Doug Dawgz note, irrelevant to this article but important that you know: Why only this single post during the month of January 2010? I’ve been very actively involved with several others in an as yet super-secret new, very serious, and ultra-exciting project related to Oklahoma City history. The wraps aren’t off on this new adventure yet but should be by Spring 2010. So, even though my January blog posts don’t show it, don’t think that I’ve not been busy with Oklahoma City history. Within two or three months or so, you will know what’s been going on and, if Oklahoma City history interests you, you will love it.

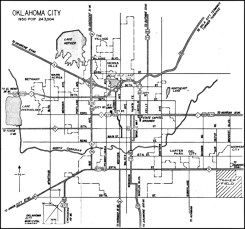

Before the hubbub surrounding the relocation of Oklahoma City’s I-40 Crosstown was hubbub of a much different type — whether, and, if so, where and when the city’s downtown would get an east-west crosstown expressway in the first place. At right, the Oklahoma City map from Oklahoma Department of Transportation’s 1955 highway map shows the Oklahoma City inset. You will find no existing or proposed routes of any express roadway through downtown. Click on the image for a larger view.

Before the hubbub surrounding the relocation of Oklahoma City’s I-40 Crosstown was hubbub of a much different type — whether, and, if so, where and when the city’s downtown would get an east-west crosstown expressway in the first place. At right, the Oklahoma City map from Oklahoma Department of Transportation’s 1955 highway map shows the Oklahoma City inset. You will find no existing or proposed routes of any express roadway through downtown. Click on the image for a larger view.

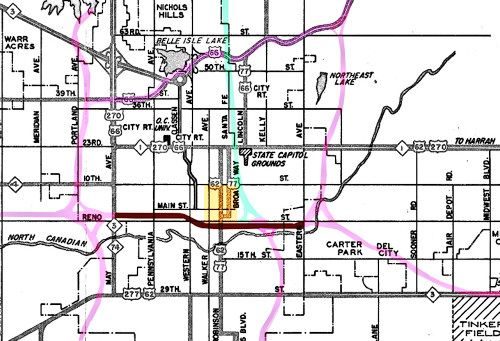

Marked up, the map roughly shows changes we know today …

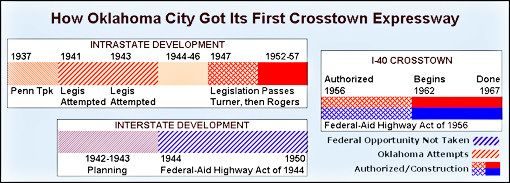

Although the primary focus of this article is the original I-40 Crosstown, a complete telling of that story requires an understanding of how limited access superhighways came to exist at intrastate and interstate levels in the country and how that all came to be meshed together prior to the original I-40 crosstown being built. The story covers 26 years, between and 1941 through 1967, and its telling meanders around a good bit in the telling. In the end, the pieces all converge with the establishment and construction of the original I-40 elevated crosstown flanking the south side of downtown Oklahoma City.

1940s in Oklahoma Toll Roads Dawn of Interstate System

Assessing the Needs Status in 1945 Who Needs Experts? Bartholomew Plan

An Opposition Plan Decision Plan Detail

BIRTH OF LIMITED ACCESS HIGHWAYS. A pair of significant events occurred in the late 1930s – early 1940s at both state and federal levels which proved to be harbingers of things to come. In Pennsylvania, the pioneer 160 mile Pennsylvania Turnpike was authorized by 1937 state legislation; at the federal level, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944 was adopted by Congress in December of that year.

The Pennsylvania Turnpike. Construction began in 1938 and the superhighway formally opened October 1, 1940. Skeptics claimed it was a boondoggle but actual usage proved them wrong. Planner’s original estimates were that 1.3 million vehicles would use the turnpike annually, but the early number proved to be 2.4 million. According to the Pennsylvania Turnpike’s website, the project’s inspiration was “Germany’s 100-mph autobahns, built to serve the needs of the users rather than controlled by the terrain.” Among many important features which could be mentioned here, only two will be in this passing summary: (1) the superhighway did not enter into cities along the route — instead, it closely by-passed them; and (2) the turnpike was a toll road to be paid for by the highway’s users. Neither feature was lost in legislation proposed for Oklahoma in the 1940s.

Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944. According to the Federal Department of Transportation’s website,

In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed a National Interregional Highway Committee, headed by Commissioner of Public Roads Thomas H. MacDonald, to evaluate the need for a national expressway system. The committee’s January 1944 report, Interregional Highways, supported a system of 33,900 miles, plus an additional 5,000 miles of auxiliary urban routes.

In the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944, the Congress acted on these recommendations. The act called for designation of a National System of Interstate Highways, to include up to 40,000 miles “… so located, as to connect by routes, direct as practical, the principal metropolitan areas, cities, and industrial centers, to serve the National Defense, and to connect at suitable points, routes of continental importance in the Dominion of Canada and the Republic of Mexico.”

In this federal program, the federal government would match, 50/50, money committed by a state and/or city to participate in the program except that cities were required to pay for 1/3 of the cost to acquire needed right-of-ways.

OKLAHOMA REACTION TO THESE DEVELOPMENTS. At the intrastate (Oklahoma only) level, after 6 years of trying, the Oklahoma Legislature approved the creation of the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority in 1947 and its initial project, the toll road between Oklahoma City and Tulsa. At the interstate level, the participation of Oklahoma City is more oblique, as you will see.

Intrastate Turnpikes. Not directly related to the federal legislation and with the Pennsylvania Turnpike serving as the example, legislative sessions in 1941, 1943 and 1947 attempted to authorize a toll-road between Oklahoma City and Tulsa and establish an entity, eventually named the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority, to accomplish that purpose. These attempts spanned the administrations of three governors. Governor Leon C. Phillips did not support the 1941 proposal and was reported to have said, dismissively, “It is not on my program.” By a vote of 21-18, the bill was killed in the Senate — the Senate author of that bill, Dr. Louis H. Ritzhaupt, Guthrie, has not been given appropriate credit for his laying the groundwork for this highway which would eventually be authorized in 1947. By 1943, Robert S. Kerr was Governor and, in his term, a similar proposal was before the Legislature, this one sponsored by the American Legion. According to Milt Phillips, the Legion’s adjutant general, the bill was one of a series of projects designed to provide jobs for returning soldiers. Whether Governor Kerr took a stand on this bill I’ve not determined with certainty but it does not appear that he did. Regardless, it did not pass.

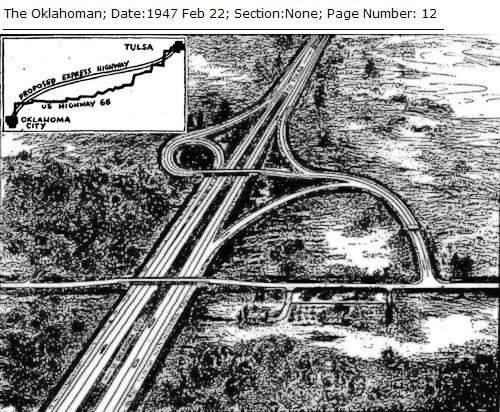

With the election of Roy J. Turner, Oklahoma’s Governor between 1947-1951, a reinvented toll road proposal gained the the chief executive’s qualified and, early on, non-public support. Even though the road would later bear his name, he was certainly not the originator of the proposal and only took a leadership roll toward the end of the legislative session. The proposal’s sponsors were the Oklahoma City and Tulsa Chambers of Commerce with leadership coming from members of the House and Senate. After proponents conferred with the governor before the bill was introduced in the Senate, he gave his qualified but quiet blessing. In its original form, the bill authorized the creation of the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority which would have the authority to construct the Oklahoma City – Tulsa toll road as well as other such roads in the future. The route between Oklahoma City and Tulsa was said to take an “airline” straight-line path (unlike the Pennsylvania Turnpike which included many sweeping curves). A drawing in the February 22, 1947, Daily Oklahoman gave a glimpse at what was being proposed:

Strong opposition came from business interests and legislators from cities along U.S. Highway 66 between the metropolitan cities, most notably Bristow, Sapulpa, Chandler, and Stroud. At a March 5 meeting of the newly formed Oklahoma branch of the U.S. 66 association, representatives from those cities were adamantly opposed but others not located between the metropolises such as Vinita and Miami were not. At the meeting, Oklahoma City’s chamber was represented by E.K. Gaylord, C.R. Anthony, J.S. Hargett, and Jack Hull. Tulsa’s chamber had its leaders present, as well.

