| As was said by Ensign Pulver (Jack Lemmon) to Captain Morton (James Cagney) in the great 1955 movie, Mr. Roberts,“What’s this crud about no movie tonight?” … for those of you who’ve never heard of this excellent movie, it’s one I’d recommend you rent … a great flick staring Henry Fonda and the others just mentioned) … |  |

… that line might be rephrased in the context of the SuperSonics litigation to read, “What’s the no-hyperbole skinny about the Seattle Franchise possibly not moving to Oklahoma City?”

This post begins to explore the two federal court lawsuits pending in Seattle which are attempts to tell Oklahoma City, “No movie tonight!” By no means definitive, this article attempts to discuss, in a rational manner, some of the issues involved, suggest some possible answers, and provide real documents which may bear upon them which you can assess for yourself. I’m not including the class-action season ticket holder lawsuit here since it is not deserving of further mention. I’m taking the Schultz lawsuit first and will then get to Seattle’s case.

To track the City of Seattle lawsuit at the Federal Court website, click here.

To track the Schultz lawsuit at the Federal Court website, click here.

First, a few documents, in html code for easy reading and loading. I’ll be adding others …

- Howard Schultz’s Federal Court Complaint. This is a verbatim copy of the complaint filed by The Basketball Club of Seattle, LLC v. Professional Basketball Club, LLC.

- Litigation Documents. This consists of various documents which have been filed as Exhibits in one or the other of the two lawsuits. Here, you will find relevant excerpts from the “Schultz/Bennett” contract and other documents.

- The July 18, 2006, “Side Letter”. This is the letter which Schultz’s Complaint relies on to maintain that PBC promised to keep the team(s) in the Seattle area though the term of the leases, if not beyond.

THE SCHULTZ LITIGATION. This section explores questions regarding the most recently filed lawsuit by The Basketball Club of Seattle, aka Howard Schultz. To go to a particular issue, click a link below.

- Standing to litigate

- Applicable substantive law

- Elements of fraud & burden of proof

- What’s A Constructive Trust?

- Retention of benefits

- Is the Contract enough for Schultz to win?

- What about the Side Letter?

- What about damages?

Issue 1: Does Schultz have legal “standing” to sue and in the manner that he has? A threshold question in any litigation is whether the party who commences it, usually called the “Plaintiff,” has authority to bring it in the first place. Howard Schultz is not, per se, the plaintiff in this litigation — The Basketball Club of Seattle, LLC, is identified as the “nominal plaintiff,” while Canarsie Holdings LLC is identified as the “derivative plaintiff.” Paragraph 3 of the Complaint alleges that, “Derivative plaintiff Canarsie Holdings LLC is a limited liability company organized under the law of the State of Washington and is a member of BCOS. Howard Schultz is the sole member of Canarsie Holdings LLC.” Paragraph 6 of the Complaint says, “Plaintiff is bringing this action because BCOS is not able to do so, and an effort to cause BCOS to bring this action is not likely to succeed. BCOS has not been in operating mode since the sale of the Sonics to defendant was approved on August 21, 2006; BCOS is not able to reconstruct a decision-making process in a timely manner, given the need to file this lawsuit at this time; and BCOS currently does not have the financial resources to finance this litigation.” And, in paragraph 2 of “Requests for Relief,” the Complaint asks for “equitable relief, including but not limited to the imposition of a constructive trust from which defendant can be ordered to convey the Sonics to an honest buyer who desires to keep the Sonics in Seattle.”

These allegations prompt these questions: (a) Why is it that the “nominal plaintiff” is merely “nominal”; and (b) If the litigation succeeds, is a 3rd party, that being “an honest buyer who desires to keep the Sonics in Seattle,” not the real and intended beneficiary of the Schultz litigation?

Discussion

(a) When the SuperSonics sale was consummated on July 14, 2006, which sale was approved by the NBA on October 31 or November 1 of the same year, The Basketball Club of Seattle, LLC, owned the team. Ordinarily, in a legal action, an actual party to the transaction, or its assignee, or some 3rd party if a 3rd party beneficiary contract is involved, would have “legal standing” to commence litigation. The Complaint identifies Howard Schultz as the sole member of “Canarsie Holdings LLC,” the “derivative plaintiff,” and says that the company is a member of BCOS. The Complaint does not identify Canarsie Holdings LLC as being either the owner of or an assignee of BCOS, it merely says that, “BCOS is not able to do so, and an effort to cause BCOS to bring this action is not likely to succeed.”

