanted to include, and assign headline sizes to each. He would then toss them to whichever copyreader had nothing to do at the moment; we were encouraged to work crossword puzzles when not actually working, so that the news editor could see who was available for the next article. The headline sizes were coded by number. Over the years I’ve forgotten most of the codes, but one sticks in my mind: the 11 head. An 11 head meant three lines of type, one column wide, with each line sized to come within one or at most two characters of the right side of the column. These size requirements made headline writing a fine art; we had to show the meaning of the article and still fit it perfectly. Sometimes, we goofed. I still remember an 11 head that I put on an article for the market page, about a sudden rise in the price of soybean futures as traders scurried to cover short sales: “Beans Spurt/As Traders/Cover Shorts” were the three lines. Not until city editor Ralph Sewell posted it on the bulletin board the next day did I realize all the multiple entendre in those three lines of black type — but I wondered why somebody had changed it for the second edition! Writing headlines was only a minor part of the copyreader’s duties. We checked the spelling of every word, made sure that capitalization followed the rules set forth in our style book, and on occasion trimmed articles to make them fit into their allotted space. All articles were written with the most important content at the front, and importance diminishing with length, so that they could be trimmed to fit without requiring rewrite. Such attention to detail is one of the things that seem now to be missing! Since the Times was an afternoon paper, my working hours were 6 a.m. until 2 p.m. Monday through Friday. It didn’t publish on Sunday, and I had one other day off during the week. As I recall, it was Tuesday. Our first edition of the day would come off the presses about 10:30; it was the one shipped to outlying areas and made available for street sale, but had very little local content. Most of it was feature material — we called it boilerplate — meant simply to occupy the space between the ads. The Home edition came out around noon, allowing time for distribution to all the carrier stations. It contained real news. The final edition of the day was the Blue Streak, intended primarily for street sales, and its stories tended to be more sensationalized than those in the Home edition. As each edition came off the presses, we on the rim got some of the first copies and we immediately went through them looking for errors so that they could be corrected before the bulk of the press run was done. After about a year on the Times, I was told to move over to the Oklahoman. That was the position I had yearned for since leaving Ardmore, so I had no hesitation at all about accepting the transfer. My initial assignment was as the rewrite man. The hours were 4 p.m. to 1 a.m. I had a desk immediately behind city editor Chan Guffey’s spot at one end of the rim (the fourth floor of the old OPubCo building held both papers in the same huge room, and each paper had its own copy desk). My job was to handle any assignment Chan gave me, but primarily to take incoming phone calls from the field reporters, and type their stories. To take dictation by phone, I had one of the two electric typewriters in the room, and it became a sort of game for us to see how fast I could do it without asking the other fellow to pause while I caught up. Eventually this got me up to around 120 WPM typing speed — but that speed is gone forever. I also had to write the obituaries every evening. In those days, the Oklahoman and the Times both published obits without charge to the families. About 4:30 every afternoon, I would call all the local funeral homes and get the names and phone numbers of the families for that day’s deaths. I hated to invade their privacy, but soon learned that in most cases the families really wanted to talk to me, and that made the job easier. I did, however, have to beg off on two obits during my time at that task. One was of a young co-worker with whom I had shared a 10-day Air Force junket to Europe while I was at Ardmore. The other was the baby son of close friend and fellow staffer John Gumm (John himself died in a house fire less than a year ago). In addition to doing the obits, I also got the job of writing the daily weather story. This, in turn, led to some of my first outside assignments, when severe weather hit early enough in the evening to give us a chance to cover it. I recall one night doing a wild drive from OKC to Ada to cover such a storm; it didn’t hit until after 6 p.m. and I had a 10 p.m. deadline. By all rights I should have wound up in a tangled mass of wreckage somewhere along the way, but I made it and got the story called in on time. Chan had one policy that I loved: one of the first things he told me when I started working for him was to bring a book with me every day, and to read it when I had nothing else to do. Under no circumstances was I to look busy when I wasn’t. His reasoning was that he wanted to be able to tell instantly if I were ready for an assignment, at any time during the evening. I did a lot of reading during the years I was on the rewrite desk! After a couple of years on rewrite, Chan began giving me outside assignments from time to time. Most were feature stories, such as interviews with Jimmy Stewart, Jock Mahoney, and Lucille Ball. Then police reporter Jack Jones decided to get out of the business, and I was tagged to become his replacement. I rode with Jack on the beat for a couple of weeks before taking it over in full, and learned more about the underside of Oklahoma City at the time than I really wanted to know. However it was exactly the kind of reporting I had learned to love at Ardmore. My daily routine was to go to the police station, check the blotter, write up a dozen or so one-paragraph items about arrests and minor things, and then stay alert for anything that might happen. As police reporter, I had a special auto in the OPubCo fleet. It was a Ford Interceptor (the police model) equipped with two-way radio to the city desk and a monitor for the police band. I would check out the car from the garage first thing, go to the “cop shop” next and then to the sheriff’s office in the courthouse, and from there things would vary depending on the activity each day. I often stopped for supper at Priddy’s Diner; any time I left the car, I would radio Chan and tell him where I was so that he could get in touch with me. One evening I was at Priddy’s and about to carve into my cheese steak when the phone rang and Mr. Priddy handed it to me. There had been a murder-suicide in Stockyard City. I left the steak on the counter and took off. The story turned out to be trivial from a news point of view: a domestic dispute gone violent, and the man killed his wife and then himself. I got the facts, drove back to Priddy’s, finished my steak, then went to the office and typed the story up. During my time as police reporter, a close friend introduced me to his fiancé, asking me for my opinion of her. I liked her from the start. The friend, on his way to becoming a full-fledged alcoholic, would disappear from sight for a couple of days at a time. His fiancé, worried, would enlist my aid to search for him. She and I became close friends, and then more. In February of 1958 we were married. It was years before the ex-friend and I spoke again. Chan gave me an extra day off for my wedding, but I then had to go back to work. I put my new bride in the car alongside me, and almost immediately