Debate in the Senate was fierce. At the March 25 meeting of the roads and highways committee, opponents characterized the proposal as “unholy” and “ungodly” and one which burst upon cities like Sapulpa “like an atomoic bomb.” Fresh in memory were the actions of Germany when B.D. Erwin from Chandler said, “If Poland had a right to object to the pincer movement, Lincoln county has the right to raise the same objection to this.” Opposition was also expressed by Oklahoma Citian Sam Shelburne, principal owner of the Park-O-Tell motel immediately north of the State Capitol on Lincoln Boulevard. He said,

When dealing with this bunch of promoters you are not dealing with Harold Shimleys or Kellys, but you are dealing with the slickest promoters in the United States. They employed one fine law firm to represent them. Then they sold E.K. Gaylord clean up to the gills.

The reference to Shimley and Kelly was sort of a back-handed compliment — Harold Shimley is described at page 147 of the book Oklahoma Justice as being a small-time but ambitious local gambler, accumulating 25 arrests from Houston to Chicago. The “Kelly” being referenced was probably Patrick J. Kelly, a Chicago bootlegger who is also described in the same page of the book.

The efforts of the road’s opponents were not unrewarded — the Senate bill was amended to require that the road pass within one-half mile of the city limits of Sapulpa, Stroud, Bristow, and Chandler. I’m uncertain whether done in the Senate or House version, but only the Oklahoma City-Tulsa toll road was authorized, and no more. Even as amended, the vote carried the Senate by a single vote above majority even though more than a majority of senators were joint authors when the bill was first introduced.

After Senate approval, Governor Turner went public in his support of the proposal but conditioned upon the road’s proximity to cities along the route, full maintenance of U.S. 66, and that no state funds would be used in the toll road’s construction, among other things. By the time the House considered the Senate bill, amendments were made in committee and the bill was debated on the House floor. Over opponents objections that the bill would be an opening wedge for an entire system of toll roads in Oklahoma, the House bill carried easily by a vote of 77-32. Senate leadership accepted House changes without resorting to consideration by a conference committee and the House bill passed by a vote of 27-12, 5 votes more than a majority. On May 1, Governor Turner signed the bill which became effective 90 days later in August 1947. A threatened statewide referendum which would undo the legislation never came to pass, and the Turner Turnpike, the first such project west of the Mississippi River, opened in 1952.

The First Interstate System. This section explores some of what Oklahoma City did and did not do in the 1940s when offered the opportunity to participate in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944. A synopsis of the 1943-1950 period is this:

| Beginning at least by 1943, the federal government began anticipating major new highway construction upon the successful close of World War II. States were offered opportunities for input into that process as to what was needed, priorities, and estimated costs, and Oklahoma participated in that process. Among other things, the Act broadly authorized a new 40,000 mile superhighway (then a term frequently used to describe) interstate highway system. In those instances that a new highway would be located within a municipality, cities wishing to participate were required to submit proposals to their respective state agencies in the formulation of a statewide plan which, in turn, would be conveyed to the federal Public Roads Administration (PRA) for further evaluation, study, rejection, modification and/or approval. Cities were required to bear 1/3 of the cost of obtaining right-of-ways but other costs would be divided 50/50 between state and federal authorities, assuming that funding was available. Cities were also required to submit specific, even if tentative, models for their proposals. Whether because of a strong and persistent north/south division in the City Council, or lack of effective leadership, or disagreement about what the city’s share of right-of-way expense should be, or, for roads which would connect and fall within more than one city (e.g., the proposed new north/south connection between Oklahoma City and Norman), the absence of agreement between such cities, or just because the city did not have a sense of urgency in the matter and just sort of sat on its hands in failing to present proposals which matched the requirements, the federal opportunity which presented itself was not matched by action needed to be performed by the city. While a generous amount of professional and political study, discussion, debate, etc., was generated between 1944 and 1950, none of it produced the action needed for implementation of any new superhighways to be located within the city while that particular federal plan remained in place. As far as superhighways were concerned, all that Oklahoma City got in the process was a lesson about the effects of its own inaction, regardless of the reason. |

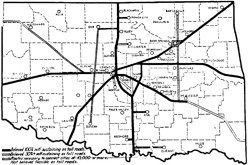

Post-war Needs. I’ll begin this period by noting that H.E. Bailey, former Oklahoma City Manager, assumed the post of chief engineer of the state highway department in February 1944. He would later become and was head of that department and/or the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority during most of the time relevant to this discussion. Upon his appointment, he said that he did not have any definite plans about the post-war Oklahoma highway construction — that modest notion would radically change by the time that he became director of the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority when, in November 1955, he made his sweeping proposal for a 1,227 mile system of Oklahoma toll roads, shown above. But, I’m getting ahead of myself.