Why is/was BCOS “not able” and why would “an effort to cause BCOS to bring this action” likely not succeed? These are threshold questions which need to be addressed in order for Schultz to be deemed to have “legal standing” … for him to be deemed to be a “real party in interest” … to commence any litigation on behalf of BCOS.

(b) Since the BCOS/PBC contract specifically excludes an interpretation that it was a 3rd party beneficiary contract (see ¶9.2 of the contract), but since the Complaint effectively contemplates that an unnamed 3rd party become the beneficiary of the litigation should it succeed, is the relief requested not an attempt under the contract to do indirectly that which is prohibited directly in the contract … effectively converting the contract into a 3rd party beneficiary contract, regardless of provisions in the agreement which would prevent any such interpretation? This query may have more to do with “contract interpretation” than it does with “legal standing,” but perhaps not — Schultz is quite evidently suing upon behalf of some unnamed interest which would commit to keeping the Sonics in the Seattle area and it’s difficult to see the litigation in any other way since he is not wanting to undo the contract so that he would be obligated the $350 Million he already received (and he makes no offer/tender to do so) – so, if Schultz wins, he keeps the $350 Million and someone else becomes the owner of the team. Would that 3rd party have any obligation to return the $350 Million (and other moneys expended by PBC since the contract was executed)? What would Schultz gain? What could he lose? Who would pay PBC for the purchase price and costs expended?

The relief requested by one who may be ostracized-in-Seattle would be what some might call, “A bird’s nest on the ground!” He gets to keep his over-priced sale proceeds, loses nothing, someone else gets to purchase the team (making it a double-sale) and Schultz regains local respect as a local hero!

Think about it and answer the question for yourself: Do you think that Schultz (by any other name) has standing to maintain this litigation?

Issue 2: Assuming that Schultz’s litigation survives any preliminary dismissal motions, what “substantive” law applies? Federal questions are not involved here — “diversity” jurisdiction where parties are located in different states is involved, and, in that context and doubtless, the law of the state of Washington provides the applicable “substantive” law (i.e., what it takes to make a case in fraud, as opposed to “procedural” law which would be governed by federal court) about which Schultz’s claim must be measured. About this, there should be no “issue” at all.

Issue 3: What are the general elements of an action based upon fraud, and what is the “burden of proof” under Washington state law in that regard, i.e., what does the plaintiff have to prove, and what level of evidence is required for the elements to be deemed proven?

Discussion

It must be said from the outset that this writer is an Oklahoma lawyer, and, in fact, one who has no expertise whatsoever when it comes to litigating civil actions based upon fraud, even in Oklahoma. That’s not what I do, professionally. That said, it’s not difficult to research Oklahoma case and statutory law through the Oklahoma State Court Network where all Oklahoma statutes and all published decisions are “on-line” to the general public and are fully searchable. Doing just a bit of that, it is readily ascertainable that in Oklahoma that a plaintiff’s claim for fraud must minimally prove the following, as stated in Gay v. Akin:

¶7 * * * The elements of common law fraud are: 1) a false material misrepresentation; 2) made as a positive assertion which is either known to be false, or made recklessly without knowledge of the truth; 3) with the intention that it be acted upon; and 4) which is relied upon by a party to one’s detriment.

In an earlier case, Miller v. Long, the Oklahoma Supreme Court said, quoting Hembree v. Douglas,

2. To constitute actionable fraud, it must be made to appear that (1) defendant made a material representation; (2) that it was false; (3) that when he made it he knew it was false or made it recklessly without knowledge of its truth, and as a positive assertion; (4) that he made it with intention that it would be acted upon by the plaintiff; (5) that plaintiff acted in reliance upon it; (6) that he thereby suffered injury; and (7) all of these facts must be proved with a reasonable degree of certainty. The absence of any of them would be fatal to recovery.

