Latest revision on 8/30/07 to ad several images and make corrections.

Go To Trains 3 Go To Trains 3A Go To Trolleys 1

From the early Oklahoma City train days, trains, both freight and passenger, continued to flourish in Oklahoma and in Oklahoma City. Oklahoman articles, noted below, say that during the year 1917 there were as many as 10 Santa Fe railroad passenger trains through Oklahoma City daily, 16 Frisco, 10 Rock Island, eight Katy and four Fort Smith & Western,” and another article said that Oklahoma City had as many as 50 passenger trains a day during the period during and just after World War II. By April 1972, only a few Santa Fe passenger operations remained, and, by October 1979, the number of passenger trains in the entire state was down to zero, nada. After a 20 year hiatus, a limited Amtrak presence returned to Oklahoma City in 1999. Okc Trains Part 2 tells a bit of the story and gives some links elsewhere for more.

In this post, unless otherwise stated, click an image for a larger view.

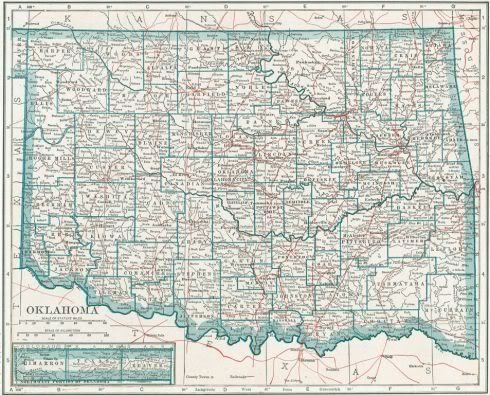

FIRST … A FEW MAPS. You already know how much Doug Dawg loves his maps! Here are a couple of railroad maps that you might enjoy (some others are in Okc Trains Part 1).

Click the map for a larger image

For a high resolution version, click here

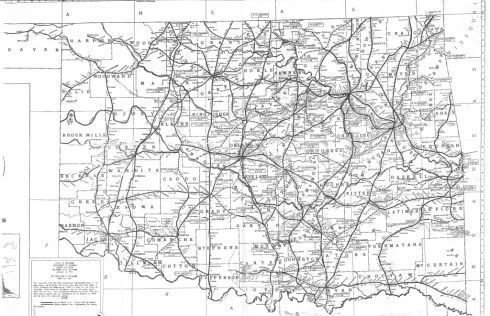

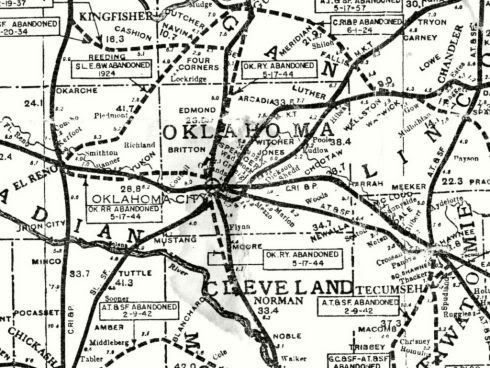

Above But Cropped to Oklahoma County

Larger Image Not Available

Oklahoma Department of Transportation, 1925-1970

Click the map for a larger image

For a high resolution version, click here

From My Oklahoma Map Collection (dashed lines are discontinued railroads)

The text in the lower left corner of this map reads: “The film for this map was reproduced photographically at the same scale as original official paper map obtained from the State Corporation Commission, 1925 Edition, by the State of Oklahoma, Department of Highways, Survey Division, where both are on file. All railroads constructed after 1925 have been added hereon and all abandoned up to January 1, 1970 are so depicted, both by legend.”

TROUBLES IN THE 20s. Probably, there were others, but this section focuses on only 2: The Great 1923 Flood, and the Clearing of Downtown.

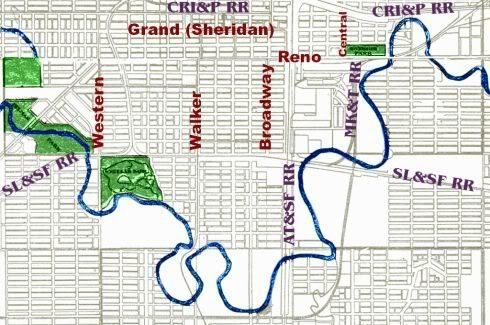

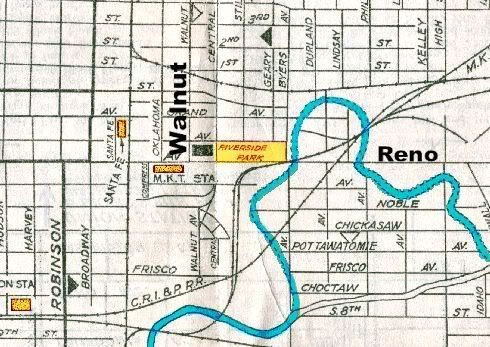

Trouble In River City. I’ve seen pictures before, as you probably have, of “The Great Flood” which hit Oklahoma City hard in 1923. The North Canadian meandered wildly just south of downtown and, in fact, above Reno just east of the Santa Fe tracks (that’s why older maps show a “Riverside Park” on the north side of Reno as shown in the cropped and colorized 1911 Planning map and Manley 1940s map below). “Walnut” (“Mickey Mantle” in that area today) is on the west side of Bricktown Ballpark, to give you a better idea of what you’re looking at below.

1911 Planning Map (Click map for alarger image)

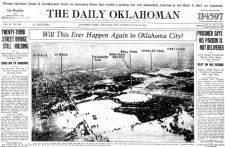

So, when researching the Oklahoman’s archives for this article, when I ran across a page 1 story called, “Worst Flood Since 1904…,” and others in the same vein and time sequence, I thought I’d found what I was looking for. The headlines speak for themselves – click on an image for a larger view.

May 27, 1923 |

May 29, 1923 |

June 10, 1923 |

June 11, 1923 |

June 12, 1923 |

June 14, 1923 |

June 16, 1923 |

|

I thought that I was done! But … NO! Some things just didn’t match up, such as the National Weather Service listing the North Canadian flood of October 13-16, 1923 (and not May and June, 1923), as being among the state’s top weather events of the 20th century … not in the top 16 but in the “others” category.