Post-war Needs. I’ll begin this period by noting that H.E. Bailey, former Oklahoma City Manager, assumed the post of chief engineer of the state highway department in February 1944. He would later become and was head of that department and/or the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority during most of the time relevant to this discussion. Upon his appointment, he said that he did not have any definite plans about the post-war Oklahoma highway construction — that modest notion would radically change by the time that he became director of the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority when, in November 1955, he made his sweeping proposal for a 1,227 mile system of Oklahoma toll roads, shown above. But, I’m getting ahead of myself.

What were Oklahoma’s post-war needs? In March 1944, Bailey and Ben Childers, then chairman of the highway commission, estimated to the U.S. House Committee on Roads and the Senate Committee on Post Offices and post Roads that Oklahoma’s post-war needs were in the magnitude of $210 million. That figure, though, was qualified. According to a March 9, 1944, Oklahoman article, that number was based upon projects “designated to the present standard. If the proposed standards of the inter-regional system are adopted, the total will be increased by approximately $20,000,000.” The article noted that, “It is explained that the $210,000,000 doesn’t include a direct airline route between Oklahoma City and Tulsa, but if the proposed standards are adopted the plan would call for the airline.” As previously discussed, “airline” was a term used for point-to-point straight-line highways, i.e., as the crow flies. The article concludes, “Commission members said they hope to see a road construction program of at least $100,000,000 start immediately after the war.” No superhighway which cut into Oklahoma City’s limits was mentioned in the report. In December 1944, the federal act passed Congress and a December 17, 1944, Oklahoman article reported that,”A three-year post-war highway construction program calling for expenditures of $54,013,000 in Oklahoma will be provided under the bill past in its final form last week and made ready for the signature of President Roosevelt.” The article notes Bailey as saying that the allocation for cities was far below what had been anticipated and that it would not permit “the state to carry out the planned construction in routing highways through cities.” The article added,

A provision is made in the bill for national system of interstate highways not exceeding 40,000 miles in total. The route shall be designated to connect the principal metropolitan areas, cities and industrial centers to serve the national defense and connect at suitable border points with routes of continental importance in the Dominion of Canada and the republic of Mexico. No appropriation is provided, and it was interpreted as a policy statement looking to the inter-regional highway system.

Status In 1945. In formulating a plan which involved the same road entering two cities, cooperation was called for. A September 29, 1945, Oklahoman article reported that, “Oklahoma City and Norman are taking a chance on losing out on the four-lane highway in the 1946 construction program by failing to designate the control points.” “H.E. Bailey, state highway engineer, said neither the officials of Norman nor Oklahoma City have given the highway department a report on the requests for preference on the point of entrance of the proposed new highway.” The article notes that the cities had not given definition as to the “control point” that the proposed highway would enter the respective cities, and, quoting Bailey, said, “We have to know the locations before we can prepare the plans for the road.”

Otherwise, 1945 failed to produce results. By October, the city had “shelved plans for links with inter-regional roads.” In an October 5, 1945, Oklahoman article, it was reported that,

Plans to link Oklahoma City into the proposed national inter-regional highway system were shelved Thursday at a special city council session.

The action instituted a successful block wedged by a group of Capitol Hill business men and merchants augmented by scattered northeast interest groups.

* * *

Kick-off of the meeting was a speech by Mayor Hefner, urging expedient action without entering into personalities or regard to selfish interests.

Sam Shelburne, owner of the Park-O-Tell immediately north of the State Capitol on Lincoln Boulevard (and recall that Shelburne also opposed the 1947 Oklahoma City – Tulsa toll road legislation) had emerged as a leader of the opposition. He opposed the concept of a superhighway entering the city at all and instead maintained that such highways should stop at certain control points along the city limits and, from those points, traffic should be allowed to sift through the city as it then did. According to the article, he also “asserted that the city’s primary interest was that portion of the super road which bisected the city and that the city was extending further than its official scope in suggesting roads lying outside corporate limits.” As for a new east/west highway passing by/through/near downtown, a “288-foot road through the commercial area,” the article reports that Shelburne said that it would be a definite barrier between the north and south sides of the city.” The article reads, “[Shelburne] Charging that the action committee’s recommendations were ‘greased,’ he maintained that there had been ‘no public hearing or open meetings and the public hasn’t had an opportunity to express itself.'” The article closes by noting, “Allen Street, ward 1, moved that the state engineer be advised that the city was willing to co-operate with the state and government but that as yet no plan could be agreed upon. It carried unanimously.”