3. In this jurisdiction, where fraud is alleged in the procuring of a written instrument, the proof must sustain the allegations by a preponderance of the evidence so great as to overcome all opposing evidence and repeal all opposing presumptions of good faith.

Under contemporary Oklahoma law, a “clear and convincing” and not a “preponderance of evidence” standard of proof applies. See Rogers v. Meiser, as follows:

¶17 The elements of common law fraud are: 1) a false material misrepresentation, 2) made as a positive assertion which is either known to be false, or made recklessly without knowledge of the truth, 3) with the intention that it be acted upon, and 4) which is relied on by the other party to his/her own detriment. Gay v. Akin, 1988 OK 150, 766 P.2d 985, 989; D & H Co., Inc. v. Shultz, 1978 OK 71, 579 P.2d 821, 824; Ramsey v. Fowler, 1957 OK 61, 308 P.2d 654 Syllabus by the Court. Fraud is never presumed and it must be proved by clear and convincing evidence. [Emphasis supplied]

How does Oklahoma’s law compare with Washington’s? It is apparently much the same. Although an Oklahoma lawyer (or non-lawyer) is at a serious disadvantage in “knowing” what Washington law might be (since, unlike in Oklahoma, all published decisions made by the Washington appellate courts are not on-line and publicly accessible as they are here), I’m left to quote from this on-line lawyer web page for some information. There it is stated,

In Oregon and Washington, the term “fraud” has come to have a definite meaning through case law. Oregon law provides 9 elements that must be proved by “clear and convincing” evidence, a standard that is higher than the normal civil case standard of “preponderance of the evidence” and lower that the criminal standard of “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

* * *

Washington also has identified 9 almost identical elements of the cause of action for fraud. As the court in Pedersen v. Bibioff, 64 Wn. App. 710, 828 P.2d 1113 (1992) wrote at page 723,To sustain a finding of common law fraud, the trial court in most cases must make findings of fact as to each of the nine elements of fraud. Howell v. Kraft, 10 Wash. App. 266, 517 P.2d 203 (1973). Those elements generally are: (1) a representation of an existing fact, (2) its materiality, (3) its falsity, (4) the speaker’s knowledge of its falsity or ignorance of its truth, (5) his intent that it should be acted on by the person to whom it is made, (6) ignorance of its falsity on the part of the person to whom it is made, (7) the latter’s reliance on the truth of the representation, (8) his right to rely upon it, and (9) his consequent damage. See Turner v. Enders, 15 Wash .App. 875, 878, 552 P.2d 694 (1976).

In this Washington case, the court held,

There are two basic rules to be applied in all cases of fraud:

First: “Fraud is never presumed, but must be proved.” obbin v. Pacific Coast Coal Co., 25 Wn. (2d) 190.

Second: “Fraud must be proved by clear, satisfactory, and convincing evidence.” Hopper v. Williams, 27 Wn. (2d) 579. See also Harrington v. Richeson, 40 Wn. (2d) 557; Cheesman v. Sathre, 145 Wn. Dec. 176.

In their decision of this case, the Appeal Tribunal has made reference to an earlier Review Case (Docket No. A-25670, Review No. 3400 [Good, CD 120]) and quotes therefrom as follows:

“But fraud is applicable only when it can be proved by clear, cogent, and convincing evidence. This constitutes the highest degree of proof. Perhaps the record in this case would suffice to establish a ‘preponderance of the evidence,’ but, as stated above, somewhat more is here required. Having so concluded, Section 75 of the law is not applicable.”

The foregoing quotation correctly states the rule as regards the sufficiency of proof necessary to establish a case of fraud. (See Hopper v. Williams, 27 Wn. (2d) 579, supra.) The second sentence of the above quotation could perhaps be amended to include the words “in civil cases of fraud.”

Mind you, the above is not taken from a Washington Supreme Court decision, even if it cites to such cases. But, again, the State of Washington has not acted to make its published decisions “on line” to anyone who wants to read them, unlike Oklahoma which has done that for many years. Nonetheless, and taking the above as being representative of Washington law, it appears that in either jurisdiction (Oklahoma or Washington) it is necessary that (1) basically the same elements need to be established, (2) those elements must all be established by “clear and convincing evidence,” and (3) among other requirements, it must be plead and proved that damage occurred to the plaintiff who relied upon the false representations.