I searched further in the Oklahoman’s archives and found that, in fact, the question posed in the June 14, 1923, headline, above (Will This Ever Happen Again To Oklahoma City?), was answered YES! in October of the same year. Here are a couple of headlines from the Oklahoman:

October 17, 1923

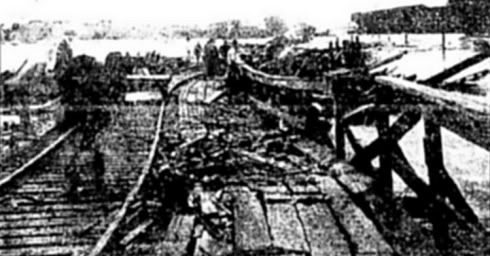

The above article calls this the “East Frisco Bridge”

Larger image not available

Then, looking more closely in a couple of my books, it appeared that text and images in the venerable Vanished Spendor II and Griffith’s Oklahoma City: Statehood To 1930 were being mixed and matched inaccurately with the respective 1923 floods – that is, unless each reference was referring to both 1923 floods in a collective way. For example, Griffith’s Chapter 8, “The Great Flood,” includes images from both the May-June and October floods in the same chapter and context. Vanished Splendor II does the same in it’s Images 312-315 – the picture of Overholser Dam overflowing, below, has hard-to-read but nonetheless legible handwritten text written on the image, “June 1923” (observable in the same pic at Griffith, page 110 – it’s the same pic as 313 in Vanished Splendor II although the handwritten text at the very bottom showing a date does not appear in #313 as it does in Griffith’s book.

So, who has got it right? The writer of “handwritten text” on images, Griffith and/or Vanished Splendor II, the National Weather Service, who? I’ll go with the National Weather Service, just as a guess, establishing October 1923 as the holder of “The Great Flood” title.

As an aside, Edwards and Ottaway say, in Vanished Splendor II (#s 313-315), that,

Later that same morning Mayor O.A. Cargill issued a special proclamation to the Citizens of Oklahoma City stating that “for the protection of property within the flood district, police and soldiers on duty have been ordered to shoot to kill any person found looting and breaking into any abandoned house or store building.”

That’s a dandy quote but I was not able to locate it in searching the Oklahoman’s archives as to either of the 1923 floods.

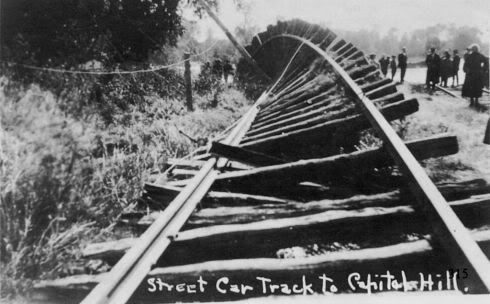

The points are (1) it’s really hard to know whether “The Great Flood” was in May-June or October 1923, and (2) unless handwriting is on an image or some other verifiable source gives a date, the images which follow are from either one flood or the other, and I’m not always sure which to match with which. Either way, though, damage to both local and interstate rail was serious, just as was true for the whole region in the North Canadian flood plane below Overholser Dam. With those qualifications, here are some pics. The 1st pic is from Griffith’s book since it shows a part of the handwritten date.

Santa Fe From My Postcard Collection, I’m guessing May-June, 1923

Trolley Tracks in Capitol Hill, I’m guessing May-June 1923

Credit Vanished Splendor II by Edwards & Ottaway (Abalache Book Shop Pub. Co. 1982)

Howard Johnson, Associate State Climatologist for Service (Retired), wrote this about the October 2003 flood (click here to open his article):

A more famous October flood, and surely one that had an enormous social impact, was the October 13-16, 1923 North Canadian River flood that caused great devastation in Oklahoma City. The floodwaters, produced by copious rains in the river’s northwestern Oklahoma watershed, breached the earthen embankments of the Lake Overholser Dam and caused $15 million (1923 prices) worth of damage in the capitol city.

An October 17, 1923, article in the Washington Post begins:

Virtually isolated by the greatest flood in its history, Oklahoma City tonight sheltered its little army of refugees and waited for the muddy, turbulent expanse of the North Canadian river to recede and reveal the damage it has wrought.

Many more photographic images of one or the other “Great Floods” will be in the Okc Trolleys post, to be written after this one is done since that’s what I have the most pictures of.

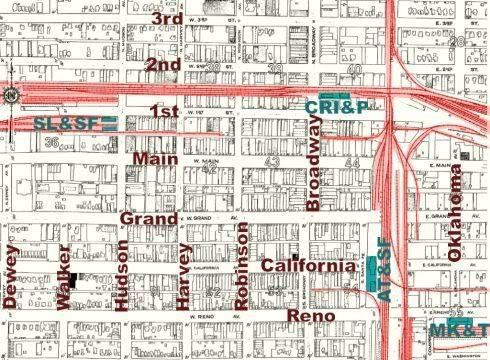

A Downtown Divided. While attraction of major rail carriers was a goal pursued hotly by early day Oklahoma City pioneers like C.G. Jones and Henry Overholser, and while success in that regard was attained by persuading the Frisco and Rock Island lines to become focused upon Oklahoma City, it was not without the practical cost of making pedestrian and vehicular traffic most difficult and, given the volume of rail traffic in the early years, impossible at times. All downtown intersections of street and rail crossings were “grade crossings” and, of course, trains had the right of way. To move east and west to/from “downtown” and what is now “Bricktown,” crossing the Santa Fe tracks was required. To move north and south in downtown between 1st Street (Park Avenue) and 2nd Street (Robert S. Kerr), crossing the Frisco and Rock Island tracks had to happen.

This all comes home visually by looking at another map, this one being a cropped and colorized look at a 1922 Sanborn Map. Co. image of a slice of the central business district, below. I’ve highlighted downtown rail – notice that very often it wasn’t just crossing “a” track, it was crossing a “yard” of track. The downtown passenger terminals are also marked.

Why and how did this ever happen? In Born Grown, Roy Stewart puts it this way: “Eagerness of city leaders to secure rail transportation was a paramount factor. Most of them were dreaming rather large dreams of making the city grow,” which it did – and it must be said that a large factor in that growth, in terms of both commerce and population, was the sudden influx of rail. Although it is said that Oklahoma City’s population by the end of Land Run Day was 10,000, if it was, it didn’t last long. Population change during the period discussed here was this:

| 1890 | 1900 | 1907 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | |

| Population | @4,000 | 9,900 | 32,452 | 36,205 | 91,295 | 185,389 |

| U.S. Rank | — | — | — | 87 | 80 | 43 |

In Oklahoma County: Heart of the Promised Land, Bob Blackburn elaborates:

In 1897 Oklahoma City looked like any other rural village of a few thousand people. The streets were unpaved and muddy much of the time. The central business district, confined to Grand and Main streets between the Santa Fe tracks and Robinson, had the rough appearance of a frontier town with wooden sidewalks and false fronts. * * * Despite this outward appearance, Oklahoma City was poised at a turning point in its brief history. In 1897 the young town still was locked in a stagnating five-year economic depression; by the end of 1898, the town again would be alive with the sounds of hammers and saws. There were several reasons for this transformation. One was an agricultural upturn after 1898; another was the arrival of a new generation of talented and energetic men. The real catalyst for the phoenix-like economic resurgence, however, proved to be the completion of the St. Louis and Oklahoma City Railroad [to become a part of the St. Louis & San Francisco Railroad].

