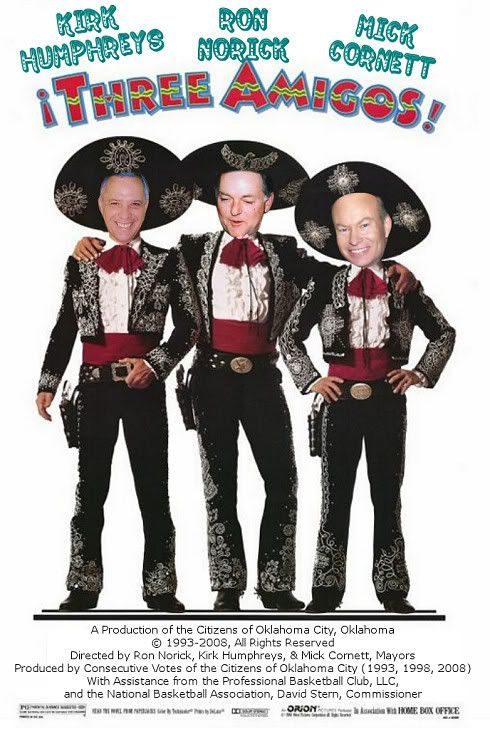

Or, “How Oklahoma City Became An NBA City”

Much of the internet press, certainly in Washington state and Seattle and even locally, focuses on who were the good, the bad, and the ugly, as to how such a far-fetched outcome (can you remember when George Shinn said, “Oklahoma where?“) eventually came to pass, and I’ve previously written some about that.

That’s not what this article is about — this article’s focus is on what this city did and how its leaders that laid the groundwork without which the July 2, 2008, outcome could not possibly have occurred.

Unless otherwise stated, the early-day MAPS history photos below are from and courtesy of OKC: 2nd Time Around by Steve Lackmeyer and Jack Money.

THE HISTORIC BACKDROP: Downtown Was Dead. So declared councilman I.G. Purser in 1988, and, he added, “We helped kill it.” His reference was to Oklahoma City’s initial major initiative about revitalizing a downtown that had already seen retail’s rush to suburban malls and all who witnessed the city’s generally decaying city core — that initiative being the bold Urban Renewal plan adopted in 1962, generally referred to as the “Pei Plan,” which was hoped to stem and turn that tide.

While a good bit got done during the time that Urban Renewal was really alive, including the Myriad Gardens and Convention Center, the construction of several new downtown buildings we enjoy today (e.g., Chase Tower, Mid-America Tower, Sandridge Tower (Kerr-McGee), Corporate Tower, Leadership Square, and Oklahoma Tower), and the beginnings of Neal Horton’s dreams for Bricktown, such development, for the most part, came to an effective end with the 1982 Oil Bust, the Penn Square Bank failure and the resulting domino effect in the banking community, eventually claiming as a victim even the state’s largest bank, the 1st National Bank in Oklahoma City. Purser’s 1988 statement was not far off the mark — by then downtown was almost solely a business sector which turned out the lights at the close of the business on Monday through Friday and didn’t turn them on again until Monday morning’s business resumed. In other words, downtown no longer possessed one of the principal marks of a “downtown” — a destination place for its citizens and others to go, other than for business, and just for fun.

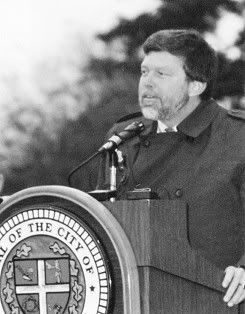

RON NORICK, the 1st and Foremost Amigo. Into this milieu, Ron Norick was elected mayor in 1987. I’m calling him “foremost” because it was his vision and gutsy determination that provided the backdrop for the others in his chain of leadership. By 1993, after having attempted several initiatives to lure out-of-state interests to the city and having learned the lay of the land, he opined, “When people hear of Oklahoma City, they just draw a blank. People just don’t have a clue about who we are. I just think that we have got to do something.”

RON NORICK, the 1st and Foremost Amigo. Into this milieu, Ron Norick was elected mayor in 1987. I’m calling him “foremost” because it was his vision and gutsy determination that provided the backdrop for the others in his chain of leadership. By 1993, after having attempted several initiatives to lure out-of-state interests to the city and having learned the lay of the land, he opined, “When people hear of Oklahoma City, they just draw a blank. People just don’t have a clue about who we are. I just think that we have got to do something.”

