(Book-signing set for October 23 at Full Circle Books, Oklahoma City)

Norman Thompson generously sent me a whole CD full of Springlake images (more than 300) that had come his/his family’s way following the deaths of Roy Staton, and, later, his son, Marvin Staton. Roy Staton was the founder of Springlake in the 1920s, with beginnings around 1918 but not as the park it became. Except for the newspaper articles at the end, all of the images in this post have been supplied by Norman and I’ll not distill that most excellent contribution by posting Springlake images from other sources even though many others are available. I express my sincere gratitude and thanks for the allowance of posting these pics! After granting the privilege, Norman and his family donated the original images to the Oklahoma City Metropolitan Library System to allow for as wide a dissemination as possible for Okc history buffs to enjoy … now, that’s the kind of OKC guy that I’m talkin’ about! BIG TIME HAT’S OFF to Norman for setting the example for all of us to follow!

NOTE: You can see lots more of Norman’s Springlake pics than the 60 or so pics I’ve posted here at Norman’s Photobucket Springlake pics.

Update Note: OETA’s 2-minute Centennial video clip collection now includes a Springlake Video and it appears to include several of Norman’s pics which are posted here! Cool!

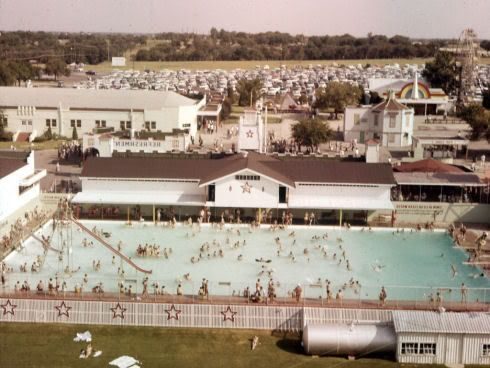

Admission to the park was free and rides and the pool were on a pay-as-you-go basis, i.e., if you just wanted to picnic by the lake, etc., there was no charge. Although the much-more-than-an-amusement-park no longer exists, its memory is honored by the presence of the Metrotech educational facility in its stead on the west side of Martin Luther King Boulevard and north of NE 38th Street and thereabouts and, as well, in the memory of some of us old geezers. An aerial image from the Oklahoma County Assessor’s website of the Metrotech Campus appears below (where the amphitheater, a car from the Big Dipper, and a few photos remain of the park):

A snippet from an article at www.okhistory.org gives this overview:

Oklahoma City boasted three amusement parks in the mid-twentieth century: Wedgewood, Springlake, and Frontier City. In 1924, after his spring-fed pond in northeast Oklahoma City had been open to swimming and picnicking for six years, Roy Staton built a swimming pool there. Later expanding his park, he bought many of the rides from the defunct Belle Isle Park, built a ballroom, and in 1929 added the Big Dipper roller coaster, a fixture in the park for almost fifty years. The height of Springlake’s popularity extended from the 1950s into the 1960s, and the park attracted top entertainers of the era including Johnny Cash, the Righteous Brothers, Roy Acuff, and Conway Twitty. A large riot that erupted in 1971 in the park, between whites and blacks, frightened away potential customers and hastened Springlake’s demise. A change of ownership, poor maintenance, and fire led to the park’s 1981 sale to the Oklahoma City Vo-Tech Board, which closed Springlake for good.

Roy Staton envisioned the park as being something very special, which it certainly came to be. An excellent article by William Boone, Springlake Park: An Oklahoma City Playground Remembered, appears at Volume 69 1991, No. 1, of the Chronicles of Oklahoma, pp. 4 ~ 25. That article give the history much more fully than this post will. Unfortunately, the article is not on-line, as far as I know, but I’ll quote from it as this post develops referring to it as William Boone, Springlake Park.

For now, have a gander at the cool pics which Norman consented that I publish here. The “easiest hard part” was selecting only a bit more than 60 of the 300+ that he kindly provided … nice kind of choice! Maybe I’ll add others later, but these 60+ pics should be enough eye candy for now. The “hardest hard part” was to remember the demise of the park and how that came to be. But, both the “good” and “sad” memories are real and part of Okc’s history.

Enjoy these images from days gone by!