Mr. Blackburn quotes an 1898 Oklahoma City resident as saying (when recalling the importance of the Frisco), “Most of all there was a new psychology, or shall I say the returning of the old psychology. The old hope, the old expectation, and the old spirit came back, and with redoubled strength.” Mr. Blackburn then says, “As a result of this rekindled fire, Oklahoma City entered an economic boom that tripled the population in just three years.”

So, while it may be true that, as Mr. Stewart says in Born Grown that …

They failed to visualize just what location of tracks, passenger and freight depots through the main part of town would do, as the city did grow and street traffic increased – even in the wagon and buggy days – which after 1910 the advent of motor traffic magnified.

… it likewise appears that without the rail, lots of people and an energetic economy wouldn’t have been a problem, either! In other words, without the tracks, you don’t get all this activity, either:

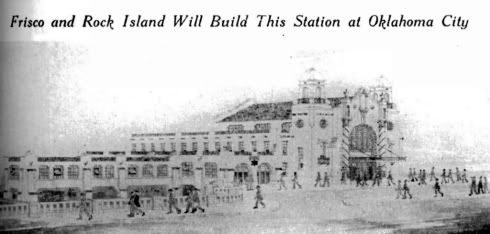

I Want My Space! Stewart notes that, “By 1911 the Chamber of Commerce had begun a twenty year fight before the State Corporation Commission and the Interstate Commerce Commission, to force the Rock Island and Frisco to remove its downtown trackage.” The years between 1911 to 1928 were fraught with administrative and court hearings, litigation, and, doubtless, a great deal of expense. In the end, and outside of either “side” being forced to do anything, an agreement was struck that the city would purchase back it’s earlier granted rights-of-way along what is now Couch Drive for the sum of $4,000,000, the tracks would be removed, civic improvements would be built in the same area, and Frisco and Rock Island would build a “common” passenger terminal, which is to say, a “Union Station.” I’ll expand this section later, but, for now, suffice it to quote from a February 20, 1929, Oklahoman article: ” ‘Twenty years of scrapping over a union station apparently was ended with the passage of the $4,000,000 bond issue which enabled the city to get the Rock Island and Frisco tracks out of the business district,’ said McKenzie [Oklahoma City Municipal Counselor]. ‘Everything now seems to be lovely.’ ” By August 11, 1930, concrete was being poured at the S. Harvey location for the new “Union Station” facility which would become the new location for the Rock Island and Frisco lines. If you want to research on your own, check out articles in the following Oklahoman issues: June 30, 1924; November 17, 1924; November 22, 1924; June 30, 1925; August 18, 1925; October 20, 1925 (which gives a nice historic overview of the issues); July 12, 1927; and November 26, 1929 … which ought to be enough to get you started!

Here are a few pics leading up to that event.

Next 2 pics, credit Oklahoma County: Heart of the Promised Land by Bob Blackburn (Windsor Publications 1982)

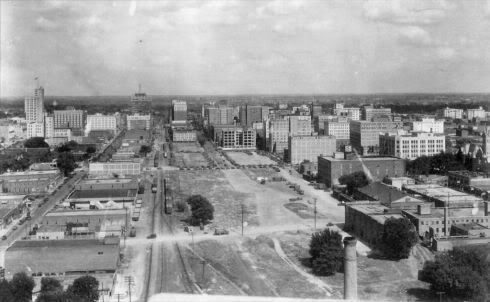

Looking South on Walker, 1929

Credit Oklahoma City: Statehood to 1930 by Terry L. Griffith (Arcadia Publishing 2000)

Note about the image below: Mr. Griffith says this pic was taken in 1925, but that can’t be right. Notice the completed Montgomery Wards building at the far right (more closely seen in the 2nd image, below). Its construction dates were 1929-1930. And, notice that a lot of track appears to have been removed in the former railroad right-of-way (compare the pic below with the one above) and that the 1931 1st National Bank and Ramsey Building are not yet in the skyline. I’m dating this image as having been taken in 1930.

A Cropped & Enlarged Selection From The Above

It wasn’t just the east/west tracks, though. Streets intersecting with the Santa Fe tracks were grade level crossings, as well, as shown in the pic below from Vanished Splendor III by Jim Edwards, Mitchell Oliphant, and Hal Ottaway (Abalache Book Shop Publishing Co. 1985):

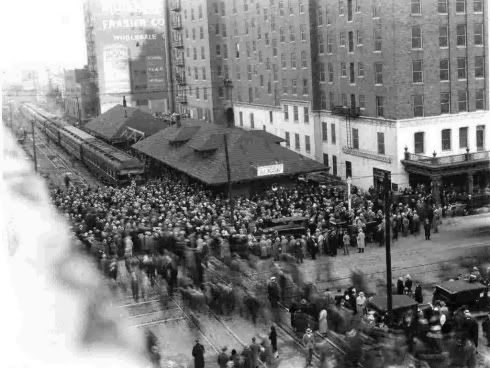

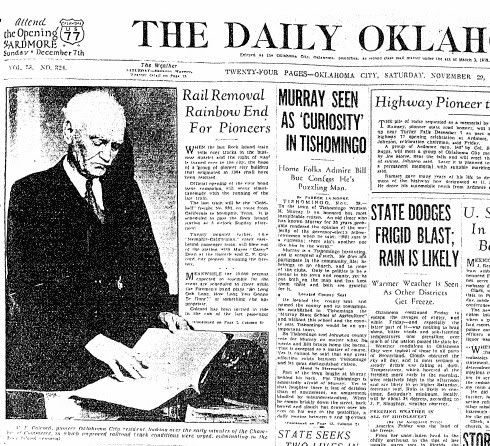

Colcord Gets A Ride. A long-time proponent of east/west track removal was former US Deputy Marshall, Oklahoma City pioneer, police chief, civic leader and businessman Charles F. Colcord. At the age of 71, he was on hand to take the last ride out of the Rock Island Depot on November 30, 1930, as you can see from the December 1, 1930, Oklahoman headline below:

Part of the article reads,

Completing the impossible, the “pioneers of 1930” broke down the “iron wall” through Oklahoma City late Sunday to push on toward their Utopia, a model civic center. The “wall” was the aged Rock Island line of rails which as divided the city since its foundation, and the “pioneers” the young business men of the city led by a veteran, C.F. Colcord, city builder. After the blare of the ceremony had settled down and darkness enveloped the city, light blazed along the old right of way as workmen for the company lifted the tracks and others began leveling the station relic. Their task is that of removing all signs of the railroad in 48 hours.

