Oscar Jacobson Jacobson Foundation

Richard West National Museum of the American Indian

2008 Gala Silent Auction Inside the Ballroom

Not Your Ordinary Stomp Dance Live Auction Hello~Goodbye

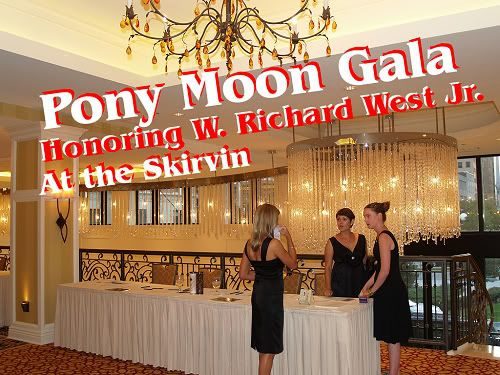

Last night, Saturday September 20, 2008, it was my pleasure to attend the Jacobson Foundation’s annual fund raiser and cultural event called the “Pony Moon Gala.” I’ve been with my wife once or twice before to similar events in Norman, but, to my knowledge, this was the 1st to be held in Oklahoma City, this one at the grand Skirvin Hilton Ballroom.

Ordinarily, the “boundaries” of my articles are Oklahoma City or County, per se, but with occasional lap-overs to the Oklahoma City metro. This is one of the latter combined with the former!

The event described below occurred at the Skirvin Hilton on September 20. The host of the event was the Jacobson Foundation in Norman and the celebrated guest honoree was a prominent state, national, and probably internationally known Native American person, W. Richard West Jr. However, before describing the festivities, some background is in order about Oscar Jacobson, the Jacobson Foundation, and W. Richard West, Jr.

ABOUT OSCAR JACOBSON. Born in Vastervik, Sweden, in 1882, Oscar Brousse Jacobson immigrated with his family to the United States in 1890, settling in Lindsborg, Kansas, where he attended public school and then Bethany College located in the same community. There, he studied art with internationally known artist Birger Sandzen and graduated in 1908. This August 29, 2007, Norman Transcript article by David Dary says,

During the next five years Jacobson taught at Minneapolis College of Art and Design and at the state college of Washington. During the first half of 1915, he studied at the Louvre in Paris. When he returned to the United States, he was hired as director of the School of Art and art museum at the University of Oklahoma in Norman.

| So, at age 32, he moved to Oklahoma to head the School of Fine Arts at the University of Oklahoma in Norman in which capacity he served until 1945. His home which came to be known as the “Jacobson House,” was built in 1917 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986. |  Larger image not available |

The Norman Transcript article continues (I’ve inserted ¶ symbols to show paragraph breaks in the original article to shorten its vertical presentation here):

In the late 1920s, something happened that forever changed Jacobson and the study of art. ¶ Less than 60 miles west of Norman at Anadarko, Sister Olivia Taylor, a Choctaw, began teaching art to Kiowa Indian students at a mission school operated by St. Patrick’s Catholic church.

Susie Peters, a woman working for the Indian agency in Anadarko, saw their art and was impressed. Peters organized an art club encouraging the students to memorialize the Kiowa culture in their drawings. She sent some of the drawings to Oscar Jacobson at OU in 1926. ¶ He was fascinated with what he saw. Their art was flat with ground planes of color. Jacobson invited the Indians to become special students at OU. Six Kiowa students – five boys and one girl — came to study with Jacobson. They were James Auchiah (1906-1975), Spencer Asah (1905/1910-1954), Jack Hokeah (1902-1969), Stephen Mopope (1898-1974), Monroe Tsatoke (1904-1937 who was also known as “Hunting Horse”) and Lois Smokey (1907-1981).

Smokey’s parents rented a large home in Norman where all of the Kiowa students lived while they studied at OU. ¶ The five boys became known as the “Kiowa Five.” While Lois Smokey’s art was included in nearly all of the early exhibits, she has not received the credit she deserves in the story of what became known as the Kiowa Five.