At this juncture in time, a bold proposal was formulated and promoted by Mayor Norick to resurrect downtown OKC from its doldrums, “Metropolitan Area Projects” (MAPS); if passed, the Mayor claimed it could reclaim downtown. His plan was “all or nothing” — voters would either accept or reject the entire proposal and nothing in between.

His plan included major upgrades to the Civic Center and Myriad Convention Center, a new library and learning center, a water canal and Triple-A baseball park in Bricktown, reshaping the North Canadian River to make it navigatable and add pedestrian trails on its banks between Meridian and MLK Jr. Avenues, and, yes, a sports arena capable of being the home to an NHL or NBA franchise was included. Rick Horrow, a Florida consultant astute in sports law and stadium financing, was engaged to assist in this effort. OKC: 2nd Time Around notes that one of his roles was to make speeches supporting the plan. I didn’t hear him speak “then” but I did in February 2008, and, trust me, this guy knows how to make a get-on-your feet speech!

His plan included major upgrades to the Civic Center and Myriad Convention Center, a new library and learning center, a water canal and Triple-A baseball park in Bricktown, reshaping the North Canadian River to make it navigatable and add pedestrian trails on its banks between Meridian and MLK Jr. Avenues, and, yes, a sports arena capable of being the home to an NHL or NBA franchise was included. Rick Horrow, a Florida consultant astute in sports law and stadium financing, was engaged to assist in this effort. OKC: 2nd Time Around notes that one of his roles was to make speeches supporting the plan. I didn’t hear him speak “then” but I did in February 2008, and, trust me, this guy knows how to make a get-on-your feet speech!

This brief article cannot properly tell that whole tale — for that, get a copy of the fine OKC: 2nd Time Around by Steve Lackmeyer and Jack Money which does so in great and vibrant detail.

Whether Norick’s grand vision would pass the voters’ muster was all but certain. Former Mayor Andy Coats had earlier championed a less comprehensive plan which would be financed by public bonds and the ballot was designed so that voters could cherry pick what they wanted and didn’t. On a few items, voters approved, but mostly they did not, and, as far as downtown capital improvements were concerned, that campaign accomplished little or nothing.

Some very influential city leaders were not all that impressed with Norick’s plan and lots of citizens weren’t either. The funding method was a one-penny sales tax lasting five years, designed to produce $238 million to finance the plan.

Click image for readable view

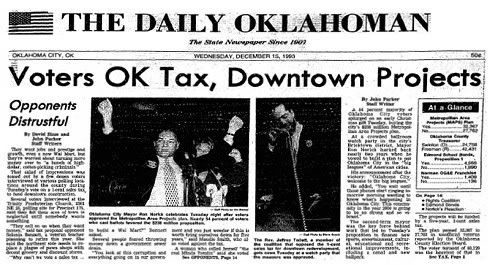

Mayor Norick’s MAPS plan was put to vote on December 14, 1993, as shown by the Oklahoman’s headlines that morning:

Click image for readable view

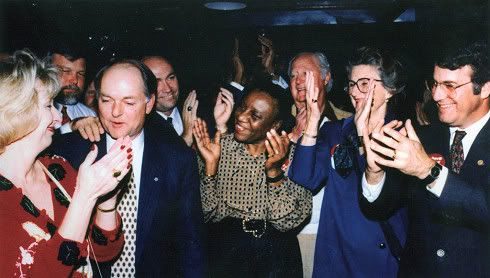

At the watch party at O’Briens in Bricktown

No Glum Faces Were To Be Seen

The Headlines on December 15

The referendum passed by a 54% /46% voter margin. The new 5 year penny sales tax was to fund major upgrades to the Civic Center and Myriad Convention Center, a new library and learning center, a Bricktown water canal and Triple-A baseball park, reshaping the North Canadian River to make it navigatible and add pedestrian trails between Meridian and MLK Jr. Avenues.

Slowness of visible progress and, eventually, cost overruns, dampened the enthusiasm of many. But, visible progress was demonstrated and the public was enthralled by the completion of the Bricktown Ballpark in April 1998 at which then outgoing Mayor Norick threw out the first ball … and a public figure who owned the triple-A team we know very well today made an address.