Before about 5,000 persons, all in a holiday spirit, the last passenger train over the line pulled in to the falling station and out with Walter C. Dean, mayor, at the throttle and Colcord, the guest of honor as he rode the first train into the city 41 years ago, wielding the fireman’s shovel. * * * As the train sped on its way, the junior chamber, Dean and Colcord broke ground for the city’s civic center which is planned for the old right of way.

Colcord was also the chairman of the committee which prevailed on the public to pass the $8,800,000 bond issue (there may have been 2 separte bond issues … I’m checking) used to finance this and related projects including elevation of the Santa Fe, new Santa Fe Depot subsidy, and the new Civic Center (City Hall, County Courthouse, Music Hall) which would replace the old tracks. More about that later.

For now, say goodbye to the Rock Island Depot just as Charles Colcord did almost sixty-seven (67) years ago!

From images provided by Norman Thompson in my Leo Sanders post

Credit Oklahoma City: Statehood To 1930 by Terry L. Griffith (Arcadia Publishing Co. 2000)

Union Station: New Kid On The Block. After all the fuss was over in late 1929, work proceeded promptly with the new Union Station located between Hudson and Harvey on SW 7th (then called Choctaw). Maybe it wasn’t built quite as advertised …

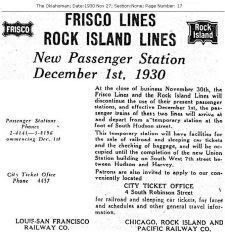

… but it did get promptly built and it was not bad at all. The 1st ad below, November 30, 1930, announces a “temporary” station while the new facility got built, and the 2nd, July 15, 1931, announces the new grand opening on the same day. Wikipedia says that Union Station had a “12-track, six-block-long passenger rail yard existed until circa 2000 when a scrapper removed all but two main track rail routes, currently operated by the Union Pacific and BNSF railroads, from the property. The right of way and former passenger rail handling facilities are scheduled to be removed and replaced by the relocation of Interstate 40.” The same article adds,

Passengers accessed the 12-track rail yard through subterranean tunnels via a gentle ramp from the grand waiting room. Mail and express were also routed under the tracks to the surface passenger platforms. Hudson and Harvey street traffic met the trains “at grade,” enabling easy passenger access and seamless exchange of time-sensitive mail and express freight between trucks and trains. Arterial traffic on Robinson and Walker streets flowed freely under rail yard underpasses built as an integral part of the station complex. Massive freight warehouses and material handling areas were located behind the passenger facilities.

See the full article for much greater detail. And, though I think that it’s a lost cause at this point in time, see the nomoron website and Oklahoma City Rail.org for Union Station advocacy groups that think otherwise.

|

|

Actual photos, inside and out, are shown below, in another section of this post.

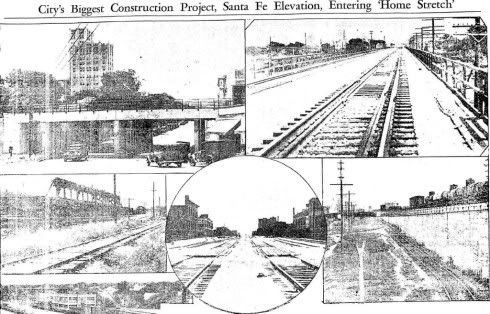

Santa Fe Station: Old Kid On The Block. With the change, Santa Fe would also get a new station. The 1900 version was razed in 1930, the downtown tracks were elevated so that traffic could pass underneath at various locations, and, eventually, a new depot would be completed later than expected, in 1934.

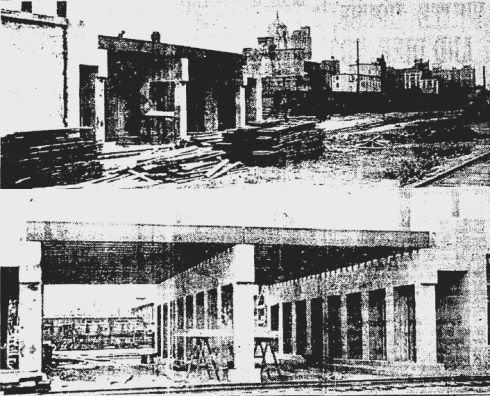

Leo Sanders was awarded the contract on elevation of the rails, just as they are today. On edit, I’d earlier posted 2 images which I thought had been part of the construction of the elevated rail through downtown, but on further study I see that they could not have been. The images were both dated in 1930 … but I see from the Oklahoman’s archives that Sanders did not start work on that project until 1931.

Replacing the earlier “good” images are a pair which aren’t as good, even if they are more accurate! The images are from the Oklahoman as work progressed.

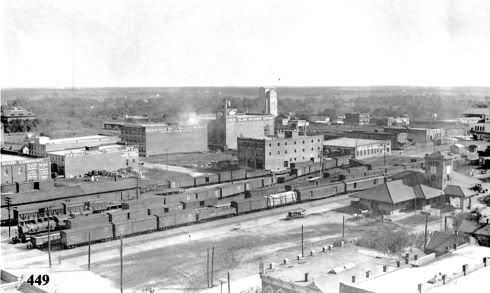

This is about 2 blocks south of the Santa Fe Depot

See the skyline in the background, top picture

July 23, 1933

The article reports that between Main and Reno, 6 tracks existed, which was the structure’s widest point.

As to the new station itself, as time went on. By early 1933 Santa Fe hadn’t started any work on the new depot and made hints that it might not build a new depot. The City suggested that the agreed-to subsidy would not need to be paid in such event. However, this rancor, too, went away and, even though 3 to 4 years late, in 1934, the new Santa Fe opened at last.

Sample Ad – November 27, 1934

Larger image not available

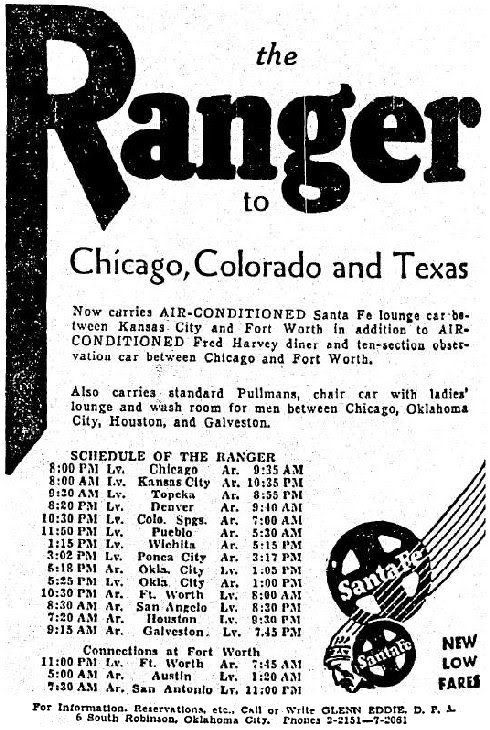

TRAINS AROUND THE TOWN. This section merely gives some typical fares and eye candy of the various trains we’d have seen during the 1930s to 1960s, more or less. With a few exceptions, they are not dated and, except as noted, are credited to Vintage Rail Pics (aka Whistle Stop Trains).