OK, OK! Too many words and “lawyer words,” at that! If you just want “sound bites” from internet web “experts” who are getting paid on ESPN or wherever for saying them and presume to know a heck of a lot of law even without perhaps having read and/or studied the relevant litigation documents and/or perhaps applicable law, that’s not a problem … read and believe whatever you will. But, maybe you want to actually think and reach your own conclusions. I’m taking this slow path, giving you real documents and real case law and, quite possibly, bore you to death in the process. But, if you stay with this, you will be better able to reasonably reach your own conclusions and have less need to rely upon the sound-bite approaches that are readily available elsewhere on-line. That’s your call.

Issue 4: What’s a “constructive trust” all about? Generally, a “constructive trust” is or can arise when the “legal” owner of property (the person whose name is on the title) holds or is deemed to hold title for another, that other being the “equitable” or “real” owner of the property. For example, in a transaction Buyer contracts with Seller to acquire property which, upon the happening of an event in the future, is to then be conveyed to a Third Party, Buyer would hold title as a constructive trustee for the benefit of the Third Party. An action to impose a constructive trust is an “equitable” proceeding, governed by principles of “equity.” Oklahoma case law has said that, “The holder of the legal title to lands will, in equity, be charged as trustee where it was acquired by fraud or under such circumstances as to render it inequitable for him to retain.” To establish a constructive trust, Oklahoma cases hold that the evidence must be “clear, unequivocal, and convincing” — for example, see this case as well as the one linked, above. Presumably, though I’ve not researched it, Washington law is not terribly dissimilar.

Discussion: One problem with a “constructive trust” theory, though, is that the contract between BCOS and PBC expressly disavows that it is a “3rd party beneficiary contract — one that creates actionable rights in favor of any 3rd person. Paragraph ¶9.2 of the purchase contract is named, “No Third-Party Beneficiaries,” and it reads, “This Agreement shall not confer any rights or remedies upon any Person other than the Parties, and their respective successors and permitted assigns, other than as specifically set forth herein.” As relates to the Schultz litigation, “others specifically set forth herein,” do not exist – there aren’t any.

Try looking at the situation differently — instead of Schultz suing to create a constructive trust the object of which was to vest Sonics’ ownership in some local group, instead, some 3rd party, e.g., Ballmer and his group, brought suit under the same theory. Could such a group succeed? Of course not, since the contract explicitly excludes such a construction. See this Oklahoma case, for example. If 3rd parties could not succeed in such a litigation attempt, it seems extremely remote that Schultz could effectively do indirectly what 3rd parties could not do directly.

Issue 5: Retention of Benefits — can Schultz have his cake and eat it too? Although some internet articles label Schultz’s litigation an attempt to “rescind” the BCOS/PBC agreement, strictly speaking, it is not. “Rescission,” as a cause of action, is an attempt to undo a contract, it does not involve an attempt to enforce one. When attempting “rescission,” a seller must ordinarily offer back the “consideration” to the buyer, e.g., $350 Million at the least in this case, as part of the litigation. In plain speech, if Schultz’s case was for rescission, he would need to pony up $350 Million, and, quite possibly, PBC’s expenses associated with its attempt to secure arena funding through the Legislature, and, maybe, operating losses incurred during the season just had. As an example, this Oklahoma case says, “Again, it is well settled that, if the complaining party has allowed a change to take place so as to modify the situation with reference to the property involved, or, if he retains benefits under the original or new contract, then rescission will not be declared.” In another case, the Oklahoma Supreme Court said, “But the contract may be so drawn as to make time the essence of it and provide for the termination of the contract upon the default complained of. In such case the court will rescind on certain conditions, one of which is that the party seeking rescission must restore or offer to restore all benefits he has received. Nelson v. Golden, 84 Okla. 29, 202 P. 308; Nicholson v. Roberts, 144 Okla. 116, 289 P. 331, and the offer must be unconditional.”