Jacobson provided the students with art supplies and studio space. He also provided them with a monthly stipend for their living expenses. He ignored suggestions that the Kiowa artists be taught to draw in a more European manner. ¶ During the 1920s and ’30s, Jacobson’s home became a meeting place for artists from Norman, Taos and Santa Fe who were shaking up the art world. At the same time Jacobson developed a market for Indian art that became known as the “Oklahoma School.”

In time, 31 Kiowa artists came to Norman to study under Jacobson. He circulated their watercolors widely throughout the United States. In 1928 their works were featured at the International Art Congress at Prague, Czechoslovakia. ¶ The Prague exhibit resulted in another showing in Paris. Newspapers in Paris, London and elsewhere praised the art. Their works received so much attention that it was next included in an exhibition of Southwest art in New York City. The Kiowa Five became celebrities in the art world.

Oscar Jacobson’s classes for Indian artists and those developed at the Santa Fe Indian School marked the beginning of the institutionalization of Indian painting. Jacobson lectured widely for the U.S. Park Service During the 1930s depression, he acted as a technical advisor for President Franklin Roosevelt’s Public Works of Art project in Oklahoma. ¶ Three Kiowa – Hokesh, Asah and Mopope – participated in the Intertribal Indian Ceremonies in New Mexico in 1930. Mopope, Auchish and Asah painted sixteen murals on the upper walls of the Anadarko Post Office in 1936 and ’37.

The works of the Kiowa Five and other Indians are today highly collectable. So are more than 500 landscape paintings that capture with simplicity the grandeur and dignity of the American West.

Jacobson, then about 63, retired from OU in 1945, but from his home on the northwest side of the campus he and his wife Jeanne d’ Ucel continued to encourage the development of Indian art. ¶ In 1951, the University honored Jacobson by naming the building housing the art museum for him. Today Jacobson Hall is the visitor’s center. Oscar B. Jacobson died Sept. 15, 1966 at age 84.”

(larger image not available)

THE JACOBSON FOUNDATION. The Jacobson Foundation was established in 1986 to preserve the home but, more, to honor and encourage “the legacy of Oscar Jacobson and his wife, Jeanne d’Ucel, while honoring the courage, talent, and achievement of the ‘Kiowa Five’ and all the Native American art students.” The foundation was responsible for securing the Jacobson House’s 1986 placement in the National Register of Historic Places. Noted Oklahoma historian, Arrell Morgan Gibson, one of my wife’s principal mentors in her own Native American educational journey, called the Oscar Jacobson legacy “a preservation imperative.”

| The Foundation operates the Jacobson House Native Art Center in the former residence of the Jacobsons. By bringing art exhibits, cultural activites, lectures, workshops and educational events to the public, the Jacobson House continues a tradition begun by the Jacobsons and their Native American student artists. Russell Tall Chief, Director, is observed in several photographs taken on September 20, below. |  Russell Tall Chief, Director (larger image not available) |

Additional information about the house, Jacobson, the Kiowa Five and much more is contained in the Jacobson House website. The collage below is assembled from a panoramic image of the Jacobson House interior at that website:

ABOUT W. RICHARD WEST. When talking about W. Richard West, it’s best to begin with his father, Walter Richard West Sr. (“Dick”), and his mother, Maribelle McCrea. Richard’s parents met at Bacone College, Muskogee, while Richard’s father was an art student there — the father would later chair the art department at Bacone from 1947 to 1970 and at Haskell Indian Junior College from 1970 to 1977. When Richard was 13, his dad, Dick, took him to New York see the Heye Collection. “It was more Indian material than I had ever seen in my life,” he says now, “almost overwhelming” — in particular the artifacts of his own Cheyenne ancestors. See this article in the March-April 2001 issue of Harvard Magazine. In that article, the author says:

His father counseled West and his brother, “You are Cheyenne, and don’t you ever forget that.” As a result, West speaks of a “bona-fide rootedness [in Cheyenne culture] that centers me.” His father also warned his sons that they would need higher education to succeed in the larger world. “We were pushed as fast as our little minds would run,” West says. “I think we have six or seven degrees between us.” He attended the University of Redlands, his mother’s alma mater, and found a mentor in the late Earl Cranston, Ph.D. ’31, an historian whom he credits with helping him gain admission to Harvard. It was in Cambridge, through family connections, that he met his future wife, Mary Ann Braden, a lawyer who is deputy assistant secretary of state for oceans and fisheries; the couple have two grown children.

Richard’s dad, Dick, is nicely described in this Oklahoma Historical Society article. Included in his father’s education was the University of Oklahoma where he was a student of Oscar Jacobson. In Richard’s remarks at the Skirvin on September 20, he remembered being in the Jacobson house when he was five years old.

Richard, also a lawyer, is further described in a very nice 2003 American Bar Association article which notes that:

West was born in San Bernardino, California on January 6, 1943, and grew up in Muskogee, Oklahoma. His father was Walter Richard West Sr., the Cheyenne master artist; his mother a music lover of Scottish ancestry. * * *

* * * West also kept up his interests in Indian history and culture, and in 1989 became involved in the efforts to create the National Museum of the American Indian. He served five years as coordinator and treasurer of the Native American Council of Regents of the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, gaining valuable insights into the contemporary Indian art world.

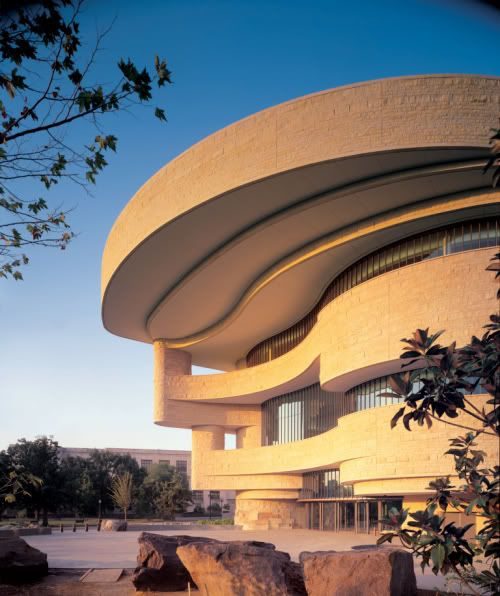

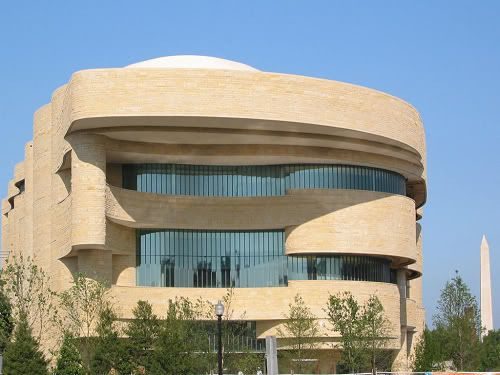

In 1990, West was named as the founding director of the National Museum of the American Indian. The Museum is a part of the Smithsonian Institution, and includes over 800,000 objects from the Heye collection. West says of the Museum, “One of our most serious commitments at the National Museum of the American Indian is to offer a counterbalance to the distortions engendered by the painfully long exclusion of Indian people from the interpretation of their own history and culture.” As director, West has been responsible for guiding the successful opening of the three facilities that comprise the Museum: the George Gustav Heye Center, which opened in New York City in 1994; the Cultural Resources Center, which opened in Suitland, Maryland in 2000; and the Mall Museum, which is scheduled to open on the last available site on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in 2004. West has also played a key role in guiding the philosophy of the “Fourth Museum,” a community outreach program giving millions of people worldwide the opportunity to experience the Museum’s collections, photo archives, exhibitions and public programs.