Slowness of visible progress and, eventually, cost overruns, dampened the enthusiasm of many. But, visible progress was demonstrated and the public was enthralled by the completion of the Bricktown Ballpark in April 1998 at which then outgoing Mayor Norick threw out the first ball … and a public figure who owned the triple-A team we know very well today made an address.

By that time, though, it was becoming evident that the revenue generated by the 5 year tax would not be enough to complete all projects at least as planned. The most obvious item in the MAPS package that could be eliminated was the NBA/NHL sports arena, and many in the community would have done that. At least one council member, Mark Schwartz, felt strongly that it would be a breach of the public’s trust were the citizens to be approached again for an extension of the tax.

KIRK HUMPHREYS, the 2nd Amigo. Ron Norick decided not to run for another term and seven mayoral candidates threw their hats into the ring. MAPS, not yet completed, was the election’s lightening rod. One candidate, Kirk Humphreys, campaigned on the premise of “completing MAPS right.” His principal opponent, Guy Liebermann, saw the matter quite differently.

KIRK HUMPHREYS, the 2nd Amigo. Ron Norick decided not to run for another term and seven mayoral candidates threw their hats into the ring. MAPS, not yet completed, was the election’s lightening rod. One candidate, Kirk Humphreys, campaigned on the premise of “completing MAPS right.” His principal opponent, Guy Liebermann, saw the matter quite differently.

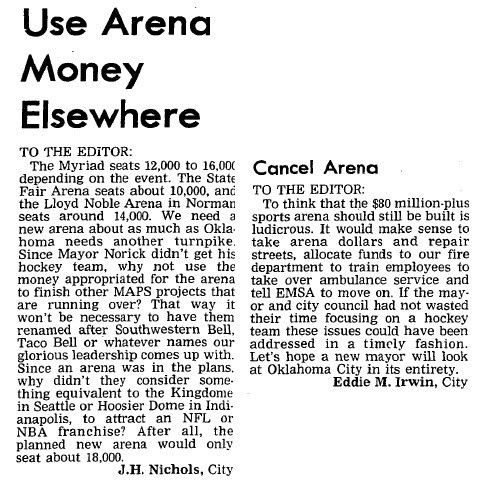

Click the images below for readable views

Letters to the Editor Show the Division

(Larger image not available)

Although Humphreys garnered 45% of the 1st vote, it wasn’t a majority so a runoff with Guy Liebermann followed on April 7, 1998. Liebermann won the support of several council members, Jack Cornett, Frances Lowrey, Ann Simank, and Frosty Peak, but Humphreys had the support of only one, Jerry Foshee. City Hall powers that “were” seemed aligned to support Lieberman and not Humphreys.

On April 7, the voters cast their preference. Humphreys received 67% of the vote and was elected mayor.

Click the article for a readable view

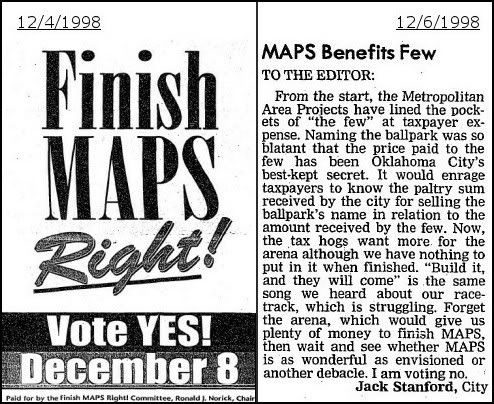

But, that was not the end … due to cost overruns and/or inaccurate tax collection projections, not enough money was present in the city’s coffers to complete maps as originally planned. The NBA/NHL sports arena received attention when Mayor Humphreys proposed to extend the MAPS penny sales tax by six months to “complete MAPS right.”

Opponents’ arguments then were not dissimilar to those presented in before the March 2008 vote to improve the Ford Center to bring it up to NBA standards and fund a practice facility for a then theoretically possible NBA franchise.

Click the article for a readable view

Dueling Items in December

(Larger image not available)

The Oklahoman reported the vote on December 9, 1998

Click the article for a readable view

The six-month sales tax extension was approved by 67.67% of Oklahoma City’s voters. The 581,000-square-foot arena was funded and on June 8, 2002, it opened its doors as the Ford Center in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Costing $87.7 million, it had the basics, not a lot of frills, and it was there.