Roy Staton

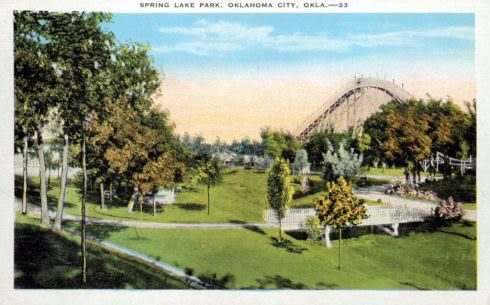

The Beginning Postcard and A Photo Celebrating the End

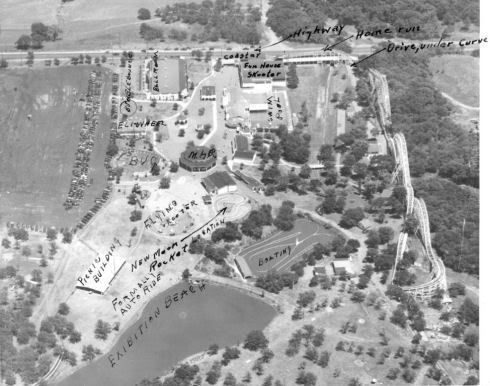

Aerial Views From Days Gone By

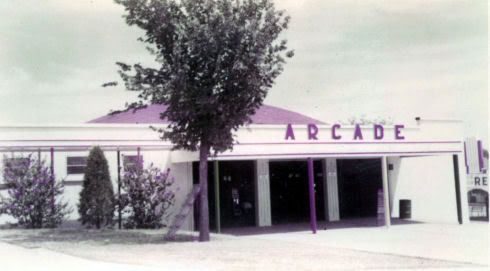

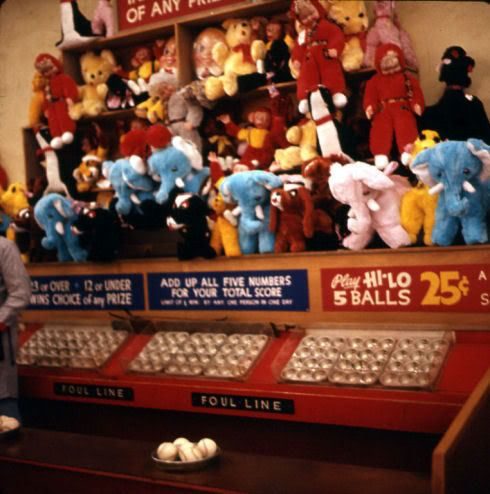

The Arcade

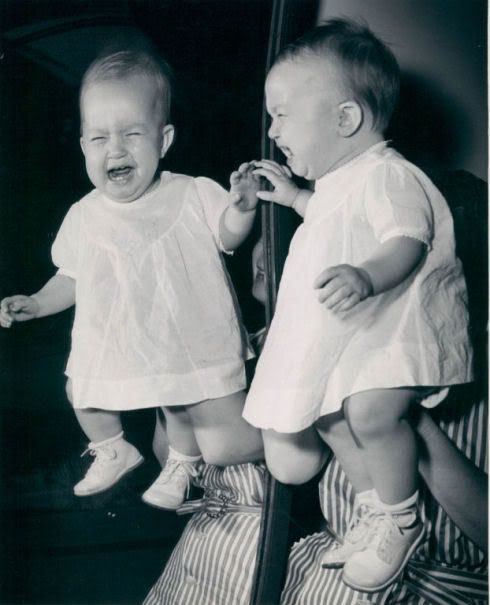

Babes In The Mirror

One Of The Free Picnic Areas

An Outdoor Picnic Area By The Lake

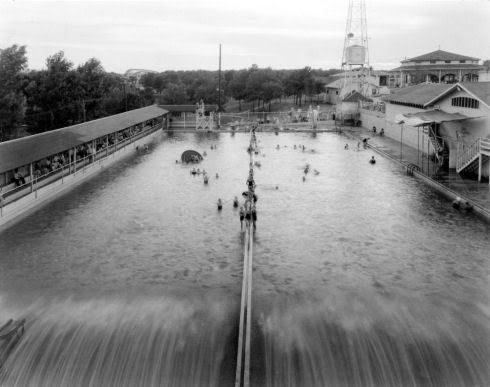

In The Pool … Little Girls …

… Hunks …

… Wanna Be Hunks …

… And Big Girls …

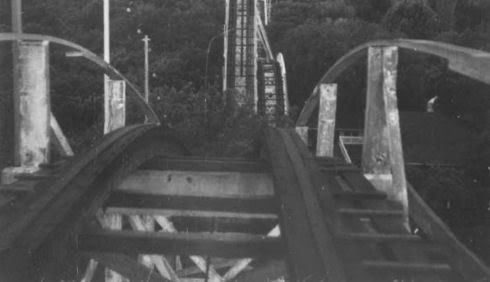

Of Course, There Was The BIG Dipper

Later, The Little Dipper Came To Be

Concerts & Famous People

According to William Boone, Springlake Park, the amphitheater held about 2,000 and hosted such performers as Roy Acuff, The Beach Boys, Johnny Cash, The New Christy Minstrels, Minnie Pearl, The Righteous