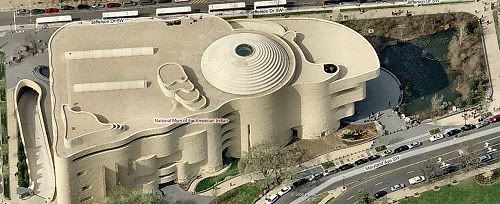

National Museum of the American Indian. West’s crowning glory was doubtless his work in establishing the National Museum of the American Indian, part of the Smithsonian, on the Mall in Washington, D.C. My wife attended the hugely glorious opening of that facility and I’ll post some of her photographs of that event later. Until then, a few images of the grounds are shown from general internet resources.

Below, Richard West is seen from within that facility with the U.S. Capitol in the background:

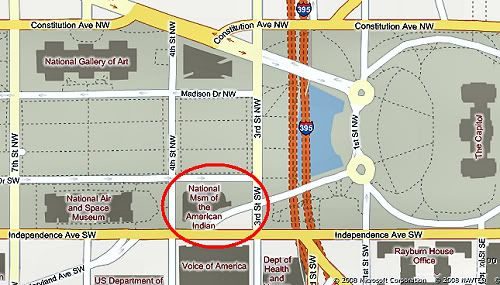

Map & Aerial Views from MS Maps Live

Looking West

Looking South

Looking North

Street Views of the National Museum of the American Indian

West retired from his position in 2007 in the midst of some controversy generated by the Washington Post concerning lavish and, it argued, unrelated-to-his-position expenditures. See this pair of articles: December 28, 2007 and February 10, 2008. One expenditure thought inappropriate by the Washington Post was associated with West’s retirement — “a gala dinner, the trust funds paid for the $37,000 catering bill, which included medallions of prime beef tenderloin seasoned with habanero chiles, and quail glazed with wild plum jam. Federally appropriated funds, however, were used to pay $30,585 for an eight-minute DVD biography of West, which was shown during the dinner and presented to him as a going-away present.”

As for Doug Dawg, I’m just glad that the Post made part of that cool video available for your viewing, regardless of how the newspaper characterized it in its captioning. It’s a very nice video clip.

Originally, I embedded that clip here but now the image below is only a link to the Washington Post video location … the code associated with the Post video was slowing down regular image loading here (particularly for users using MS IE Explorer, not so much for Firefox), so, now, click on the image to open the video in a new window or tab.

And, to be sure, the Washington Post’s viewpoints were quite obviously not troubling those present on September 20, 2008, in downtown Oklahoma City when Richard West, honoree, was enthusiastically revered and esteemed below.

PONY MOON GALA 2008. These are photographs that I took at the event on September 20. The first thing I should say is that I (once again) got to mooch off of my wife, Dr. Mary Jo Watson, Director of the School of Art and Art History of the University of Oklahoma. In Mary Jo’s academic circles, when I attend events with her many are surprised to learn that Dr. Watson even has a husband, I do that so infrequently. This occasion was one that I was glad that I didn’t miss!

The Silent Auction. As said in the beginning, a principal reason for the annual event is to raise funds for the Jacobson Foundation. Three means exist to accomplish that goal: (a) Tickets — the event cost $150 per person to attend; (b) the “Silent” auction — various supporters of the Jacobson Foundation donate works of art which are bid on “silently,” i.e., one writes down his/her bid on a piece of paper and sticks in a box or something, and the highest bidder wins the bidding; and (c) the ordinary auction at which oral competitive bidding occurs. The latter will be shown later in the article. Photos from the “Silent Auction” area follow:

Artist Tony Tiger (left, with coat & mustache)

Inside the Ballroom. Leaving the “Silent Auction” area, I took a few preliminary pics of the ballroom area and then the events which occurred, as follows:

Thanks to Dr. Watson, I was with her near the front

Left to right: Mary Jo Watson

Julie & Jackson Rushing – Jackson is Adkins Professor of the School of Art

Ghislain d’Humières, Director of the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art