After the 6-month MAPS extension, Mayor Humphreys and community leaders spearheaded yet another MAPS extension, this one called “MAPS For Kids,” a 7-year extension of the penny sales tax set to expire in December 2008. This $512 million project, coupled with a $180 million bond approved in the same election, provided $692 million in improvements to Oklahoma City’s public schools.

Larger image not available

MICK CORNETT, the 3rd Amigo. Time rolls along. Popular Mayor Humphreys did not run for re-election and in 2004 council member and former sportscaster Mick Cornett was elected mayor. None could then know what would transpire during the next four years of his mayoral tenure, even though we know very well, today, that this period is one of the most remarkable in Oklahoma City’s history. (I took this photo of the Mayor and his grandson on March 4, 2008.)

MICK CORNETT, the 3rd Amigo. Time rolls along. Popular Mayor Humphreys did not run for re-election and in 2004 council member and former sportscaster Mick Cornett was elected mayor. None could then know what would transpire during the next four years of his mayoral tenure, even though we know very well, today, that this period is one of the most remarkable in Oklahoma City’s history. (I took this photo of the Mayor and his grandson on March 4, 2008.)

It was during this mayor’s time that the prior efforts of Mayors Norick and Humphreys came to bear the gladness, the ecstacy, that Oklahoma City knows as this article is written. It was during this time that the Mayor met with David Stern, NBA Commissioner, looking for help in gaining a sports franchise for the city. Though nothing was in the cards at the time, that meeting planted a seed which later came to grow.

Everyone pretty much knows the rest — the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina, devastating to New Orleans, proved serendipitous for Oklahoma City. On September 9, 2005, NBA representatives toured the Ford Center with an eye to being the Hornets temporary home for the 2005-2006 season. Mayor Mick Cornett said, “If the games can’t be played in Louisiana for whatever reason, I’m anxious for Oklahoma City to have a chance to prove that it’s a major league market.” On September 21, the NBA announced that OKC would host the Hornets for the season.

On October 23, 2005, the Hornets played their 1st preseason game in the 19,163 capacity Ford Center before 14,475, losing to Denver; the 2nd preseason game, October 27, is a win over Houston with 15,063 in attendance. During regular season, 36 regular season games in OKC averaged 18,718, 9th in NBA, with 18 sellouts, and OKC wowed the national media with its support. Several writers opined that the Hornets should remain in OKC while the city reveled in a team that was 38-44 during the season. New Orleans not being ready for the team, a second season occurred at the Ford Center and the city continued its strong support for a team it knew was leaving at the end of the season — average attendance was 17,954 with 12 sellouts in OKC’s 35 games.

On October 23, 2005, the Hornets played their 1st preseason game in the 19,163 capacity Ford Center before 14,475, losing to Denver; the 2nd preseason game, October 27, is a win over Houston with 15,063 in attendance. During regular season, 36 regular season games in OKC averaged 18,718, 9th in NBA, with 18 sellouts, and OKC wowed the national media with its support. Several writers opined that the Hornets should remain in OKC while the city reveled in a team that was 38-44 during the season. New Orleans not being ready for the team, a second season occurred at the Ford Center and the city continued its strong support for a team it knew was leaving at the end of the season — average attendance was 17,954 with 12 sellouts in OKC’s 35 games.

During this time, Hornets owner George Shinn’s attraction to Oklahoma City as a permanent home for the team became clear, but that was not to be. Reports of a sale to local owners of a majority interest in the Hornets proved false. Instead, those local owners who we know as the Professional Basketball Club, LLC., purchased the Seattle SuperSonics from Howard Schultz in July 2006. (Ford Center pics taken by me at a pair of games.)

During this time, Hornets owner George Shinn’s attraction to Oklahoma City as a permanent home for the team became clear, but that was not to be. Reports of a sale to local owners of a majority interest in the Hornets proved false. Instead, those local owners who we know as the Professional Basketball Club, LLC., purchased the Seattle SuperSonics from Howard Schultz in July 2006. (Ford Center pics taken by me at a pair of games.)

And, during that time, Oklahoma City was again the beneficiary of serendipity — this time it was not a natural disaster but a political one as implosions of local politics in Seattle and Washington state played into Oklahoma City’s hands. The Professional Basketball Club fared no better than Howard Schultz had in his own attempts to obtain a new arena for the Sonics and after PBC’s October 31, 2007, deadline passed by with no arrangement struck for a new arena, PBC filed with the NBA to relocate the franchise to Oklahoma City.