But, no, that’s not what Schultz wants to do. He wants to keep the $350 Million and be obligated for none of the legislative expense and/or operating losses. The heart of Schultz’s request for relief is this: “For equitable relief, including but not limited to the imposition of a constructive trust from which defendant can be ordered to convey the Sonics to an honest buyer who desires to keep the Sonics in Seattle.” The constructive trust he wants the court to establish would make an unnamed 3rd party the beneficiary of such a trust. In non-legal parlance, Schultz wants to have his cake and eat it, too.

Discussion. Aside from problems associated with 3rd party beneficiary provisions, already discussed, can Schultz actually do this — keep the money and force a sale to some third party? I’ve already identified my lack of expertise in this type of litigation, certainly Washington state law, but, that said, such an approach strikes me as “reaching” to the nth degree, so much so that it may well provide the fodder for a dismissal motion for “failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.” Certainly, one would reasonably suppose that Schultz’s attorneys will need to have some precedential cases which would authorize such a request under Washington law. We shall be waiting to see them.

Issue 6: Does the contract itself impose obligations on PBC to keep the team in Washington after October 31, 2007? Very clearly, the answer to this question is, “No.” The July 14, 2006, contract contain but one related promise, stated in ¶5.3 Puget Sound Area Lease, which creates an obligation on PBC as follows: “For a period of 12 months after the Closing Date, Buyer shall use good faith best efforts to negotiate an arena purchase, use or similar arrangement in the King, Pierce or Snohomish counties of Washington as a venue for the Teams’ games, to be used as a successor venue to KeyArena; provided, however, that the process described in this Section 5.3 and the entering into of any such arena lease, purchase, use or similar arrangement shall be at Buyer’s sole discretion.” The contract also states, under Article III, Representations and Warranties of Buyer, that, “Except for the representations and warranties contained in this Article III, Buyer makes no other representations or warranties, written or oral, statutory, express or implied. Seller acknowledges that except as expressly provided in this agreement, Buyer has not made, and Buyer hereby expressly disclaims and negates, and Seller hereby expressly waives, any representation or warranty, express or implied, at common law, by statute, or otherwise relating to, and Seller hereby expressly waives and relinquishes any and all rights, claims and causes of action against Buyer and its representatives in connection with the accuracy, completeness or materiality of, any information, data or other materials (written or oral) heretofore or simultaneously outside of this agreement furnished to Seller and its representatives by or on behalf of Buyer.” And, ¶9.3 Entire Agreements and Modification, states, ” This Agreement (including the exhibits hereto) constitutes the entire agreement between the Parties with respect to the subject matter hereof and supersedes any prior understandings, agreements, or representations by or between the Parties, written or oral, to the extent they relate in any way to the subject matter hereof. This Agreement may not be amended except by a written agreement executed by both Parties.

Discussion. A general rule of contract litigation is that oral and/or written statements which explain the meaning and/or intent of a contract are inadmissible to interpret a contract’s meaning if the contract, on its face, is clear and not ambiguous. Aside from the possibility that the phrase, “good faith efforts to negotiate,” etc., is not particularly defined, a fair reading of the contract does not disclose any other possible ambiguity. If an obligation is not contained in a contract, it is quite simply, not an obligation of the contract. Consider a simple real estate purchase contract which contains the obligations of a buyer and a seller. Perhaps the seller has some obligations to make various repairs or improvements. The Buyer would be hard-pressed to insist that the Seller perform repairs or improvements which were not specifically identified in the contract. That Schultz’s litigation involves so much more than a simple house sale and is receiving lots of local and national attention does not change these basic principles.

Assuming for the purpose of argument that oral or written statements were made by PBC before July 14, 2006, which obligated it to keep the Sonics in the 3-county area after October 31, 2007, any such statements would have been merged into the July 14 written contract, according to its ¶9.3 terms. Without more than the Contract, Schultz’s lawsuit would clearly fail.

Issue 7: Of what legal effect is the “Side Letter?” Given that the Contract contains no requirement that PBC that it keep the Sonics in Seattle after the initial 12 month period during which time PBC was obligated to “use good faith efforts to negotiate an arena purchase, use or similar arrangement” in a 3-county area “as a successor venue” to the Key (although the same provision also gives the discretion of entering into any such lease, etc., to PBC), any such additional requirement must come from somewhere other than the Contract itself. Hence, Schultz’s Complaint attempts to create such additional obligations via the July 18, 2006, “Side Letter.” In this, I’ll assume that the “Side Letter” contains clear and unambiguous statements such as, “PBC agrees that the Sonics will play all home games in an arena located in King, Pierce and/or Snohomish County, Washington” (even though, of course no such statements are in the actual letter).