Three conferences were held few days later in an attempt to defuse acrimony and find a consensus. Meeting with south side business interests, Bartholomew acted as consultant and mediator and, judging by an October 9 Oklahoman article, progress had occurred. The article reported that, “[A] majority of a group of southside business men favored the action committee’s recommendations on the main express roadway, supplemented by an urban feeder artery, which would run through Capitol Hill’s main street,” and the article reported that Bartholomew indicated that such a feeder road was a possibility under the federal scheme. He also noted that the limited access highway could not be constructed at grade level but must be either up or down from it and said, according to the article, “the federal bureau of public roads had established a policy of having the major routes project through the center of the cities,” and that surveys showed that 72% of traffic stops in the downtown area. The article concluded,

If the two groups get together on a plan Thursday night, it will no doubt pass the council the following Tuesday and be presented to the state highway commission immediately.

As you will see in the following section, that optimism proved to be unfounded.

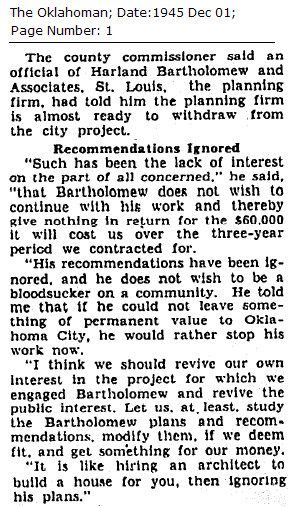

Experts, Experts, Who Needs Any Experts? Throughout this process, Oklahoma City engaged the services of respected experts to assist and advise regarding its street and highway needs and possibilities, primarily Harland Bartholomew and George W. Barton. Barton, professor of traffic engineering at Northwestern University, advised the city for at least 12 years, into the 1950s, however his duties and influence in the 1940s were more associated with local streets and roads. Bartholomew & Associates, a prestigious St. Louis city planning and landscape architecture group, more prominently assisted the city in responding to the 1940s superhighway planning. After the Bartholomew Plan was adopted by the city in 1946, Bartholomew’s work was done but the state highway department and federal public roads administration engaged Guy B. Treat, a local engineer, to serve as a consultant to assist in the implementation of the Oklahoma City urban roads activity. In several of the articles linked below, you will observe references to the Bartholomew, Barton, and/or Treat reports/proposals, and this note gives a brief introduction about those experts and their opinions. At this point in time, the expert was Bartholomew. Despite his best efforts in presumably giving objective opinions and advice which matched federal requirements, his views initially proved to be a lesser force and influence than were City Council northside/southside issues and/or the cost associated with acquiring right-of-way for a superhighway’s presence within the city’s boundaries, or whether it would even be desirable to have an east/west superhighway pass near or through downtown. The frustration was vividly illustrated by a December 1, 1945, Oklahoman article in which county commissioner Mike Donnelly expressed his own frustrations. A snippet from the article is shown above right. After his speech, the article concludes,

Experts, Experts, Who Needs Any Experts? Throughout this process, Oklahoma City engaged the services of respected experts to assist and advise regarding its street and highway needs and possibilities, primarily Harland Bartholomew and George W. Barton. Barton, professor of traffic engineering at Northwestern University, advised the city for at least 12 years, into the 1950s, however his duties and influence in the 1940s were more associated with local streets and roads. Bartholomew & Associates, a prestigious St. Louis city planning and landscape architecture group, more prominently assisted the city in responding to the 1940s superhighway planning. After the Bartholomew Plan was adopted by the city in 1946, Bartholomew’s work was done but the state highway department and federal public roads administration engaged Guy B. Treat, a local engineer, to serve as a consultant to assist in the implementation of the Oklahoma City urban roads activity. In several of the articles linked below, you will observe references to the Bartholomew, Barton, and/or Treat reports/proposals, and this note gives a brief introduction about those experts and their opinions. At this point in time, the expert was Bartholomew. Despite his best efforts in presumably giving objective opinions and advice which matched federal requirements, his views initially proved to be a lesser force and influence than were City Council northside/southside issues and/or the cost associated with acquiring right-of-way for a superhighway’s presence within the city’s boundaries, or whether it would even be desirable to have an east/west superhighway pass near or through downtown. The frustration was vividly illustrated by a December 1, 1945, Oklahoman article in which county commissioner Mike Donnelly expressed his own frustrations. A snippet from the article is shown above right. After his speech, the article concludes,