Brothers, and Conway Twitty. Note that is not the same area as “The Pavilion” which was an indoor facility hosted 1940s (and perhaps earlier) patrons to dancing and “big bands” like Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, and Artie Shaw – that building became converted into the Fun House and other items, in the 1950s, I think.

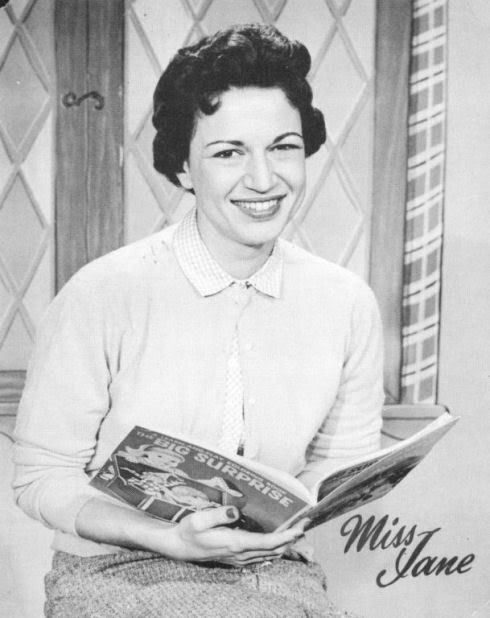

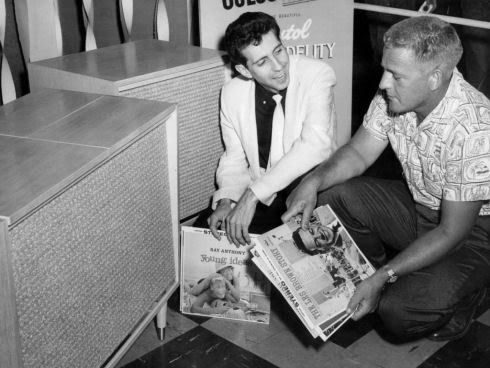

Local TV Personalities Were There

Miss Jane

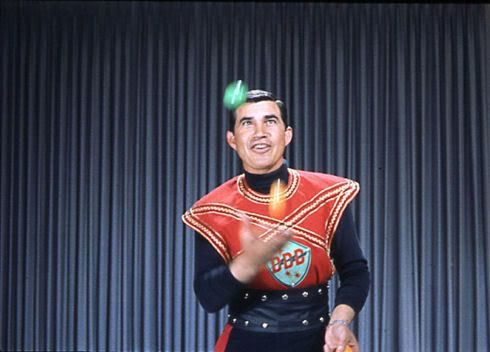

3-D Danny (Williams)

Foreman Scotty

Tom Paxton

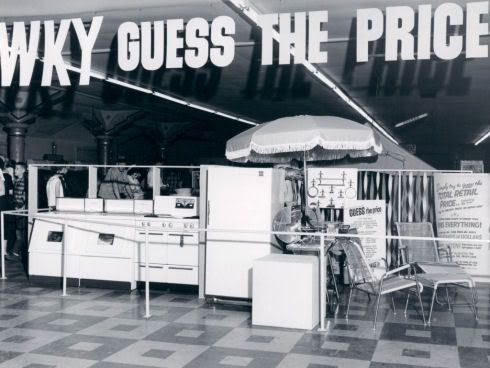

Contests

People Just Having Fun … Cooking, In This Example

For a time, parts of the park were open year-round, but, by the end of the 1940s, the park was open from Easter Sunday until Labor Day, opening with what it boasted was the state’s largest Easter Egg Hunt!