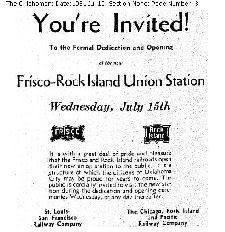

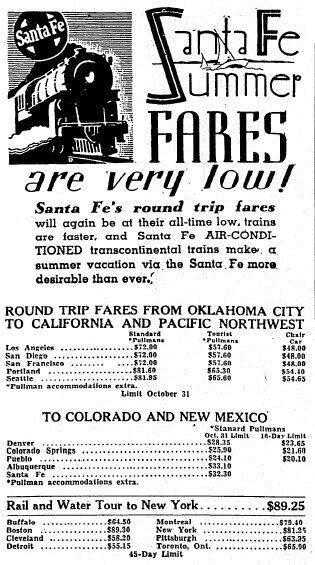

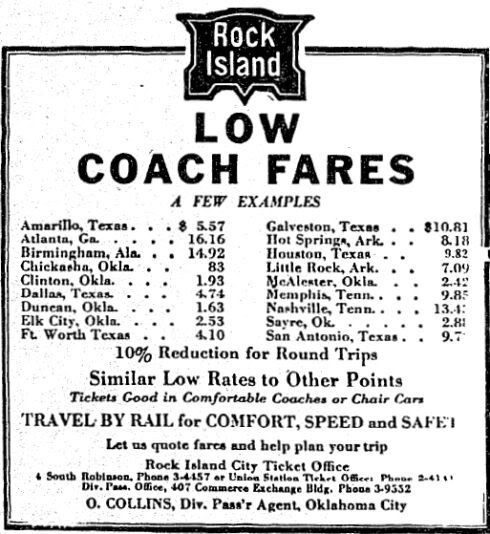

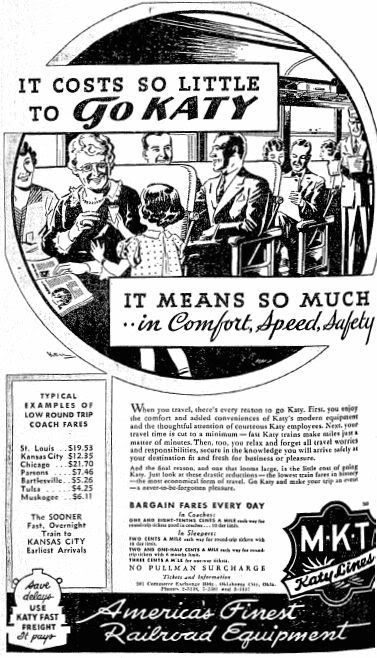

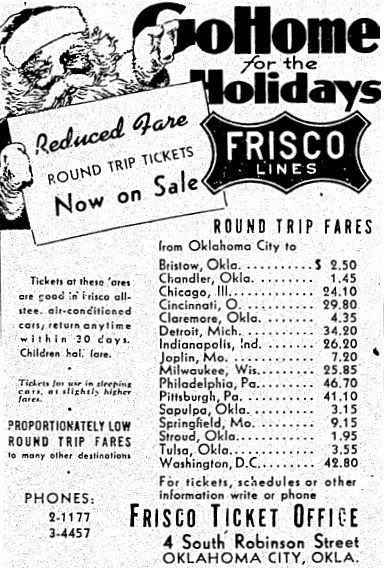

Exemplar Fares/Schedules in the 1930s. These Oklahoman ads show what it cost and some of the places you could go on passenger trains during the 1930s. Larger views are not available.

Rock Island Ad, March 1934

Katy Ad, August 1934

Frisco Ad, December 1936

Pics of Trains & Tracks. Now, for a “walkabout” of trains and places you could see way back when. Some weren’t taken in Oklahoma City (as noted) but they could have been.

The following Frisco pics are from Springfield-Green County Library. Some are identified as being taken in Oklahoma City, and some are more generic, as noted.

Larger image not available

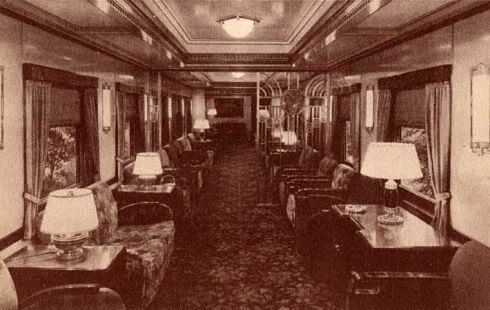

Ladies Lounge, 1939, Oklahoma City

Mens Lounge, 1939, Oklahoma City

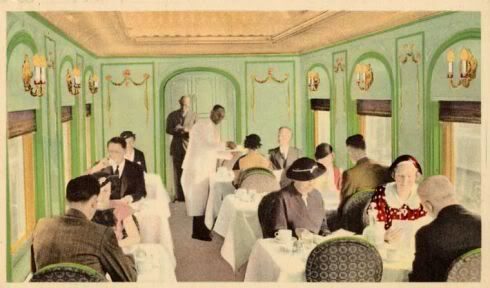

Frisco Dining Car (generic)

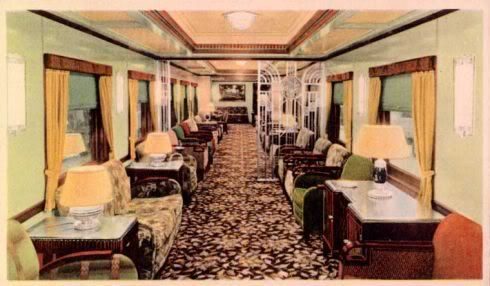

Frisco Meteor Lounge Car (generic)

Frisco Meteor Lounge Car (generic)

Frisco Snack Car (generic)

Santa Fe Downtown

From Vintage Rail Pics aka Whistle Stop Trains

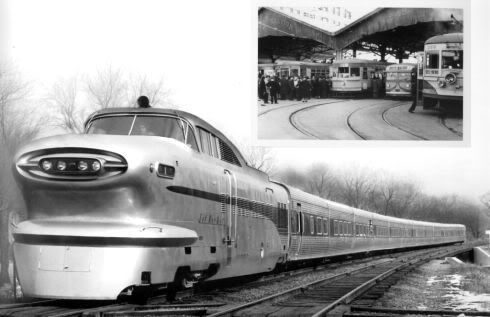

Rock Island Jet Rocket

Credit Images of History: The Oklahoman Collection by Bob Blackburn & Jim Argo (OHS 2005)

Frisco Westbound c. 1945

From Vintage Rail Pics (aka Whistle Stop Trains)

A Look Back At Union Station. Most of these images, too, are from From Vintage Rail Pics (aka Whistle Stop Trains). Some were personally taken by Ed Birch, as noted.