After some discussion, the commissions decided to put the Bartholomew matter first on its agenda and, following further study of the situation, to enlist the aid of the Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce and public-spirited citizens in reviving interest in the project.

The inter-regional highways are the new cross-continent super-roads. Under present U.S. road plans, a north-south and east-west express highways would intersect at Oklahoma City.

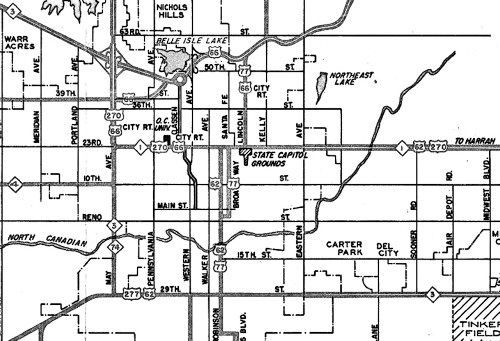

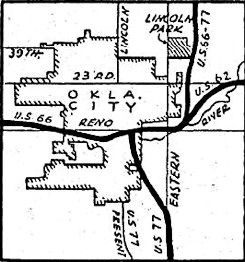

Bartholomew Plan Overview. The debate’s real focus was whether the city would have a superhighway which would pierce and run through the city’s limits which is precisely what the Bartholomew plan did, as seen at the right, and the plan is not at all unlike the system we know today. It is recalled that until the present day I-40 Crosstown was constructed no east/west highway passed through or near the downtown area. From downtown, to get to Yukon, State Highway 4 ran west along N.W. 10th Street; for El Reno, N.W. 39th Street, U.S. 66 (among other numbers) was the route; eastbound traffic to Shawnee would use S.E. 29th Street, State Highway 3, or N.E. 23rd Street, U.S. 270. Moreover, no express north/south routes were available. While U.S. highway traffic did flow north and south through downtown, it was via slow moving local streets.

Bartholomew Plan Overview. The debate’s real focus was whether the city would have a superhighway which would pierce and run through the city’s limits which is precisely what the Bartholomew plan did, as seen at the right, and the plan is not at all unlike the system we know today. It is recalled that until the present day I-40 Crosstown was constructed no east/west highway passed through or near the downtown area. From downtown, to get to Yukon, State Highway 4 ran west along N.W. 10th Street; for El Reno, N.W. 39th Street, U.S. 66 (among other numbers) was the route; eastbound traffic to Shawnee would use S.E. 29th Street, State Highway 3, or N.E. 23rd Street, U.S. 270. Moreover, no express north/south routes were available. While U.S. highway traffic did flow north and south through downtown, it was via slow moving local streets.

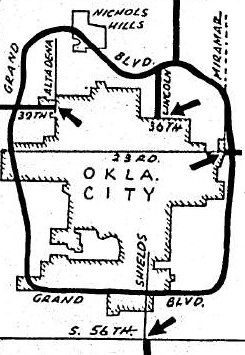

An Opposition Plan. Seen at right, the differences between the Bartholomew Plan and the opponents’ so-called compromise plan are night and day. This plan was hurriedly conceived and put together by opponents during an April 26 city council meeting. Grand Boulevard would become a paved but not a super highway, a loop, from which other new federal highways would connect at city limits and proceed outward in four directions, and none of those roads would even come near downtown. It was argued that an east-west superhighway would do nothing more than effectively re-create barriers, the Rock Island and Frisco rail tracks, it had taken the city so long and at great expense to remove only 15-16 years earlier, and that such a superhighway would further divide north and south Oklahoma City.