And, during that time, Oklahoma City was again the beneficiary of serendipity — this time it was not a natural disaster but a political one as implosions of local politics in Seattle and Washington state played into Oklahoma City’s hands. The Professional Basketball Club fared no better than Howard Schultz had in his own attempts to obtain a new arena for the Sonics and after PBC’s October 31, 2007, deadline passed by with no arrangement struck for a new arena, PBC filed with the NBA to relocate the franchise to Oklahoma City.

Oklahoma City was born on April 22, 1889, by thousands of opportunists in the 1889 Land Run. Mayor Cornett more than matched our opportunistic ancestors and seized the moment by spearheading a blitz-like referendum to be put to the voters of Oklahoma City, a 12 or 15 month extension of the MAPS for Kids penny tax set to expire in December 2008, the purpose being to pump $121.6 million into the arena to dress it up and expand it to what is needed for it to be for a world-class professional basketball arena and to provide a training facility if an NBA team contracted to move here.

The Greater Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce handled the “Major League City” campaign. See this Cafe do Brazil meeting, this one at Toby Keith’s, for example. Rick Horrow, shown here at a Chamber “Breaking Through” luncheon, pumped up the more-than-willing audience one more time. (Photo taken by me on February 28, 2008.)

The Greater Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce handled the “Major League City” campaign. See this Cafe do Brazil meeting, this one at Toby Keith’s, for example. Rick Horrow, shown here at a Chamber “Breaking Through” luncheon, pumped up the more-than-willing audience one more time. (Photo taken by me on February 28, 2008.)

The vote was on March 4, 2008, and we know the results … out of the 72,413 votes cast, 62% said, “YES!”:

An agreement was entered into with PBC for the franchise to move here after the 2010 completion of its lease in Seattle. After an NBA Relocation Committee’s subcommittee visited Oklahoma City and expressed its robust satisfaction with what they saw, the NBA Board of Governors followed suit on April 18, 2008:

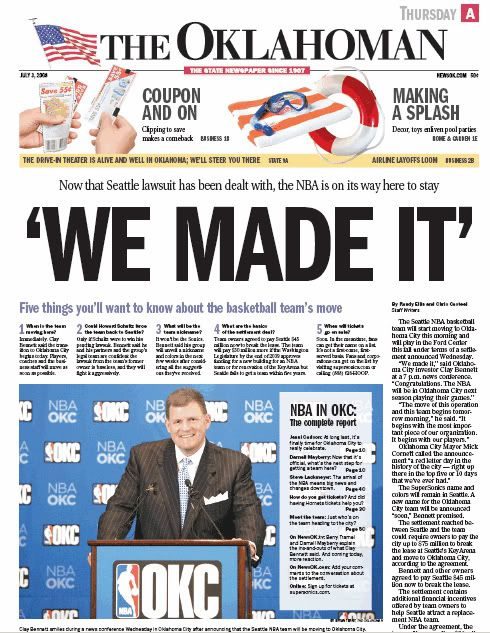

And, last week, on July 2, the date set for decision in City of Seattle v. Professional Basketball Club, LLC, a settlement was reached which sent the franchise packing to Oklahoma City on the next day.

As Clay Bennett said in a July 2, 2008, press conference,

He was probably not thinking at that moment of the efforts of Oklahoma City’s Three Amigos that led to that most excellent moment. But, I did and do. Without the passing of the leadership baton from Mayor Norick to another worthy Mayor Humphreys and then to Mayor Cornett who finished making the dream come true, and without our own gutsy willingness to follow while they led us along this path, this time would not have come.

If it hadn’t been the Sonics franchise on July 2, it would be another at some later time. It is NOT happenstance that Oklahoma City has become the home of an NBA franchise. It is only happenstance that the team’s former home is Seattle. To these Three Amigos, and most especially to the pioneer, Ron Norick, Oklahoma City owes its unending thanks. As Berry Tramel correctly noted in the just linked Oklahoman article,

“Everybody should remember this was a fortuitous conversion fostered by incredible hard work and vision and inspiration,” [Rick] Horrow said. “Let [there] be no doubt that Ron Norick was the father of this work.”