Vintage Rail Pics (aka Whistle Stop Trains)

Inside Union Station Pics Taken by Ed Birch Around 1967.

Ed Birch. As said in Okc Trains Part 1, Ed comes from a railroad family and has been around trains all his life. He worked for Rock Island in Oklahoma City until 1980 and took these “inside” pics in 1966-1967 before the passenger terminal closed. There, perhaps among other things, he was a ticket clerk in the last image shown below. Although reared in Goucester, “South Jersey,” he moved to Oklahoma City by choice in 1966, he having liked it here when earlier serving on military duty. He’s a delightful guy to talk with – you can meet him at Whistle Stop Trains on Britton Road.

Ed Birch. As said in Okc Trains Part 1, Ed comes from a railroad family and has been around trains all his life. He worked for Rock Island in Oklahoma City until 1980 and took these “inside” pics in 1966-1967 before the passenger terminal closed. There, perhaps among other things, he was a ticket clerk in the last image shown below. Although reared in Goucester, “South Jersey,” he moved to Oklahoma City by choice in 1966, he having liked it here when earlier serving on military duty. He’s a delightful guy to talk with – you can meet him at Whistle Stop Trains on Britton Road.

Santa Fe Downton

Credit Historic Photos of Oklahoma City by Larry Johnson (Turner Publishing Co. 2007)

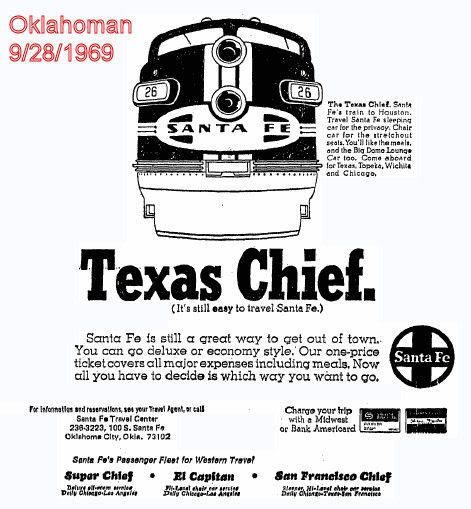

TRAINS WANE. The Katy ceased its Oklahoma passenger operations by July 1965, followed by the Frisco in May 1967, followed by the Rock Island six months later, leaving the Santa Fe’s Texas Chief as Oklahoma City’s only surviving passenger train. The other two were Santa Fe’s “The Tulsan” between Tulsa and Kansas City and the “San Francisco Chief” which passed through Woodward and Alva on its runs between Kansas City and the San Francisco area. Statewide, an April 20, 1970, Oklahoman article’s headline was, “Passenger Trains Fading Fast.” It said, “Of 70 passenger trains that ran through Oklahoma in the golden years of railroading, only three remain. The thread that holds even these three trains on the rails stretches thin; they may disappear soon.” “The city had as many as 50 passenger trains a day during the period during and just after World War II,” the article says. A “50 Years Ago Today” item in the November 10, 1967, Oklahoman said, “50 Years Ago – During the year 1917 there were as many as 10 Santa Fe railroad passenger trains through Oklahoma City daily, 16 Frisco, 10 Rock Island, eight Katy and four Fort Smith & Western.” For further reading, see the March 10, 1968, Oklahoman, page 19, “Train Whistle Ever More Lonely”, and the May 9, 1965, article, “Trains Don’t Stop Any More.”

As for Santa Fe, its passenger service remained in operation here until it opted into the National Railroad Passenger Corporation in April 1971, discussed below. One of Santa Fe’s latter day ads must have been the one below:

Santa Fe’s run in Oklahoma City as a passenger carrier ended at the end of April 1971, even though the route was continued on May 1, 1971, as part of the US government’s new “Railpax” system.

According to this Wikipedia article,

Under the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970, Congress created the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (NRPC) to subsidize and oversee the operation of intercity passenger trains. The Act provided that

- Any railroad operating intercity passenger service could contract with the NRPC, thereby joining the national system.

- Participating railroads bought into the NRPC using a formula based on their recent intercity passenger losses. The purchase price could be satisfied either by cash or rolling stock; in exchange, the railroads received NRPC common stock.

Any participating railroad was freed of the obligation to operate intercity passenger service after May 1, 1971, except for those services chosen by the Department of Transportation as part of a “basic system” of service and paid for by NRPC using its federal funds.

- Railroads that chose not to join the NRPC system were required to continue operating their existing passenger service until 1975 and thenceforth had to pursue the customary Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) approval process for any discontinuance or alteration to the service.

The NRPC was and is a quasi-public organization with 100% of preferred stock owned by the United States. An April 20, 1971, Oklahoman article reported that the Santa Fe Railway had joined the federally backed National Railroad Passenger Corporation (then known as Railpax, later renamed Amtrak). By doing so, Tulsa lost its route to Kansas City since that route was not on the Railpax list, but the Texas Chief route between Chicago and Houston (with stops at Kansas City, Ponca City, Perry, Oklahoma City, Norman, Purcell and Ardmore) remained open as Oklahoma’s last passenger rail service. Santa Fe Railroad initially allowed that Railpax use the former “name” of “Texas Chief” but, opining that Railpax wasn’t living up to Santa Fe standards, withdrew that permission in 1974 and the route was renamed as the “Lone Star.” The first “Amtrak” train pulled into Oklahoma City on May 1, 1971, “right on the dot” according to a May 2, 1971, Oklahoman article. With the advent of Amtrak service, stops were no longer made at Newkirk, Guthrie, Pauls Valley or Marietta, although stops in Ponca City, Perry, Norman, Purcell and Ardmore, as well as in Oklahoma City. The article said that, “Under Amtrak, it will stop at Union Station to make better connections with other Amtrak trains,” but that makes no present sense to me since no other passenger service existed in Oklahoma City at the time. Maybe that was a mistake in the article, I don’t know.