After the meal, a few offered speaker remarks. I didn’t get them all,

but, of course, I did get Dr. Watson …

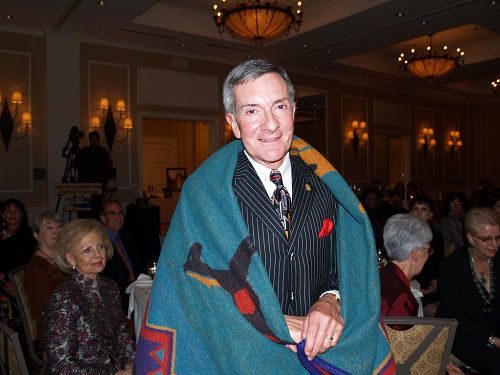

… and the honoree, Richard West …

a slide show of his father’s (Walter Richard West Sr.’s) art

was displayed on the large screen in the background

… who got the gift of a cool blanket …

Russell Tall Chief is in the center

… as well as a Native American serenade!

Here’s a much better view of Richard West

Founding Director Emeritus, Smithsonian Institution’s

National Museum of the American Indian

Not Your Ordinary Stomp Dance! If you’ve attended Native American “dance” events, you sort of know what to expect. Dancing tends toward the “traditional” and doesn’t change all that much.

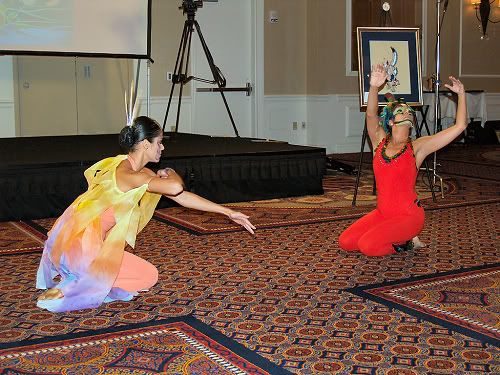

Not This Time! The dance performed at the gala was co-choreographed by Holly S. Tall Chief, ballet faculty member at the University of Oklahoma School of Dance, and Cheyla Clawson, Graduate Fellow in the School of Dance, both of them seen performing in the photographs shown below. Jacobson House’s publicity sheet about the dance reads, in part:

In honor of the West family, the gala will premiere an original dance composition inspired by the art of Dick West [Richard’s father and student of Oscar Jacobson].

More particularly, Holly S. Tall Chief describes the dance performed by her and Cheyla Clawson as folows:

The contemporary duet titled, “Green Rainbow” was performed to the music of Lunar Drive. The dance was inspired by paintings by master artist Walter Richard West Sr. (Cheyenne/Arapaho), and was performed in honor of his son, Richard West, Founding Emeritus Director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Tall Chief and Clawson based their dance on the particular painting “Water Serpent” by Walter Richard West, Sr. Holly’s movement represented the Thunderbird and Cheyla’s movement represented the Water Serpent, two important symbols in Native cosmology, representing the forces of good and evil. Costumes for the dance were created by Wendy Ponca (Osage), a textile artist who has worked for the Santa Fe Opera costume department and independently as a fashion designer.

As I said, it was not your average stomp dance! Have a look!

The following is my attempt to capture some

motion by combining the 2 above photos

The ladies were kind enough to pose after the performance — Hoo Ahh!

The “Live” Auction. After the above performance, several works of art (and a live buffalo) were auctioned off to the highest bidder. A few images follow …

Hi There, What’s New? After the auction, except for saying hello to friends, the event was done.

Betty Price, Retired Director of the Oklahoma Arts Council

Amber Sharples, Curator, Oklahoma Art Collection, State Capitol

Here’s a twirly-fingers to you, too, Amber Sharples! {grin} And that’s all I have to say about that!

That’s it … hope you enjoyed Doug Dawgz yet another scoop over the mainstream media! Hoo Ahh!