Discussion. First, it is necessary to determine Schultz’s purpose in raising the “Side Letter” — is it an attempt to say that the Contract was “modified” by the letter’s terms, or is it an attempt to “explain” the Contract, itself? If the purpose is to modify the original Contract, ¶9.3 Entire Agreements and Modification must be complied with. A part of that paragraph reads, “This Agreement may not be amended except by a written agreement executed by both Parties.” Since the “Side Letter” was not signed by a representative of BCOS, it fails to “modify” the original Contract.

As for the latter purpose and as has already said, unless a contract is ambiguous, a general rule of contract litigation is that other evidence, written and/or oral, is not admissible to explain its meaning. Since the Contract is not ambiguous (at least, not to me), the “Side Letter” should be ineffective and not admissible for ascertaining the provisions of the Contract.

Issue 8: WHAT IF the Side Letter really does matter? Ok, assume that everything I’ve opined about in Issues 6 and 7 is completely wrong, what then? Does the “Side Letter” actually do what Schultz’s Complaint maintain that it does?

Discussion. Let’s compare statements made in Schultz’s Complaint with the actual text of the Side Letter:

| Schultz’s Complaint | Side Letter |

| 13. To ensure that defendant’s representations—which were critical to BCOS — were memorialized, Howard Schultz, who was Chairman of the BCOS Board of Directors, insisted that Clay Bennett, his counterpart in the Oklahoma City group, execute a side letter confirming the Oklahoma City group’s statements. The Oklahoma City group agreed, and in a letter dated July 18, 2006, on the stationary of defendant The Professional Basketball Club, LLC, Mr. Bennett wrote to Mr. Schultz that “it is our desire to have the Sonics and the Storm continue their existence in the Greater Seattle Area,” and specifically denied any “intention to move or relocate” the Sonics if the group could negotiate a lease arrangement. In fact, the Oklahoma City group did not desire to continue ownership of the Sonics in Seattle under any circumstances, even if it could negotiate a favorable lease. | We wish to confirm to you personally some of the key elements of the conversation we had with you yesterday. As discussed, we do not believe that KeyArena is designed to support the requirements of a viable NBA franchise, and thus achieving a modern successor venue and lease arrangement will be critical to the future success of the teams. In this regard, we would assume the mantle of the current ownership group in seeking to achieve this important next step. Moreover, it is our desire to have the Sonics and the Storm continue their existence in the Greater Seattle Area, and it is not our intention to move or relocate the teams so long, of course, as we are able to negotiate an attractive successor venue and lease arrangement. Our commitment to you to use our good faith best efforts over the coming year to negotiate such a venue and lease arrangement in the greater Seattle Area provides further concrete evidence of this intention. In addition, we will obviously assume all of BCOS’ obligations regarding the Key Arena Use Agreement at closing and intend to honor those obligations just as the current ownership group has done. ¶We are thrilled to have this opportunity, and would like to thank the entire Sonics and Storm organizations for making it a possibility. |

Only the most biased reader could conclude that Side Letter created an obligation on PBC to actually remain in the Seattle area beyond the express provisions of Contract ¶5.3. The letter’s expression is that “it is not our intention to move” … “so long, of course, as we are able to negotiate an attractive successor venue and lease arrangement.” To the extent that the Complaint interprets the letter’s provisions to create obligations beyond the initial year, it is difficult to find such statements in the letter — they don’t exist. In fact, the Side Letter may easily be construed to be more helpful to PBC’s side of the case than it is for PBOS’s since, implicit if not explicit in the letter is that the “non-intention” to move is conditioned upon obtaining an attractive successor venue to KeyArena and lease arrangement — i.e., that not happening, such an intention would no longer remain.