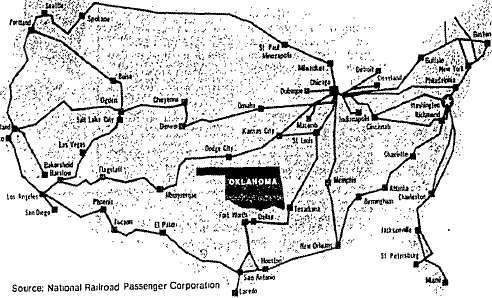

In any event, Federal spending cutbacks were in full swing in the late 1970s and the Lone Star route was reportedly one of Amtrak’s biggest money losers, according to a July 29, 1979, Oklahoman article. 1977 federal legislation mandated that the National Railroad Corporation (Amtrak) make adjustments to in its routes and to “live within its means,” according to a November 6, 1977, Oklahoman article. But, by as late as an August 22, 1979, Oklahoman article, Amtrak had not decided whether to keep the route. But, on October 1, 1979, Amtrak’s only Oklahoma route made its last “scheduled” run, even though it remained operational for a few more days due to pending litigation in US District Court in Wichita, according to an October 2, 1979, Oklahoman article. But, close down, it did and thereby making Oklahoma the largest of the four 48 contiguous states (Oklahoma, South Dakota, Maine and New Hampshire) not to have Amtrak service. The image below from a December 21, 1980, Oklahoman article gives the picture which would remain true for Oklahoma for two decades to come.

TWENTY YEARS WITHOUT A TRAIN. Did Oklahoma really care about the loss of passenger rail service? During the 20 years between 1979 and 1999 Oklahoma gave mixed signals. An 1980 initiative petition to overturn Oklahoma Attorney General’s Jan Eric Cartright’s legal opinion (that under the state Constitution money could not be given to a privately owned company, even though Amtrak was not a “for-profit” organization) to help subsidize such operations failed in a November 1980 statewide referendum – if passed, the referendum would have authorized the Legislature to raise taxes – the vote was a resounding, “NO,” 670,899 to 279,355. The vote was disheartening not only to the chagrin of Oklahoma rail enthusiasts but to those in Kansas and Missouri, as well, the article notes. The idea had been to reopen a route between Chicago, St. Louis, Springfield, Tulsa, Oklahoma City, and Houston. The December 21, 1980, Oklahoman article reported that even Amtrak had “lined up behind Oklahoma by appropriating its anticipated subsidy share and that Oklahoma was the only state to receive such an appropriation before officially requesting it.” The US congressional delegation hadn’t been of the same mind, either, with Sen. Henry Bellmon and Reps. Mike Synar and Jim Jones having earlier voted against a “freeze” that would have kept the Lone Star route open beyond its October 1, 1979, shutdown, a position apparently taken due to federal budget balancing perspectives, and notwithstanding the viewpoints of Reps. Glenn English and Mickey Edwards and Sen. David Boren.

Numerous ventures and adventures occurred in the two decades following which might have led to at least some renewed passenger rail service in Oklahoma. In December 1979, in response to a request by the Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce and supported by the Wichita Chamber, Amtrak agreed to perform a “feasability study” for a “demonstration train” for proposed service between Oklahoma City and Newton, Kansas. A November 25, 1979, Oklahoman article reported that, under the Amtrak Reorganization Act of 1979, that “demonstration routes” could be established between two major metropolitan areas that are not more than 200 miles apart. While the route between Oklahoma City and Newton was 199 miles, and while Newton, itself, did not qualify as such a metropolitan area, Wichita (which the route would pass through) did. Nothing came of that, however. By 1989, then Gov. Bellmon hadn’t changed his mind from his US Senator days. A September 6, 1989, Oklahoman reports him as saying that, “[We] have a lot better uses for our money” and that there is “no point in continuing to run them for nostalgic reasons.”

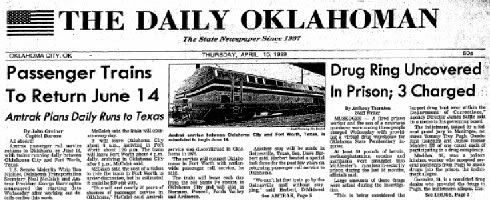

AMTRAK COMES BACK. As announced in the Oklahoman on April 15, 1999 (below), on June 19, 1999, Amtrak returned to Oklahoma but only in a limited way – the daily “Heartland Flyer” which leaves Oklahoma City for Ft. Worth in the morning and returns in the late afternoon. Oklahoma and Texas split the cost which is something like an annual $2 Million for each state. If I understand it correctly, the deal is that the states subsidize the route so that it does not operate at a loss. (For many other Okc/Amtrak articles, search the Journal Record archives by entering “Amtrak” in the search box there.)

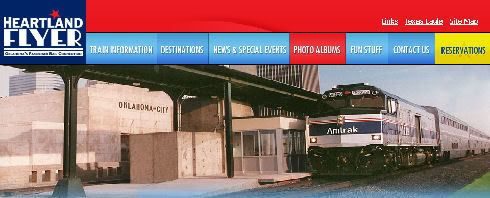

There’s a lot more about Amtrak in Trains Part 3 and Trains Part 3A. The Heartland Flyer has a fine website at www.heartlandflyer.com … click that link or the image below to get there.

By the way, on the Oklahoma side, the train clips along at 79 m.p.h., but it slows to 59 m.p.h. when it hits the Texas border. That’s because Oklahoma has spent some bucks upgrading the line for safety standards permitting the higher speeds but Texas has not. See Heartland Flyer’s Q & A web page.

| Train 821 | Train 822 |

| Leave Okc 8:25a | Leave Ft. Worth 5:25p |

| Leave Norman 8:49a | Leave Gainesville 6:41p |

| Leave Purcell 9:06a | Leave Ardmore 7:22p |

| Leave Pauls Valley 10:20a | Leave Pauls Valley 8:11p |

| Leave Ardmore 10:20a | Leave Purcell 8:36p |

| Leave Gainesville 11:01a | Leave Norman 8:53p |

| Arrive Ft. Worth 12:39p | Arrive Okc 9:39p |

SOME REMNANTS TODAY. A drive around town several days ago revealed the following remnants of the glory days gone by. I’ll add more later, but for now …

Union Station. While it still looks like a train depot, it does not act like one. Today, the old depot is owned by COTPA (Central Oklahoma Transportation and Parking Authority) which has at least some of its offices there. Don’t go down on a weekend wanting to take some “inside” pics (like I did), though, because it’s not open on Saturday or Sunday. Here’s what I saw …

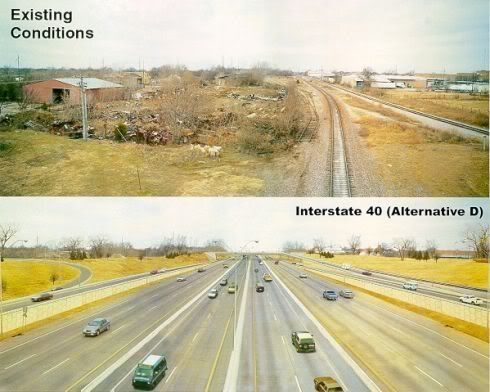

As for most if not all of the rail behind it (most has already been removed), it is set to be the location of the new I-40 Crosstown on which construction is well under way … even though there’s a lot left yet to do.