after the initial routine the police dispatcher issued a “man with a gun” alert for an address on the southeast side of town. Naturally, I took off for it. When I got there, I parked about a block away, handed the radio mike to my bride, and told her to contact the office if she heard any shots fired. Then I headed for the action. Fortunately, there was none. It had been a false alarm. However she had gotten a great initiation into the life she had chosen to spend with me! It wasn’t the only time we went into potential danger together. She rode with me often, until becoming pregnant. Even then, she was with me the night I got an “officer needs help” report while at the sheriff’s office in downtown OKC. I took off following a deputy, riding on his red lights and siren. We were doing a little over 90 MPH up Walker at 9 p.m., and the speedometer was pegged at 120 when I crossed Eastern on NE 23, blasting through a red light as I did so. When the deputy pulled out to pass a long line of traffic, on an uphill stretch of the two-lane highway, I dropped back. At Ardmore, I had covered the three-fatality result of such a head-on crash and had no interest in becoming part of another one. When I finally reached the scene of the action, near Spencer, it turned out that a miscreant had bitten the officer who “needed help.” No story at all. After that, my wife didn’t ride with me much. It was a difficult pregnancy, too, and she spent much of the last couple of months lying on the couch. Finally about midnight one night in early April 1959 she told me “It’s time” and we set out for the hospital. I called the police dispatcher (by that time we all knew each other; I even had the call number “Unit 231”) and told him I was leaving and had no plans to stop for any traffic lights. On the way I drove sensibly, for a change, and we hit all the lights on green. There were no problems, and her labor was blessedly short. With a new family, I found the pay of a reporter, even one near the top of the scale, woefully inadequate. I had been moonlighting for a year or so, writing articles for ham radio magazines, but that income was too irregular to depend upon. When a recruiter from RCA Service Company came to town looking for potential electronics technical writers, I went to see him, showed him my qualifications, and took his exam. A few days later I got a call inviting me to Los Angeles for an interview. I went, got an offer, and that was the end of my career at OPubCo. I should say a little about the physical plant during those years. In addition to the main building that still stands at NW 4 and Broadway, there was a second larger building to the east, adjacent to the railroad tracks, that housed the presses. Those presses were huge machines that used cast rotary images of the pages to put the ink on the paper, and giant rolls of newsprint to feed them. That’s why the building was next to the tracks; paper arrived by the carload! The type for each story was cast into lead by Linotype machines; the headlines were similarly cast by devices called Ludlows. (While I call the metal ”lead” it was actually an alloy of tin, lead, and antimony, designed to maintain crisp edges when cast into molds. Once it had served its immediate purpose, it went back into the vats to melt down and be used again.) Printers arranged the lead into page forms called chases, under direction of the makeup editor. Strict union rules forbade editorial employees from even touching the type itself; to identify a problem area to a printer, the editor had to point to it with a pencil. Not long before I went to work there, the company had a run-in with the pressmen’s union that caused a walkout by all union members; however when the picket lines vanished the printers returned to work. When all the articles and ads for a page had filled a chase, the printer pulled a full-page proof from it and sent it to the proofreaders for a final check. Once the proof had been okayed, he placed a paper-mache sheet called a “mat” (for matrix) on it and put the sandwich into a steam press to transfer everything to the mat and form a mold. The mat then went into another machine (the name of which I’ve forgotten, if I ever knew it) that wrapped it into a half-cylindrical shape and made a lead casting of the whole thing. That casting is what went onto the press to do the actual printing. The process for each page took several minutes, and we usually had from 32 to 64 pages in each edition of each paper. Attaching the plates to the presses was a slow job, as well, so the press room was always a beehive of activity to meet all the deadlines. An elevated and enclosed catwalk or skyway that we called “the tunnel” connected the two buildings, running from the third floor of the main building to the second floor of the pressrooms. The ground beneath the tunnel formed an employee parking lot for those of us on the night side; executive vehicles occupied it during the day. Copy went from the city room to the press area through pneumatic tubes, the same sort now found at bank drive-thru areas but in those days only used by newspapers and some retail outlets such as the downtown J. C. Penney store. The night that Sputnik appeared in the sky, in November of 1957, the front page was replated more than a dozen times during the run of the final home edition between midnight and 4 a.m. Each time a new dispatch came in on the AP wire, we would stuff it into a carrier and put it into the tube. The editors were in the press room directing changes to the chase for the front page. As each new batch of material arrived, a new mat was created, the presses stopped just long enough to change the plates, and then they rolled again. Only a few homes got the final version, but we all considered the effort as nothing more than what the job required for a fast-breaking story of such significance. When I went to RCAS, my starting salary was $125/week plus overtime. That was more than Chan was getting as city editor, and $30/week more than my pay as police reporter. It turned out that the overtime involved minimum 100-hour weeks, so the dollars were great — but so was the cost of living on the west coast. That, plus homesickness, brought us back to OKC in 1962 and we’ve been here ever since. After a year as editor of three trade journals, a stint with University Loudspeakers, and two years of free-lance writing, I went to work at the then-new G-E plant and spent the next 24-plus years there (through three successive owners). Then came two years at Norick Software (one of Ron’s lesser-known projects) before I finally retired. So what has caused the obvious decline in stature of print journalism in Oklahoma City over the past fifty-plus years? The low pay, traditional in the newspaper business for as long as I’ve known anything about it, is probably one of the reasons for the decline. The absolute need to cut costs to a minimum is undoubtedly a more major reason, though. The use of proofreaders seems to have become outmoded, so spelling and grammar errors abound — things that people like Ralph Sewell, Dave Funderburk, Chan Guffey, and even Mr. G himself (who was still running things during my years there; he died at the age of 103 leaving the business to his son Edward) would never have tolerated. A decline in advertising revenue is also an important part of the picture, together with a general drop-off in literacy of the younger generations — not that they’re unable to read or write, but that they don’t particularly want to. So there’s my contribution to the history of Oklahoma City’s newspapers. Definitely incomplete, but at least it’s a start… |