Issue 8: What about the damages? In each “Claim For Relief” section, the two respective Complaint sections conclude with a similar allegation: As to “Fraudulent Inducement:” “28. BCOS has been harmed by defendant’s intentional misrepresentations, omissions, and concealment”; as to “Negligent Representation:” “32. BCOS has been harmed by defendant’s negligent misrepresentations and omissions.” Apparently, “harmed” is another way of saying, “damaged.” The Complaint does not otherwise identify the alleged “harm” or “damage” to BCOS.

Discussion: Although this writer has no personal knowledge of Washington state law, if it is true, as Marc Edelman has written in this article that, among other things, damages must be alleged and proven as an essential element of the litigation, then proof of damage is an essential element of Schultz’s case. Presumably, the Complaint’s language about “harm to BCOS” was intended to fulfill that pleading requirement.

But, what about “proof” of damages – and that’s damage to BCOS, the real Plaintiff, and not to Howard Schultz who is acting through his solely owned LLC (Canarsie Holdings LLC) to maintain this action? By all accounts, PBC paid a premium to BCOS for the 2006 purchase of the Sonics & Storm — well above fair market value. It’s hard to see any damage to BCOS there.

But, what about damage to “reputation” — is that enough, and if so whose reputation must be damaged — BCOS, or is damage to Howard Schultz’s personal reputation sufficient, he being a part owner of BCOS?

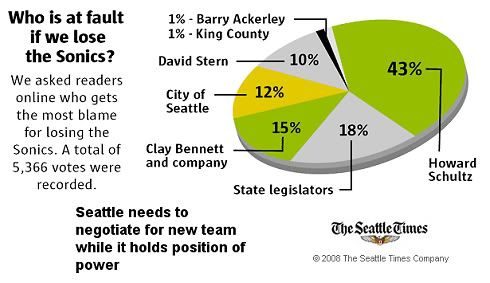

In this April 20, 2008, Seattle Times article, the results of an unofficial survey did show the following:

But, if this case is fundamentally tied to damage to Howard Schultz’s reputation … oh, come on … it was Howard Schultz who tried to rattle Washington’s chains about the Sonics moving well before the teams were sold to PBC! For example, see this February 1, 2006, article, a part of which reads,

SEATTLE (AP) – Seattle SuperSonics principal owner Howard Schultz said Wednesday he will look at all options – including moving or selling the team – if the state Legislature fails to earmark $200 million for the Sonics to refurbish KeyArena or build a new home.

Schultz, who talked to reporters before the Sonics’ game against the Golden State Warriors, said he’s told team president Wally Walker to look at all the alternatives.

One would be moving the Sonics to a market known to be interested in acquiring an NBA franchise, such as Las Vegas; Norfolk, Va., or Oklahoma City, or to one of three cities – Anaheim, Calif.; Kansas City, Mo., and San Jose, Calif. – that have made overtures to Sonics officials, the team said in a statement.

Schultz didn’t answer when asked whether he would still be involved in owning the team should it move to another city.

Also, see this April 14, 2006,Seattle Times article which, in part, reads,

By The Associated Press

NEW YORK — David Stern gave another warning that the Sonics could eventually leave Seattle, saying Thursday in a conference call that the city is “not interested in having the NBA there.”

Stern has said the Sonics’ lease with the city is the worst in the NBA, and he went to Seattle in February to ask Washington state lawmakers for tax money to renovate Key Arena.

Sonics owner Howard Schultz, the chairman of Starbucks Corp., has threatened to move or sell the team if state lawmakers don’t approve a sales-tax package to pay for a new or renovated arena. But state lawmakers last month said there would be no deal this year.

Also, see here and here. Enough, already!

This “damage” or “harm” part is just pure silliness, as best as I can tell.

Well, unless the spirit moves me, I think that I’ve said all I care to in this long article. Maybe I’m wrong 90% of the time — the Federal District Court sitting in Seattle will have the say about that — but, the problem for Schultz is, if only 10% of what I’ve said is “spot on,” that will probably be enough for the Schultz litigation to result in an unfavorable result, for him.

See you in the funny papers!

Related links:

- Marc Edelman’s observations

- A “legal” report from KING5.com

- Lester Munson of ESPN’s commentary

- Seattle P-I Article