A couple of Oklahoma Department of Transportation’s images of what the road will look like are shown below (larger images not available).

Santa Fe Today. Today, Jim Brewer owns this facility and its future is in his hands … even though it is open as the Amtrak servicer early when the Amtrak heads south for Ft. Worth and in the evening when it returns. I’ll get some inside pics when I can to see if restoration of its original art deco premises are up to the mark.

The outside looks like this today:

IS THAT ALL THERE IS? Not exactly. Without a doubt, continued interest to extend Amtrak to Newton, Kansas, and/or Tulsa/Springfield exists. But, coming up with the bucks to make it effecient as well as carry Oklahoma’s share of the cost (like we do with the Heartland Flyer) is an entirely different matter. Here are a few items I found searching the web:

- Oklahoma City to Tulsa and/or KansasCity or St. Louis. Of course, there’s nothing new about talk of an Okc/Tulsa and/or points beyond Amtrak line. Aside from the cost factor of upgrading existing lines, even if the money were spent would the route be used if it would take 2-3 times longer to get there than it does a 1 1/2 hour trip up the turnpike? To be really high-speed, a new rail line straightening out lots of curves would likely be needed.

Still, the item is high on Oklahoma agendas. See this December 11, 2006, Journal Record article in which an Amtrak representative urged that studies be performed. The article provides a comprehensive list of problems and promise. Another article to read is in the April 16, 2007, Journal Record, discussing the legislative agendas of both Oklahoma City and Tulsa. There are many more. Just Google “Amtrak Tulsa” and you will find plenty.

- Oklahoma City Extention to Wichita/Newton/Kansas City. I found this AP story in the February 19, 2007, Kansan. The headline reads, “Group aims to expand Amtrak route into Wichita” and a bit of the text reads,

WICHITA (AP) — A group wants to bring Amtrak back to the state’s largest city, which hasn’t had passenger service since 1979. The Northern Flyer Alliance wants to speed up expansion of the Heartland Flyer route north from Oklahoma City to Wichita, Newton and Kansas City, Mo.

“I haven’t found one person yet who says that’s a crazy idea,” said Autumn Heithaus, the alliance’s executive director. Anyone wanting to catch an Amtrak train from the Wichita area must drive 20 miles north to Newton, and there is no service running south. That doesn’t sit well with 81-year-old Rosemary Terry, a member of the newly formed Northern Flyer Alliance. She would like to visit her daughter in Fort Worth, Texas, which is served by the Heartland Flyer route.

* * *

The expansion move also is getting support from Evan Stair of Norman, Okla., director of the Amtrak Extension Coalition.“This train should’ve operated through Wichita from day one,” he said. Oklahoma transportation officials, too, would like to see the route extended into Kansas. “It only stands to reason if it were connected to the north, the ridership would obviously be enhanced,” said Joe Kyle, manager of the rail programs division for the Oklahoma Department of Transportation.

To that I would add, “for what it’s worth.” It’s a nice idea, though.

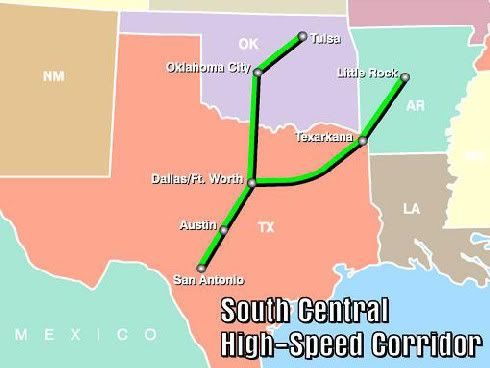

- South Central High Speed Corridor. I found the item below at the Federal Department of Transportation website. This idea/plan/concept/whatever-it-is has been “on the drawing board” in some way since 2004, but I’m clueless about what significance, if any, it has. If you’re curious, poke around here and if you find something useful, there you are!

- Another thing: During Oklahoma’s Centennial year (that’s this year if you’ve not been paying attention), Amtrak’s Heartland Flyer is running a cool special … pay for one adult ticket, get one free. Go to the Heartland Flyer website and scroll to the bottom of the page for more information. I’ve taken this trip with a group of friends about two years ago — we rented some neat rooms at a very nice Bed And Breakfast a little south of downtown called The Texas White House (they also chauffeured us around when needed and their meals and accommodations were outstanding) and we had a great time enjoying beautiful downtown Ft. Worth (which it really is, by the way), among other things. I heartily recommend the trip especially with a group of friends! The food’s not great (prepared sandwiches, mainly) but they do have a bar — not a great bar, but it’s a bar.

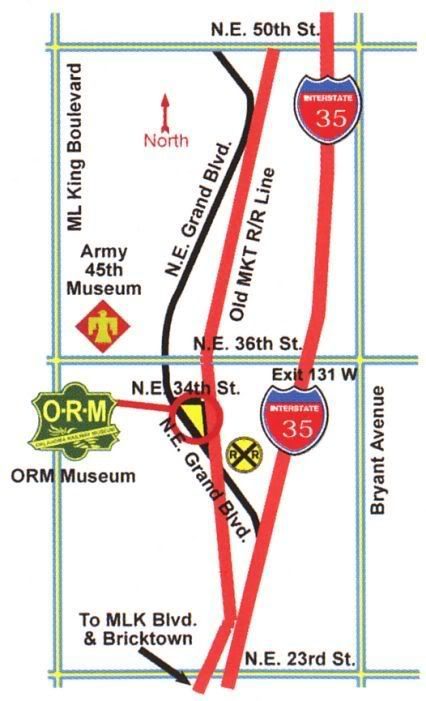

- And Another Good Thing: Okc’s Oklahoma Railway Museum. Located west of the old Katy tracks and just south of NE 36th Street (enter from ML King just south of NE 36th), the 30 year old Oklahoma Railway Museum provides a hands-on experience of looking at and being in the trains of old … here’s the map (larger image not available):

The museum is only open on Saturdays and it offers real and narrated train rides on occasion. See its website for more information.

Here’s a walk around the pastoral perimeter on August 29, 2007. Click on a small image for a larger view.

And there you have it! Okc Trains Part 2 is done … but … click on a link below for additional posts in this “Okc Trains & Trolleys” series … it turned out to be a much larger project than I thought it would be, in no small part due to the contributions of Dean Schirf, they mainly being in Trains 3 and Trains 3A.

Go To Trains Part 3 Go To Trains 3A Go To Trolleys 1