I was especially pleased to read that last part … “it’s a start.” Here’s hoping that Mr. Kyle will have much more to say on the city’s journalism or other history and thoughts about the same in the very near future!

| JIM KYLE VIDEO INTERVIEW #1 — June 15, 2011. Again, I’m being optimistic that there will be at least one additional video interview. I did this first one at Jim’s home in northwest Oklahoma City with my cell phone so that accounts for the poor video quality. I’ll see if I can find better equipment for the next. Although the video quality leaves much to be desired, the audio should come through just fine. |

I call your attention to Jim’s comments beginning around 2:32 about the “seamy side” of the newspaper business.

But, I also learned the seamy side of the newspaper business … found out how often we had to compromise with our consciences things that might embarrass an advertiser frequently didn’t get reported and if “important people” would be offended, again, the story would not see the light of day.

***

I’d been there [in Ardmore at the Ardmoreite] about a year when there was a showdown between my managing editor who I considered to be my boss and for that matter my mentor at that time, and the owner of the paper, and it ended up with the editor getting fired. Our city editor was promoted to the managing editor’s spot. They offered me the city editor’s spot, but being young and idealistic I decided I didn’t really want to have any more to do with them. So I hightailed it up to Oklahoma City and visited the Oklahoman.

Interesting recollections they are that you have about the dark side, young Skywalker.