Bumper Cars

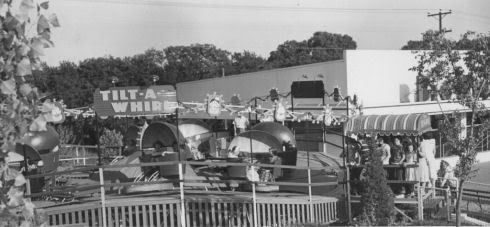

Tilt-A-Whirl

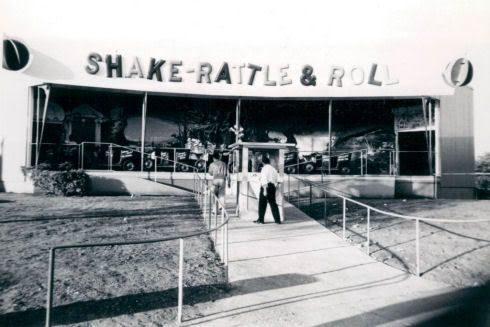

Shake Rattle & Roll

The Milky Way

Merry Go Round

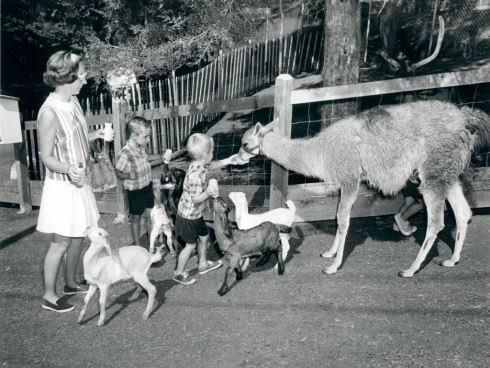

Petting Zoo

Ferris Wheel and Ride ‘N Laff

River Boat

The Lake

Super Chief

Sad to say, even after 1964, the swimming pool was for Whites only. That fact naturally led to protests, as rightly it should. William Boone, Springlake Park, describes the sad days which are part of our lore:

Springlake was affected not only by the legal an social changes of the time, but also by a particular change in the city’s demography. Once located in an all-white section of the city, the park figuratively became a white island in a black sea. Prior to the 1950s, Oklahoma City’s black residents lived mainly on the city’s near northeast side, south of Twenty-third Street. By the mid-1950s black families had moved northward into the immediate vicinity of Springlake park. Ruthie Forshee, a black woman residing on Springlake Drive in the mid-1950s, remembered watching the park’s Independence Day fireworks display from her yard. She was not welcome to participate in a celebration to commemorate her nation’s freedom.

No longer reluctant to enter the park after 1964 (with the passage of 1964 Civil Rights Act), blacks began to enjoy the same attractions white had enjoyed for decades. However, there remained an area of the park where blacks still were not welcome. Although many whites were willing to share the park’s midway with blacks, sharing the swimming pool was quite another matter. Clearly, Staton could not lawfully deny blacks access to the pool, but if he let blacks in, he risked losing many white patrons. Faced with a dilemma, his choice of action did not come easy.

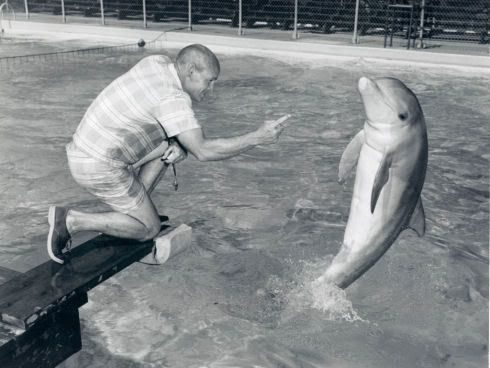

To avoid a clash between whites and blacks over the pool issue, Staton closed the pool to everyone except the members of an exclusive Aquatic Club, an evasive policy he soon abandoned. When Wedgewood Park opened its pool to everyone, Staton had little choice but to lift the membership requirement. Finally integrated, Springlake’s pool, open since 1924, closed forever after the 1967 season. It became a Sea-Acquarium, where dolphins frolicked in water once reserved for humans. The lost revenue from the swimming pool would be sorely missed in the years to come.