An Opposition Plan. Seen at right, the differences between the Bartholomew Plan and the opponents’ so-called compromise plan are night and day. This plan was hurriedly conceived and put together by opponents during an April 26 city council meeting. Grand Boulevard would become a paved but not a super highway, a loop, from which other new federal highways would connect at city limits and proceed outward in four directions, and none of those roads would even come near downtown. It was argued that an east-west superhighway would do nothing more than effectively re-create barriers, the Rock Island and Frisco rail tracks, it had taken the city so long and at great expense to remove only 15-16 years earlier, and that such a superhighway would further divide north and south Oklahoma City.

Decision. Finally, in late April 1946, it appeared that the City Council was about to make its decision. At least, an April 24 Oklahoman article so predicted:

City council members set the stage Tuesday for another major street plan row at 9 a.m. Friday when they expect to decide whether they will submit the Harland Bartholomew inter-regional highway plan to the state highway department as a basis for applying for federal aid construction money.

The council has been divided on the question since the plan was first drafted. Several minor changes have been made but at least two members, G.A. Stark, ward four, and Victor Sellers, ward three, indicated they will fight submission of the plan in its present form.

Hal Whitten, chairman of the regional planning commission, told council members that the submission of a plan did not commit the city to that plan. What was important, he said, was that some plan be submitted in the first place. He said,

“The federal government will not initiate these superhighways with the city. Oklahoma City must file a suggested plan, which is what this is. The federal engineers then will review it, and make whatever changes they see fit. Before it can be adopted as a final plan, it must come back to the council several times. After all changes are made, the city still has the absolute power to block it simply by refusing to appropriate the one-third of right of way cost as its share of participation.”

But, when that four-hour eventful meeting occurred, what did the city decide to do? Despite the advice of C. Edgar VanCleef, planning commission member, that the superhighway,

“[T]o meet federal specifications, must go near the heart of the city, where traffic can feather out to the packing houses, the hotel area, Capitol Hill and the residential sections,”

the council ducked the dispute by sending both plans to the state highway department, effectively saying, “Take your pick!” The opposition was ecstatic. Read all about it in the April 27 Daily Oklahoman.

The council would not get off the hook that easily. The highway department effectively rejected the city’s decision by notifying the city that no action would be taken until a single route, acceptable to the city, was submitted, and a brief May 21 Oklahoman article reported that the matter would be back on council’s docket the next day. On May 22, and without fanfare in the press, the city council unanimously approved the plan recommended by its planning commission, the slightly modified Bartholomew plan.

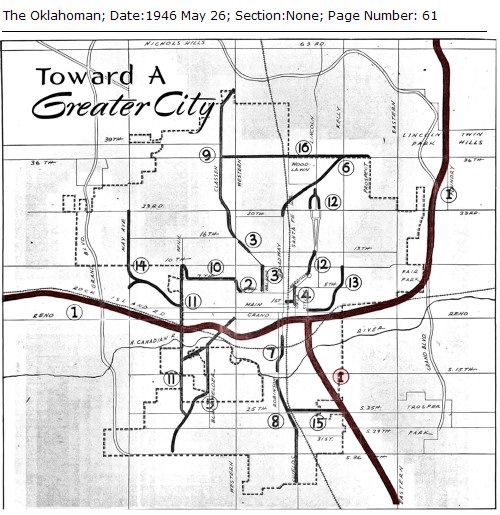

Bartholomew Plan Detail. Finally, on May 26, the Oklahoman could report that the city council had taken a position, even if it may have emerged through the back door and somewhat stealthily. Here’s the detail — click on the image for a better view.

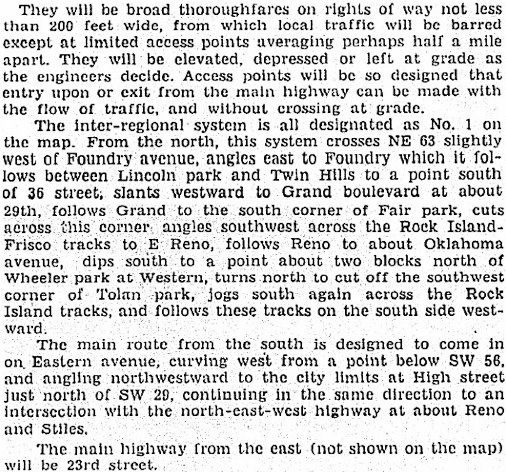

The dark red inter-regional superhighways were previously seen above, but the overall plan shown above includes a “priority list” of 15 additional items recommended for early action. Click here to read the full list. As for details about the superhighway itself, the article gives this description:

… more later today …