With racial integration of the swimming pool no longer an issue, Springlake’s management hoped that black and white patrons wold learn to enjoy the park together. Their hopes were in vain. After only a few years, the unwillingness of the races to mix peacefully spelled disaster for the park. The headlines of the city’s newspapers told the story.

Springlake’s gates swung open on April 11, 1971, admitting visitors to the park’s annual opening on Easter Sunday, just as they had done for the previous forty-five seasons. Park officials had no reason to believe that the crowd would be anything other than peaceful and orderly. According to one newspaper account, trouble began late in the evening when a rumor spread through the racially-mixed crowd that a white youth had been pushed by a black youth off the Big Dipper. The rumor triggered one of the worst civil disturbances in Oklahoma City’s history.

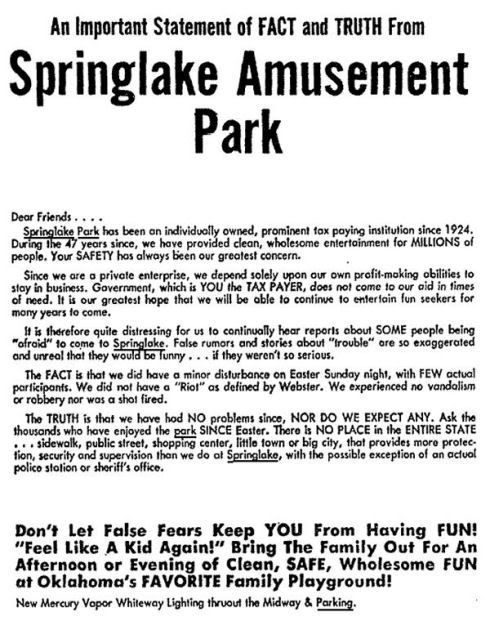

These being the 2 lone graphics in this post not supplied by Norman Thompson, it tells all that needs to be said or seen about once happy, then sad, days gone by — but see the note following the headlines graphic:

Since writing the original post a few days ago, it has come to my attention that The Oklahoman’s account, above, may have been seriously exaggerated and, perhaps, some parts imagined and not true. If I learn more about that possibility, I’ll certainly state what I learn here, but it certainly is true that our market contained only one newspaper at the time and that it was very powerful.

In June 1971, the following ad was run in The Oklahoman 3 times that I saw this morning (4/5/07), similar ads in June 1972 and July and August 1974, and perhaps other occasions that I did not notice.

Whether the Oklahoman article was true, false, or something in-between, its impact was done. One who was there on the night of the riot has been kind enough to write a note telling of her personal experience that night. Her report is this:

I was 21 years old and was working one of the games that night with another girl. Everything was great as usual, but then we heard people screaming and the next thing we knew, there were hundreds of people running everywhere, carrying boards, hammers, everything they could pick up that wasn’t nailed down. My co-worker and I were in shock. We tried to get our door down, and, of course it got stuck … we were terrified. Just at that moment a large black man jumped over our counter, never looked at us, shut down our door and went out the side door. The girl and I huddled as far back as possible, she with a claw hammer and me with a can of spray paint! LOL! We were going to do some damage to someone if they came in on us! LOL!

We stayed there until someone came to get us. I will never forget the sounds of those riot sirens as long as I live, nor will I ever forget the black man that closed our door for us. We were so scared … I dont think we even thanked him. The police led us out of the park through two lines of blacks they had lined up. Some of us girls were shaken and crying, some of us were just still trying to figure out what had happened. We were later told some white kids had pushed a black kid from the roller coaster and that it had set the blacks off. I still dont know the truth, to this day. I just knew that was the final blow for my beloved Springlake which I had been visiting since I was 5 years old. I saw so many stars there as a young girl and teen. I still miss it so. I still cant understand WHY people just cant get along. My favorite thing was the penny arcade. I miss it so much.

So, there you have the eye-witness account of Joan Ivers who, to this day, still doesn’t know the full story of what happened … but she knows that her happy days at Springlake had come to an end. She was not alone.

William Boone, Springlake Park notes that Mr. Staton developed health problems and spent the last few of his life in a nursing home. In 1977, the park was sold to Dale Thomas, but, after a 1981 $250,000 fire to the park’s old dance pavilion, then arcade building, that was all she wrote. As said in the beginning, the park was sold to the City in 1981. It is now the the premises of of a fine Metro-Tech education facility.